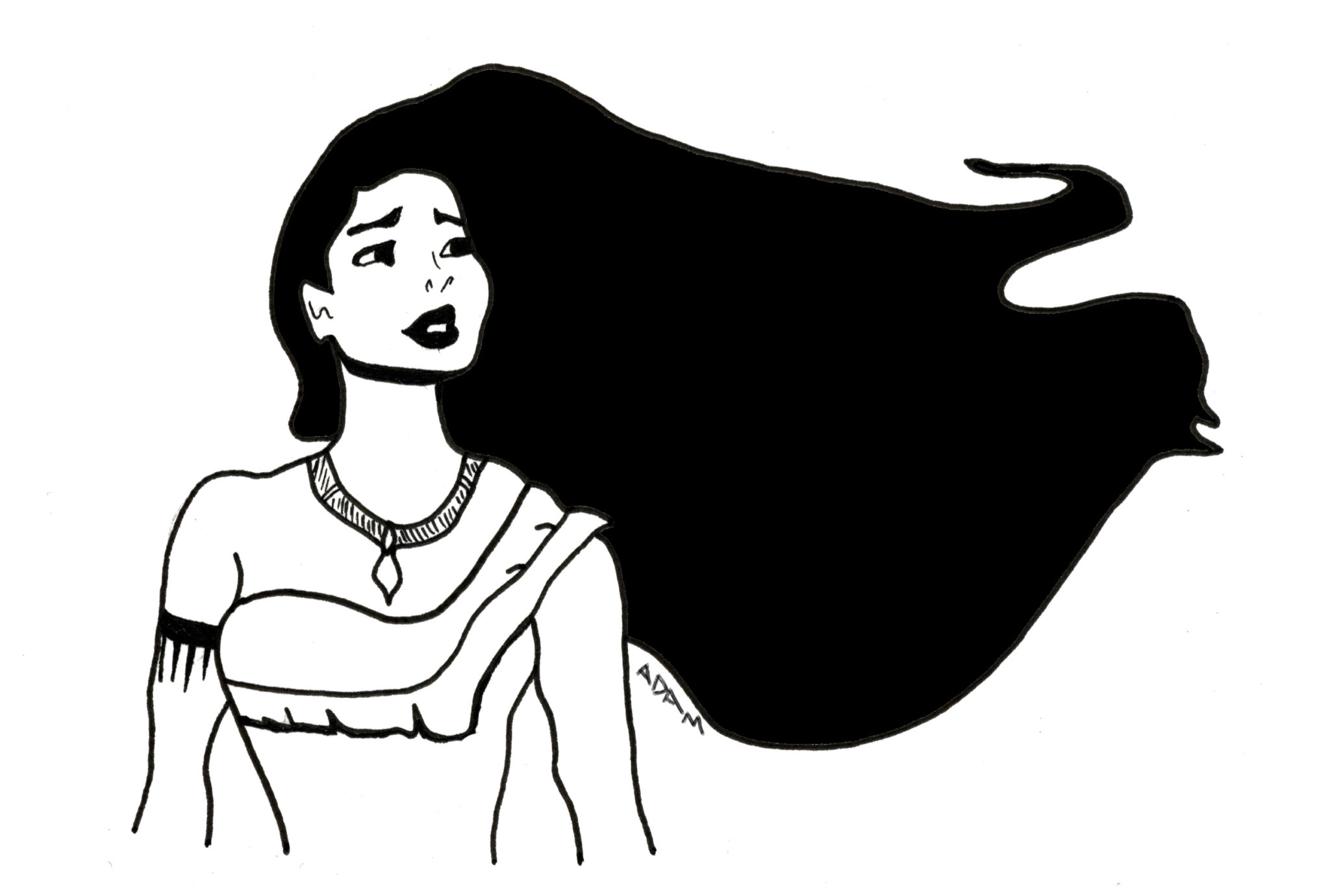

As a young Chinese-American girl, my favorite Disney princess was the one I identified most strongly with — Pocahontas. She was the only one who had long black hair like mine. In those early years, I eagerly watched the “Pocahontas” movies on loop, twirled with my Pocahontas-edition Barbie to the tune of “Colors of the Wind,” and begged my parents to purchase the Little Mermaid’s Prince Eric doll to keep her company. He was, after all, the only Disney prince with black hair.

Eventually, I discovered Mulan … I’ll leave my childhood excitement up to your imagination.

It was entirely impossible for five-year old me to imagine a day when I would sit in a movie theater watching “Crazy Rich Asians” with people of all colors or return home to soak in “To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before” on Netflix. But as we venture into a period of increasingly diverse media representation, the word “representation” is beginning to be thrown around carelessly. It is in danger of becoming a simple buzzword, an undeniable reason behind why we should elevate people of color into the hallowed halls of Hollywood. It, then, simultaneously becomes easy to reject.

As the issue of representation steps into the public eye and onto campus, similar to how sexual assault and rape have already, it slowly becomes more of a concept than a human experience. Sexual assault and rape became a hot topic over the course of the last year — in classrooms, in newspapers and in living rooms — and as such, began to belong less and less to those who had lived it, who were victims of its reality. These concepts lost their human element until they became a word to be thrown around, divorced from the plethora of shared experiences and sorrow that had brought them to light in the first place.

Those of us who discuss social issues like representation and rape need to alter the way we approach advocacy. It is easy for people to deny concepts. It is less easy for them to deny the lived truth behind the five-year-old Chinese girl who mistakenly identifies with Pocahontas or the victim who writes an anonymous account of their sexual assault at Delta Kappa Epsilon. Movements like #MeToo and personal stories on why representation matters expose how issues like sexism and racism manifest themselves in various facets of life. Discovering that your friends and classmates have been touched by these issues transforms them — it makes them untouchable, undeniable, real.

When I was eight, my godmother took me to the American Girl store to pick out a doll for my birthday. I knew that I wanted a doll with long hair like mine, so that I could braid it and style it in updos. After scouring the whole store, the only doll I could find that had my almond eyes was Ivy Ling, the sidekick to a Caucasian girl named Julie Albright. She had shoulder-length hair, so short that it couldn’t be tied up in a ponytail — but I chose her regardless. As a child, I had never heard the word “representation.” But even then, I wished that Ivy had her own story, that she could be more than a sidekick — so that I could too.

Representation is the ability for the next generation of people of color to be able to choose who they want to be. It is the idea that they can be bookish like Belle or talented like Ariel without being boxed into the identity of the sole character that looks like them.

So as we continue in our discussions of representation and social issues at-large on campus, let us elevate the lived stories of those for whom these “issues” are day-to-day life. To me, representation is more than just a two-dimensional concept. It is Pocahontas, it is Mulan and it is Ivy Ling.

Katherine Hu is a sophomore in Ezra Stiles College. Her column runs on alternate Wednesdays. Contact her at katherine.hu@yale.edu .