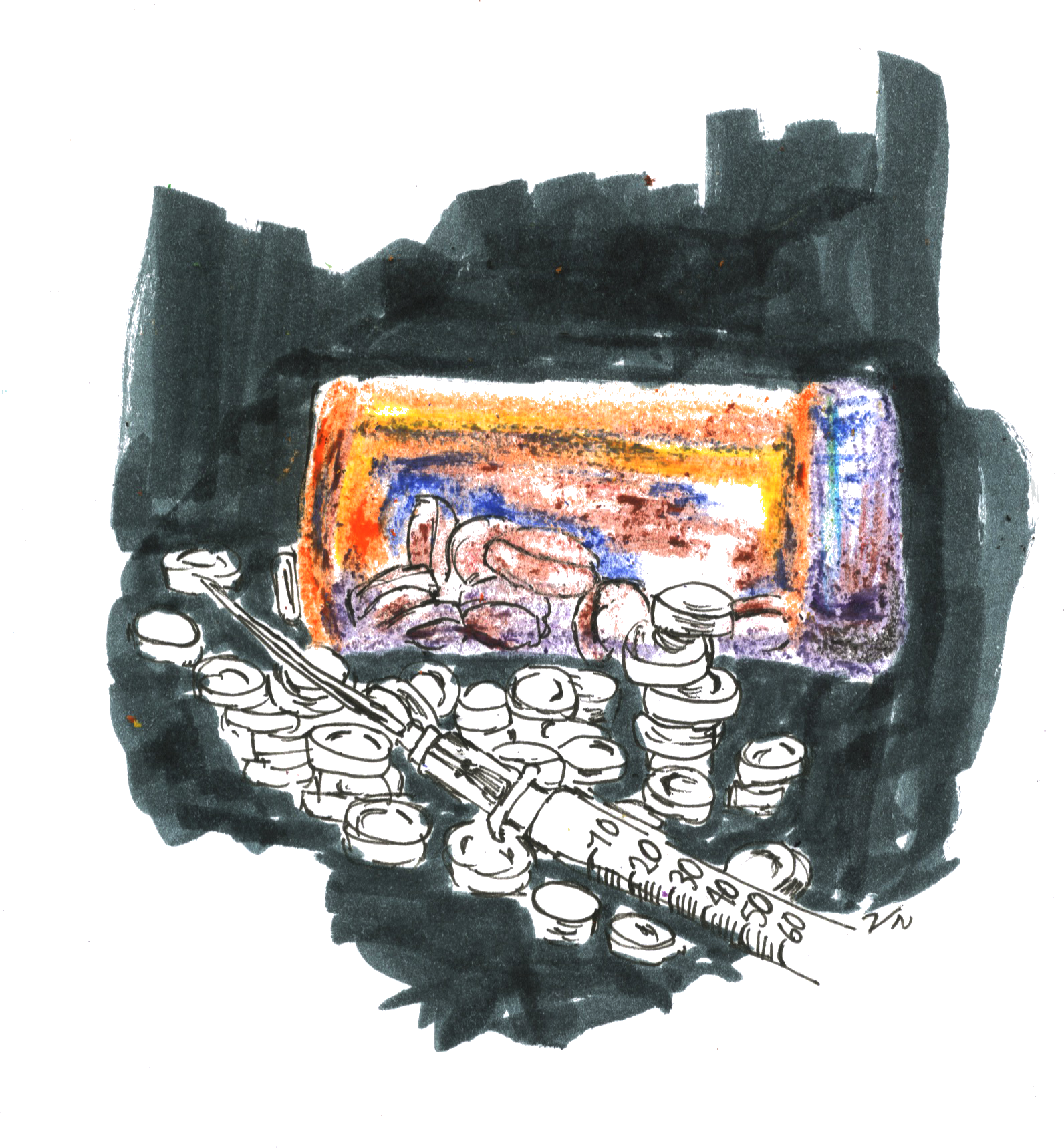

The U.S. has faced an opioid overdose crisis for nearly 30 years, and both policymakers and scientists have been working to develop solutions to the drug epidemic. But even with some success, the effectiveness of treatment interventions offered to opioid overdose patients is still unclear.

Prompted by these issues, a group of researchers from the Yale School of Medicine and Brown University’s Alpert School of Medicine set out to understand the effectiveness of current interventions used to curb opioid overdoses. In a study published on Aug. 1 in the Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, the researchers found that patient access to both opioid-blocking drugs and peer support groups improved patient health outcomes.

“We need a multipronged strategy to address the epidemic,” said Elizabeth Samuels, first author of the study and former postdoctoral fellow at the School of Medicine. “There is not one solution that is going to really address the crisis. Multifaceted, multidisciplinary, multistakeholder investment and involvement are crucial — and not just in the health care setting, but also in ones that address social determinants of health, if we’re going to be successful in reducing overdose rates.”

In the late 1990s, U.S. health care providers began to rapidly prescribe opioids to patients for pain relief, under assurance from pharmaceutical companies that patients would not develop addictions to these medications. But these drugs also cause euphoria, potentially leading to abuse, according to the National Institutes of Health website.

An opioid overdose can cause a patient to stop breathing — leading to unconsciousness, coma or even death. Naloxone, an opioid-blocking drug, can be used to reverse the effects of opioids and can rapidly restore breathing, according to the NIH.

The study analyzed the health outcomes of patients who, following an overdose, were given access to their own supply of naloxone or given naloxone in addition to a peer recovery coach, a person who previously struggled with addiction and has been trained to help current patients. These two groups tended to initiate addiction treatments sooner, made fewer overdose hospital visits and had a lower mortality rate, compared to those who did not receive these interventions.

But Samuels and co-author of the study, Brandon Marshall, said this was only a preliminary analysis, and they need to increase their sample size in order to better understand their results.

Some scientists have voiced concerns about take-home naloxone, arguing that it may promote further drug use and lead to increased overdose deaths, according to Samuels.

The study, however, refuted these doubts. Patients who were given their own supply of naloxone were not more likely to die from an overdose, according to their results.

In October, the authors will launch a larger study to further examine the effects of peer recovery coaches on patient outcomes.

Marshall said that Rhode Island was the first state to offer a peer recovery coach program.

“There are a lot of other states that are interested now,” he said. “And I think that just underscores the need for strong evidence to support this approach, given so much interest in this type of program and resources being poured into peer recovery–based support services throughout the nation.”

The study’s patient population was based in Rhode Island, though Samuels said that Connecticut also faces the same issues when it comes to opioid overdoses.

In fact, to help prevent opioid overdoses in New Haven, the Yale School of Public Health held a public naloxone training session in September, which taught Yale and New Haven community members how to administer intranasal naloxone to someone who had overdosed.

The decadeslong crisis is not just a result of opioids that doctors prescribe. The epidemic has been exacerbated by street dealers who illegally sell opioids such as heroin and morphine on the street.

Additionally, street dealers may lace their opioids with substances like fentanyl — a synthetic opioid and elephant tranquilizer that is 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine. Most overdose deaths are now related to fentanyl ingestion, according to Marshall.

“It’s responsible for more than 60 percent of the [opioid overdose] deaths at this point,” he said.

More than 115 people die each day from an opioid overdose in the U.S., according to the NIH.

Marisa Peryer | marisa.peryer@yale.edu .