Bah! You imbeciles wouldn’t know real film if it smacked you over your flabby noggins. Cinema is about confrontation. It’s about violence, and horror, and being so shocked by something that you vomit all over your plastic thingy of Mike and Ikes. It’s about challenging what it means to be human in the most grotesque, horrifying way possible. Some namby-pamby adaptation of a Jane Austen novel or whatever? That’s not cinema. A four-hour-long art film where a couple of opossums beat the shit out of each other while some lady with a husky voice reads passages from Also Sprach Zarathustra? THAT’S cinema.

Now, as you probably know, 2017 was a fucking awful year for cinema. Most every movie was all “pretty” and “inoffensive” and “consciously trying to avoid aestheticizing violence.” I mean, not even ONE of the so-called Oscar front-runners has so much as a single scene where the ghost of Luis Buñuel listens to the shrieks of a woman in childbirth on an old phonograph while he eats a live snake!

But today, I’m coming to you with good news. You see, there was one film that had the audacity to deeply disturb its viewers, to horrify them with scenes so depraved as to render speech, much less judgment, utterly impossible. That’s right — I’m talking about the best movie of 2017, Tony Leondis’ crowning achievement of surreal horror: The Emoji Movie.

Right out of the gate, The Emoji Movie is daring its audience to hold back their screams of agony. We’re introduced to our hero, Gene, as he guides us through a tour of the nightmarish realm of the damned where he resides. The inhabitants of the city are grotesque beyond compare: there is a rabbit with legs sprouting from its neck, a woman whose mouth is twice as large as her torso, and an enormous sentient hand with an ever-shrieking mouth at its center. Here, we are introduced to the film’s central conceit: these abominations spend their lives catering to the idiotic whims of a petulant god who could destroy them all in the blink of an eye, and yet this god does not even know that these creatures exist. They are as mayflies on a summer day to him, incomprehensible and transient. Werner Herzog or Lars von Trier could not have created such a horrid ontology, yet Leondis does it without so much as a second thought.

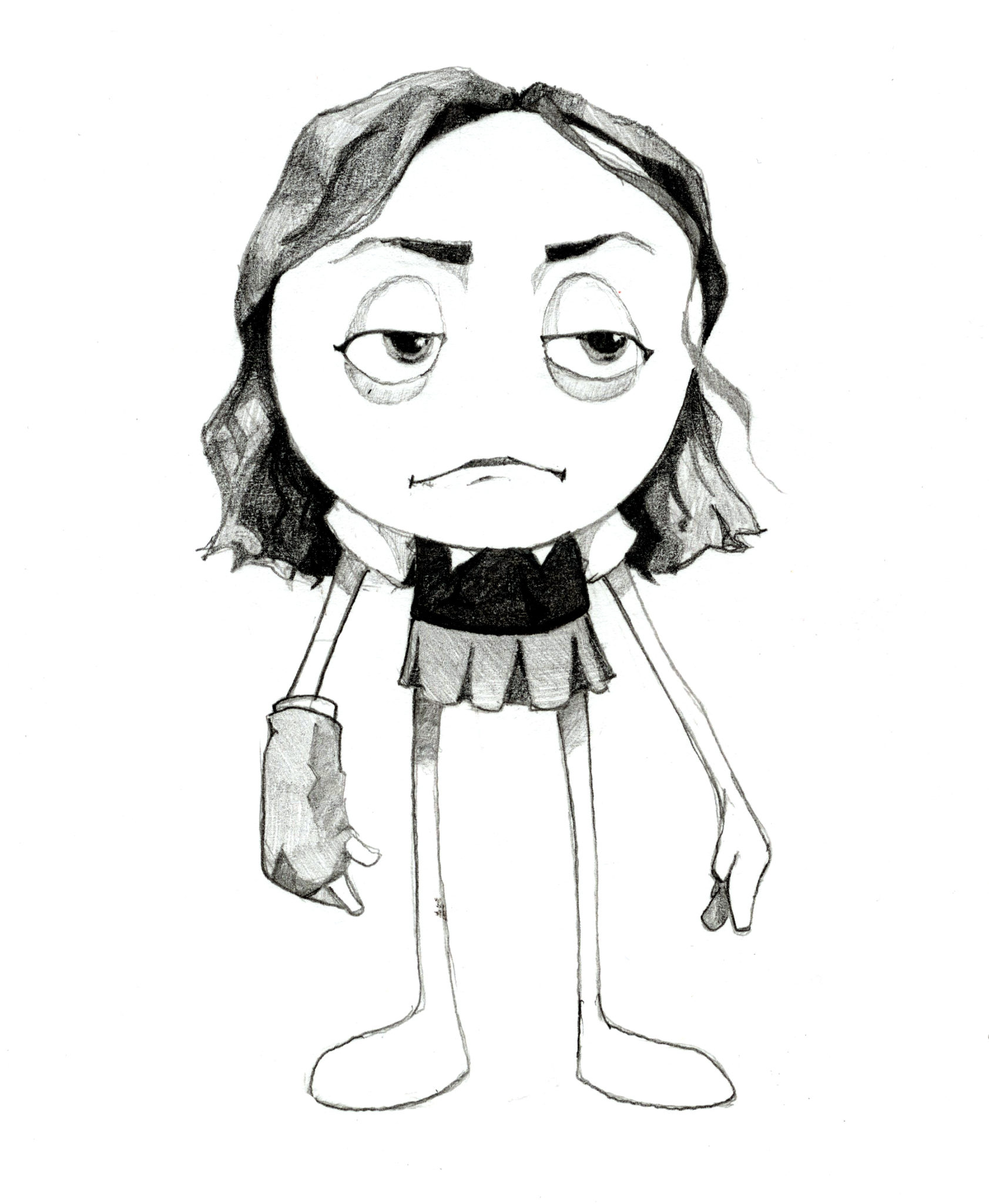

Gene soon realizes he has been gifted with a strange talent, an ability to flow between the categories that his society takes for granted. Of course, he is ostracized by his fellow monstrosities for this; more importantly, the cruel god sees his violation of the hierarchy and decides, not knowing the import of his actions, to destroy the universe entire. Gene, like the Biblical Lot, must leave his Sodom behind; taking with him the disgusting hand-person and a very oddly proportioned lesbian, he embarks on a journey of disenchantment and abject despair. What follows is a nightmarish carnival of body horror to make Cronenberg himself weep. Gene inflates and explodes, splatting his friends with his viscera; the hand eats, vomits out its sustenance, and joyously eats the vomit; in a touch worthy of Julia Ducournau, the hand at one point takes Gene into his mouth and viciously masticates him. Leondis exacerbates the audience’s deep discomfort both with his framing (certain shots recall Mario Bava’s Kill Baby Kill and Yorgos Lanthimos’ Dogtooth) and with his musical choices (sweet, dopey music plays over scenes of stilted dialogue and moral perversion).

Inevitably, the tides of fate bring Gene back to his city, where echoes of The Exterminating Angel have set in: Searching for order in a society facing certain doom, the elders of the town have set up a public execution. Gene attempts to calm the people down, but the mob turns on itself of its own volition, its leaders crushed to death beneath their own colossi. But the end of the universe is at hand. The darkness closes in, and in his confusion and angst, Gene once more sends a signal to the dark god — precisely the same signal he sent before. And the god sees it, and in his capriciousness and ignorance chooses thus to save a universe he still has no idea he controls. In the end, Leondis suggests, the joy that these depraved freaks feel is the joy of serving a god that cares not one iota whether they live or die. Conformity is their only salvation in their benighted universe.

It is that audacity — that sickness, that nihilistic darkness, that refusal to convey any sort of moral — that sets The Emoji Movie apart from any other releases this year. Consistent characters, beautiful settings, and delightful dialogue: these, perhaps, are enough for a passable work of short fiction. But it takes audacity and a sick, sick mind to make a film as disturbing as The Emoji Movie, and I have no hesitation in saying that Leondis has made the film of the year.

Micah Osler | micah.osler@yale.edu