Yale Daily News

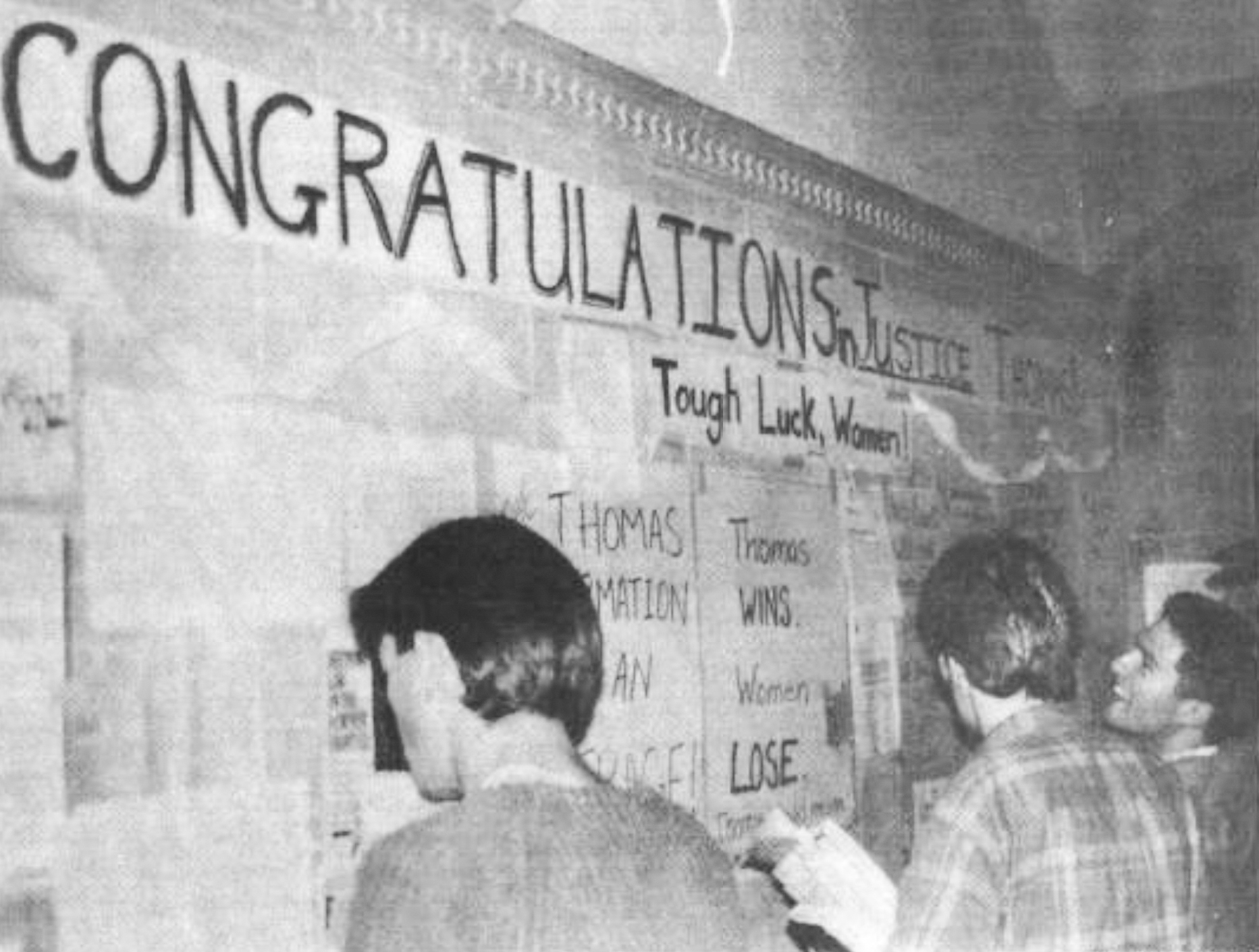

In 1991, Yale Law School students covered the walls of the Sterling Law Building with impassioned banners, clippings and written messages. Some signs read “Thomas Wins, Women Lose” and “The Supreme Court 1991 … Mediocrity and Misogyny,” while others read “Tough Luck, Women!” and “Congratulations Justice Thomas!”

Over the weekend — almost three decades later — the walls of the Law School were again flooded with signs condemning the potential confirmation of a Supreme Court nominee accused of sexual misconduct. Students had plastered signs along the hallways of the Sterling Law Building and displayed posters across the courtyard, with messages including “#StopKavanaugh” and “#IBelieveChristine” and “#IStillBelieveAnitaHill.”

Almost exactly 27 years separate the Supreme Court confirmation hearings of Justice Clarence Thomas LAW ’74 and Judge Brett Kavanaugh ’87 LAW ’90. But the allegations of sexual misconduct against Kavanaugh have rattled the Law School in much the same way that Anita Hill LAW ’80’s allegations against Thomas did in 1991.

Recent accusations by Christine Blasey Ford and Deborah Ramirez ’87 against Kavanaugh have prompted protests among Yale community members, much like those that arose after Hill came forward with allegations of sexual harassment against Thomas in 1991. While the testimony of Hill had little ultimate impact on Thomas’ confirmation, the allegations against Kavanaugh come in the wake of the #MeToo movement, which has brought down dozens of prominent men accused of sexual misconduct.

Now, students and faculty at the Yale Law School are calling for accountability from the Senate and the law school alike.

In recent days, Yale students have protested what they perceive as a rushed confirmation process for Kavanaugh. Over 400 Yale Law students, faculty members and undergraduates participated in a sit-in on Monday to protest Kavanaugh and stand in solidarity with Ford and Ramirez.

Yale undergraduates have planned a rally for Wednesday starting on Old Campus, standing in solidarity with survivors to call attention to sexual misconduct at Yale in light of allegations from Ford and Ramirez. Ramirez was allegedly assaulted by the Supreme Court nominee in Lawrance Hall, a dorm on Old Campus.

On Oct. 6, 1991, two days before Thomas’ final confirmation vote was scheduled to take place, the press reported that Hill had made allegations of sexual harassment by Thomas, for whom she had worked at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

Days after the allegation was made public, 120 female law professors — including Law School professor Judith Resnik, who signed a petition calling for an investigation into allegations against Kavanaugh decades later — signed a letter to the Senate Judiciary Committee, calling for a full inquiry into Hill’s account.

Protests at Yale continued even after Thomas’ confirmation, which occurred four days after Hill’s testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee.

On Oct. 17, 1991, two days after Thomas’ confirmation, students from Yale Law School Women, the Collective of Women of Color and the Law, the Women’s Committee of Law and Liberation and the Yale Journal of Law held a press conference, urging Thomas to resign and voicing support for Hill.

The students said Hill was unjustly degraded during the Senate hearings and argued that with Thomas on the bench, they could not trust the Supreme Court to protect women’s rights — an argument that opponents of Kavanaugh have also made in recent months even before sexual misconduct allegations against him became public.

Rachel Goldstein ’92, who attended Yale during Thomas’ confirmation hearings, said that most students she knew on campus agreed that the Senate should have taken Hill’s allegations more seriously.

However, not all students rallied around Hill in 1991. One student wrote in an op-ed for the News on Oct. 21, 1991, that the Senate had a duty to “give some presumption of innocence to the accused.” After Thomas’ confirmation vote, some law students also put up signs in the law building congratulating the newly confirmed justice.

Still, on Oct. 23 of that year, 15 students gathered at a forum sponsored by the Women’s Studies department to “[voice] anger over the mistreatment of [Hill] by the Senate Judiciary Committee” and “[promise] that senators who voted to confirm Thomas [would] pay a political price come election time,” according to a Yale Daily News article published the next day.

The article added that because the participants of the forum “knew they could do nothing to prevent [Thomas] from becoming an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court next Monday,” the group “used the forum to hash out issues that remained after the vote.”

According to the article, School of Medicine professor Linda Bartoshuk said at the meeting that the hearings illustrated how few people — including the senators on the judiciary committee — knew what sexual harassment meant.

“It’s amazing how many people don’t know what the law [on sexual harassment] is and what we tolerate,” Bartoshuk said at the forum.

But unlike Thomas, allegations against Kavanaugh emerge in the height of the #MeToo movement, which began when allegations against Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein in October 2017 thrust the issue of sexual assault and harassment into the public eye.

While Thomas was in his 30s when he allegedly harassed Hill, Kavanaugh’s accusers have said that the judge was 17 and 18 years old at the times of the alleged sexual misconduct, which occurred more than three decades before President Donald Trump nominated him to the nation’s highest court.

According to Goldstein, the #MeToo movement has made people “more emboldened to come out” with allegations. Goldstein added that while unwanted sexual advances by male students were not uncommon during her time at Yale, students rarely reported these incidents to the Yale administration.

“The hope is that in today’s environment something would be done [about the allegations],” Goldstein said.

Iva Velickovic ’14 LAW ’19, who helped organize the rally on Monday, added that the #MeToo movement has increased the awareness on “the seriousness of sexual misconduct.” With more people outraged by the allegations facing the Supreme Court nominees, law school students were more “efficient and organized” in supporting Kavanaugh’s accusers and protesting Kavanaugh’s confirmation, Velickovic explained.

On Friday, 50 Yale Law faculty members signed an open letter addressed to the Senate Judiciary Committee calling for an impartial investigation into the allegations against Kavanaugh and a “fair and deliberate confirmation process.”

And while only 15 students and faculty members participated in the forum following Thomas’ confirmation, over 2,200 Yale women have signed an open letter expressing support for Ford and Ramirez between Sunday — when Ramirez’s allegations became public — and Tuesday evening.

On Tuesday afternoon, University President Peter Salovey sent an email to students regarding Yale’s commitment to preventing and addressing sexual misconduct. While the email did not mention Kavanaugh, Salovey emphasized that sexual misconduct “has no place on this or any other campus.”

Salovey did not respond to a request for comment.

In Yale Daily News issues from Oct. 6 to 31, 1991, there was no mention of the University making an official statement regarding sexual misconduct or the allegation against Thomas.

Kavanaugh and Ford are expected to testify before the Senate on Thursday.

Alice Park | alice.park@yale.edu

Serena Cho | serena.cho@yale.edu