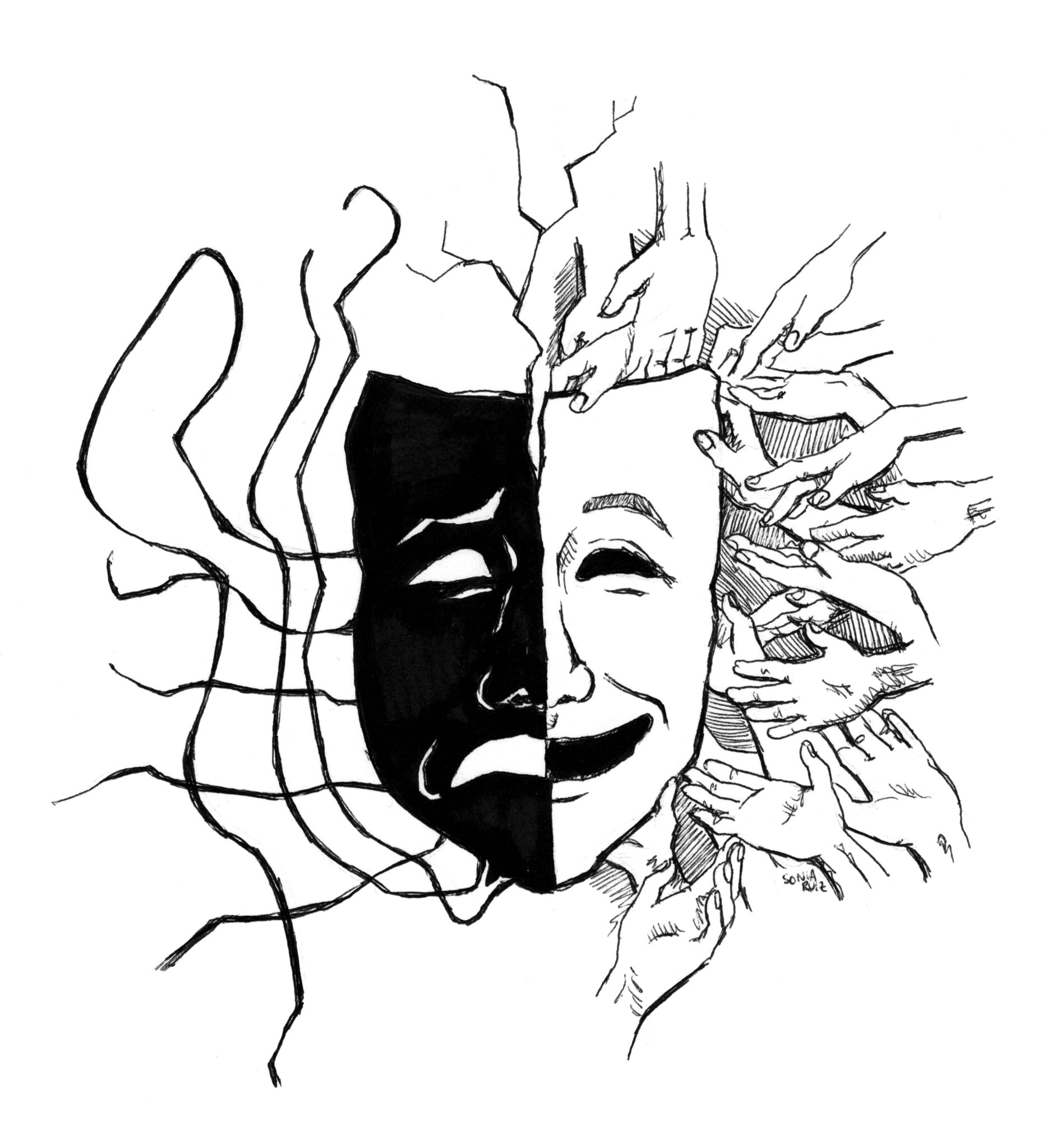

It is fitting to begin my final column for the News in the same way I have begun so many before: with an aphorism from my grandmother. The best thing about someone, she’ll often say, is the flip side of the worst thing said about them. If they’re absentminded, perhaps they’re delightfully dreamy. If they’re unwilling to argue, perhaps they’re a rock for their friends. If they’re critical, perhaps they’re also incisively perceptive. The most beautiful part of someone’s character is also the ugliest. That Janus-faced personality schism is what makes us ourselves.

At Yale, we condemn each other as “performative.” It’s one of our most common campus insults. I perform. She performs. That’s performative. Calling someone “performative” is akin to calling them “inauthentic,” claiming that they have no internal motivation. In a time when we are supposed to be investigating and developing ourselves, “performative” is a crime of disingenuousness.

Following my grandmother’s theory, “performative” must be the flip side of the strongest part of Yale. I think — I hope — that the beauty behind “performative” is a beauty in Yale’s collective. You cannot be performative if you do not have an audience who cares enough to spectate. And what is that, then, other than a “community”?

Our communal performance is also a communal audienceship, one that fosters some of the best and the most ubiquitous parts of Yale. To build community, we listen to each other’s life stories in pre-orientation programs, clubs and senior societies. We watch Cross Campus balloon and empty, balloon and empty again. We pay attention to our friends’ motivations and engage with their explorations. We do not carve out space to live in isolation here. Instead, we etch ourselves onto each other, an imprinting that creates an interested audience — and, thus, a community.

Only now, staring down the chute at graduation, am I beginning to understand how Yale’s community has changed my worldview. Over break, I found old journals and was surprised by how different my goals are now from when I started college. My goals were classes and career, an academic and intellectual approach to the future befitting an 18-year-old nerd. Of course, I absolutely wanted friendships from college but was more excited to feel as though my mind would be pulled apart in seminars. I thought of college as primarily a place for thinking, expecting friendships to come afterward.

In graduating now, these goals are almost unrecognizable. Of course, I aim to be excited and effective in my career. But career goals are now just some among many. Now, I know I will also work to have a strong and sturdy group of friends, people I call often to check in and check up. I want something resembling a weekly meal, a ritual over food to develop a community over time. I want to love someone well and to one day love our children well, too. My career aspirations now stand next to my desire for a concrete and visible community.

This, to me, is the most obvious effect of Yale on my life, and I think I am in good company with the class of 2018. Yale is both womblike and claustrophobic, a community both nurturing and exhausting. Losing an established community is the most obvious rupture between the past and the future that starts in just a few weeks, when we launch our caps into the air. Here, we have roommates who are familiar with our pattern of time. Here, we have adults who care about us unraveling and retying our thoughts together, adults who help us make better versions of ourselves. Here, we have a shared reality in a way we won’t ever again. But we will carry the memory of what a community feels like into our future. We will know that we can one day make that again.

The task of these next few months — these next few years, really — will be to decompress from our Yale performance before we build and rebuild a new community. Living without a caring audience will be a useful readjustment and a useful return to lives that exist out of view from Yale. Once we’ve ironed out the worst of our performative selves and have learned how to live without an audience, we’ll be ready to come back to a community again.

We didn’t become our first draft of our adult selves in isolation and we will not be able to edit those selves alone either. To re-become is not something we can do hermetically, and we’ll be lucky to know what it’s like to be in a place where we see and we are seen. This will be the hardest part of our 20s, I think: to learn a new way to be part of something again. Luckily, we’ve got a pretty good model to emulate.

Amelia Nierenberg is a senior in Timothy Dwight College. This is her last staff column for the News. Contact her at amelia.nierenberg@yale.edu .