When the Connecticut Juvenile Training School was constructed, proponents said it would be a modern, state-of-the-art facility for juvenile delinquents. Instead, it left behind a legacy of abuse and neglect, landed former Gov. John Rowland in prison and, now, has finally been consigned to oblivion.

Gov. Dannel Malloy announced the closure of the facility, located in Middletown, on April 12, when the last juvenile inmate left the facility. Constructed under the Rowland administration in 2001 after complaints about the conditions of the state’s juvenile facilities, the school nevertheless came to personify poor planning, cost overruns, excessive use of force and a failure to provide teenage inmates with effective rehabilitative treatments. As a result of the closing, juvenile offenders in need of detention will be housed in smaller facilities around the state.

“The Connecticut Juvenile Training School was an ill-advised and costly relic of the Rowland era. It placed young boys in a prison-like facility, making rehabilitation, healing and growth more challenging,” Malloy said in an April 12 statement. “The fact remains that this isn’t a celebratory moment, but a time to reflect on the past mistakes made when it comes to juvenile justice, and an opportunity to create a system that better serves our young people and society as a whole.”

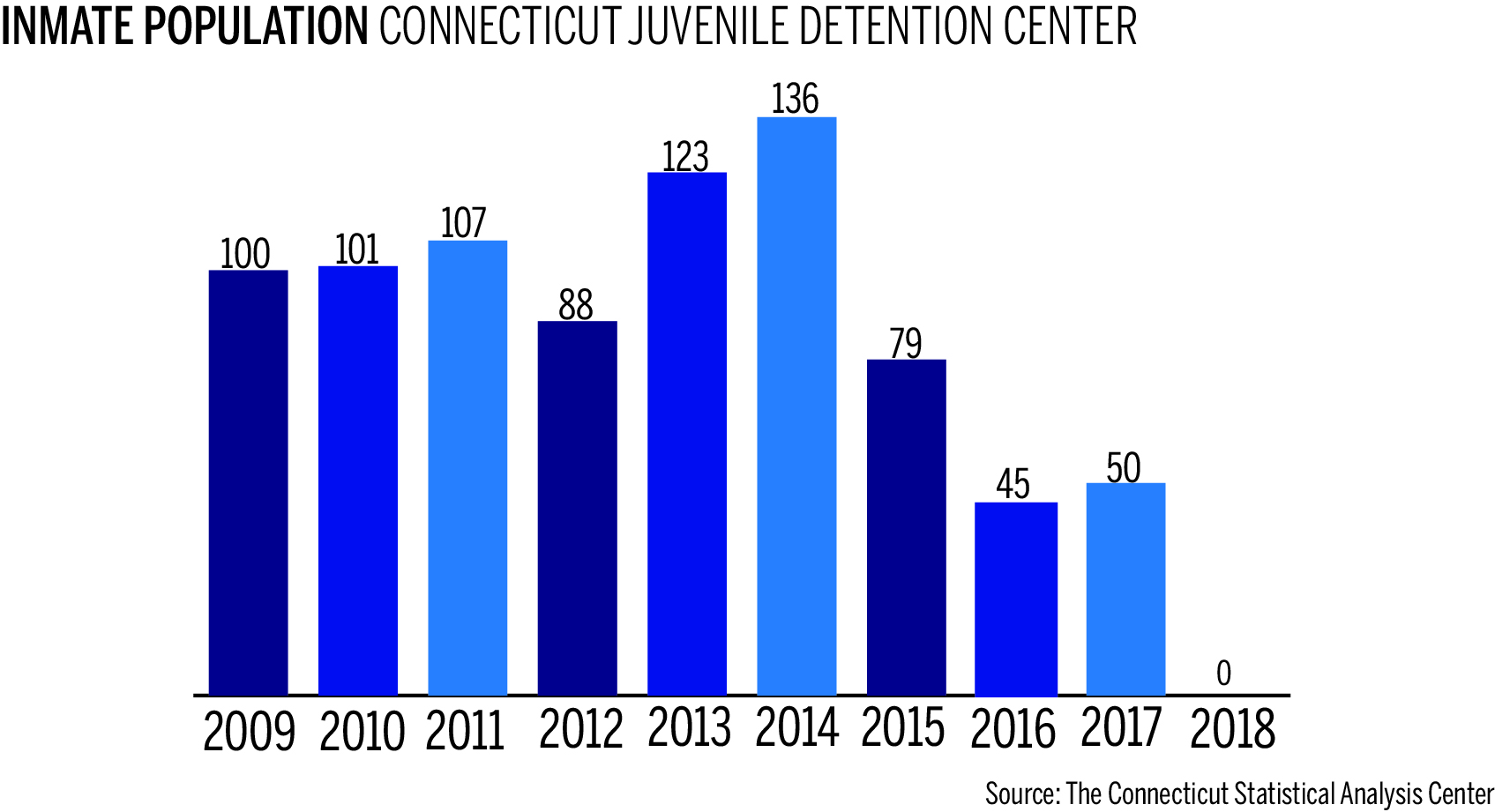

Malloy also attributed the closure to the facility’s dwindling occupancy rate; fewer than 50 inmates over the last two years have occupied the facility, which is designed to accommodate more than 200 juveniles. A rapid decline in crime and juvenile arrest rates, along with state criminal justice reforms, has rendered the facility obsolete, Malloy said, though the juvenile center’s population spiked twice, in 2010 and 2012, when inmates of 16 and 17 years old transferred into the facility. Before that, it housed only those under the age of 16.

Joette Katz, commissioner of the state Department of Childrens and Families, which oversaw the facility, echoed the governor’s assessment, noting that there has been a tectonic shift in the state’s approach to juvenile justice policy in the years since the construction of the Connecticut Juvenile Training School. According to Katz, research has shown that the brains of many adolescents and young adults have yet to fully develop, and community-based treatment programs have proven far more effective than simply locking them up in a confined setting. While the state has around 10,000 juveniles who need some form of intervention, only 30 to 40 of them are deemed to require detention at any given point, Katz said.

“It was really a facility that was designed for a different day and a different purpose,” she added.

According to Mike Lawlor, the state’s under secretary for Criminal Justice Policy and Planning, the detention center was initially modeled on a facility in Ohio, which closed in 2009. While the Connecticut Juvenile Training School was under consideration, questions were raised about the facility’s structure and its construction cost — $57 million in total — and some legislators floated the idea of smaller, separate facilities. But Rowland was insistent on building the large complex, Lawlor said. In 2004, Rowland was convicted of taking bribes in exchange for pushing through the construction project, among other charges.

Lawlor said that the large structure of the training school encouraged a “gang mentality” among teenage inmates. He added that it was designed more to “warehouse” young people than to help them, as the facility was not equipped with many amenities and services that were conducive to rehabilitation efforts. Roughly 95 of the more than 200 cells did not meet the federal standards for window requirement, and were barred from housing juvenile inmates, incurring unnecessary costs for the state, Lawlor said.

“The window is a slit in the wall about three inches wide,” Lawlor said. “There is virtually no natural light, and it’s very difficult for kids to get through the day.”

In 2005, former Gov. Jodi Rell visited the facility and promised to shut it down after giving a harsh assessment of the “prison-like atmosphere.” Rell did not follow through on the promise.

During Malloy’s tenure, the Department of Children and Families has also been criticized by legislators for failing to establish accountability and address abuse in the facility. In 2015, the state Office of Child Advocate released a series of surveillance videos showing the overuse of restraints and seclusion by staff members. Due to alleged mismanagement at the facility, the legislature voted last year to strip the Department of Children and Families of its oversight authority over the center, turning it over to the courts.

State Rep. Joseph Serra, D-Middletown, said that this decision reflected a long-running frustration with the way the department handled the detention center, prompting legislators to transfer management to a branch where they had more confidence. He emphasized that the responsibilities for constructing and overseeing smaller detention facilities now fall on the judicial branch, and the treatment of inmates will continue to be a key concern for the legislature.

“It’s really not an easy situation to handle these young people, so we’ll have to let it play out,” Serra said. “But we will be observing what is going on there.”

Katz declined to comment on the legislative decision.

The Connecticut Juvenile Justice Alliance and the Connecticut Voices for Children both praised the closure. Lauren Ruth, the advocacy director for the Connecticut Voices for Children, said that research has shown that rehabilitation efforts are more likely to succeed when finished closer to juveniles’ homes than in a large correctional facility. Still, she cautioned that the state may be inclined to excessively cut back on funding for juvenile justice under fiscal pressure. According to Ruth, the $17 million presently allocated to the judicial branch may not be enough to adequately fund rehabilitation efforts.

“The legislative, in a time of austerity, is really struggling to figure out what they need to prioritize at this time and provide the adequate fund.” she said.

Connecticut’s prison population reached its peak in 2008 and has been falling since then.

Malcolm Tang | jiawei.tang@yale.edu