Wikimedia Commons

Three months after President Donald Trump signed into law a tax on large university endowment investments, Yale — one of about 30 schools subject to the 1.4 percent tax — is continuing to lobby against the new policy.

According to Associate Vice President for Federal and State Relations Richard Jacob, before the passage of the new tax, Yale and peer institutions proposed a compromise that would provide a tax credit for money the universities spend on financial aid that enables students to attend tuition-free. The credit would be capped so that the institutions would still pay some tax on the investment income. Such an approach, Jacob said, would reward schools that spend more on financial aid.

However, the proposal failed to make it into the tax bill that passed Congress last December. Jacob said two senators also tried to attach the proposal to the spending bill that Congress enacted last Friday but did not gather enough support to move forward.

“We will continue to look for other opportunities,” Jacob wrote in an email to the News, adding that Yale and other institutions affected by the tax are continuing to speak with individual members of Congress.

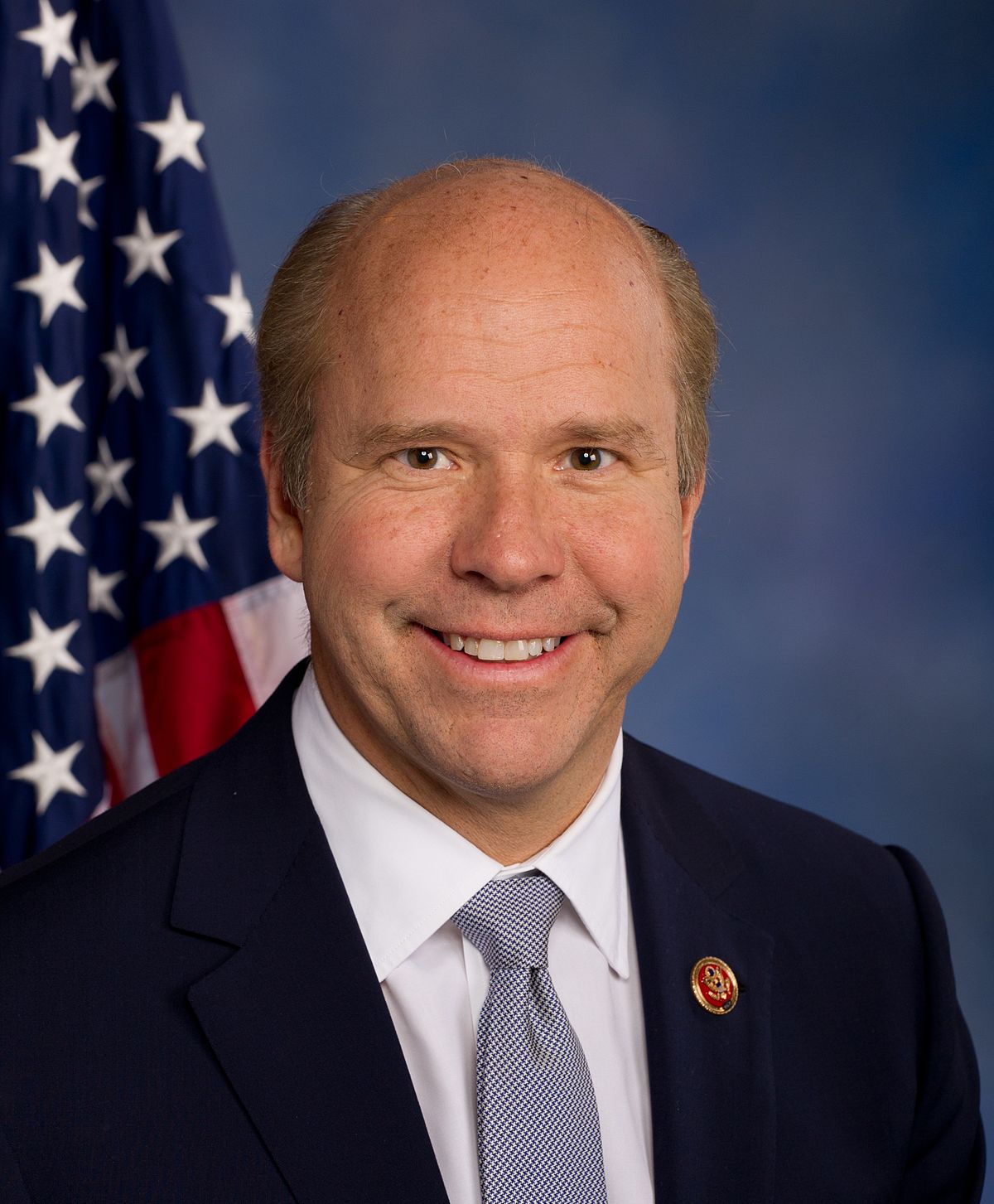

Although opponents of the endowment tax so far have not seen much success, there is hope in the House of Representatives. Representatives John Delaney, D-Md., who announced he is running for president last December, and Bradley Byrne, R-Ala., co-sponsored a bill earlier this month called “Don’t Tax Higher Education” that would repeal the endowment tax.

In an email to the News, Byrne said that because the bill has bipartisan support, it is more likely it will get a vote. Byrne added that he and Delaney will continue to campaign for the bill over the next few weeks and that they hope the issue is addressed by the end of the year.

“We should be doing everything we can to make college more affordable for Americans, and I do not see how taxing college endowments helps accomplish that goal,” Byrne said. “The endowment money is often used for scholarships and research programs, and it does not make sense for the federal government to get involved. It is the epitome of government overreach.”

Byrne added that although the tax in its current form affects only a small number of universities, it opens the door to more wide-reaching taxation on higher education in the future.

Now that the tax is signed into law, the Treasury Department is mandated to issue specific guidelines on how to implement the tax. Jacob said Yale and its peer institutions are working together to provide “consistent, well-considered” comments to the Treasury Department that will address questions such as what counts as investment income and how it is calculated.

Earlier this month, University President Peter Salovey and 48 other university and college presidents signed an open letter urging Congress to repeal or modify the tax.

“The net investment income tax will impede our efforts to help students, improve education, expand the boundaries of knowledge, advance technological innovation and enhance health and well-being,” the letter stated. “Each year we spend funds from our endowments to support this critical work. Endowments are not kept in reserve to be drawn on only occasionally or on a rainy day.”

D. Bruce Johnstone, former chancellor of the State University of New York, told the News that the endowment is a tricky financial concept that politicians may sometimes fail to grasp. He explained that endowments are often critically important for financial aid, which Johnstone said most politicians would not want to jeopardize.

He added that the tax, if kept in place, will likely have a lasting impact on universities’ fundraising abilities.

“People are going to get very unwilling to donate money if what they think they are donating to is not the university but back to the U.S. government, which is already running enormous and growing deficits,” Johnstone said.

Jingyi Cui | jingyi.cui@yale.edu