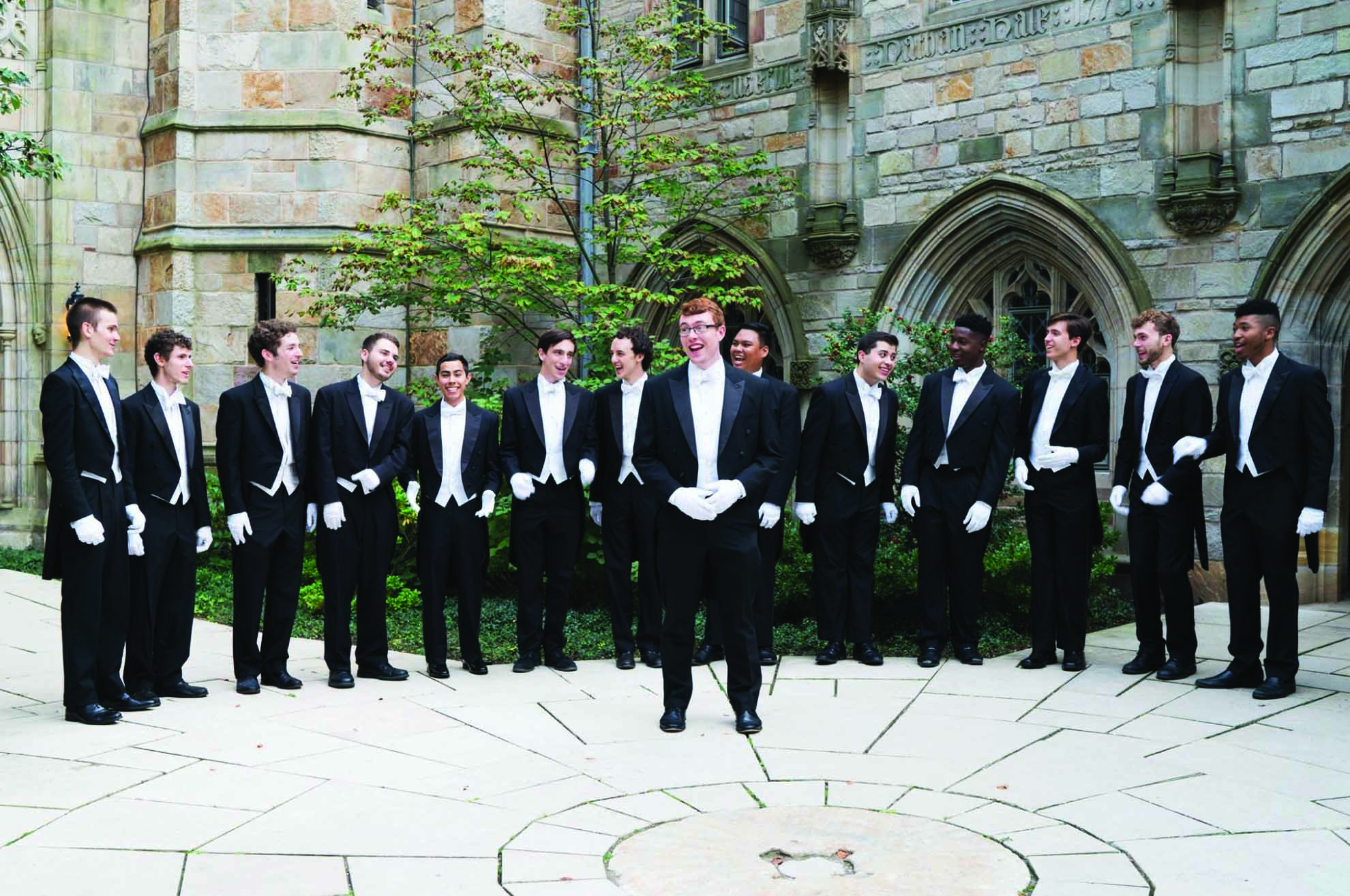

Whiffenpoofs

When nine Yale students came together to form the Whiffenpoofs in 1909, the composition of the group reflected that of the broader Yale community — all-male and predominantly white. Last week, by admitting its first-ever woman, Sofía Campoamor ’19, to the Whiff class of 2019, the group made a historic stride toward inclusivity.

But the newest tap class also breaks with tradition in another significant way: For the first time in recent history, the majority of its new singers — at least eight out of 14 — are members of minority groups. One member of the Whiffs declined to comment on his racial or ethnic identity.

Whiff music director Kenyon Duncan ’19 declined to comment on the new singers’ racial or ethnic identities but stressed that the new tap class is diverse in its musical and artistic talents.

David Martinez ’13, webmaster for the Whiffenpoof alumni website, said that, between 2008 and 2014, he does not think the Whiff classes, each of which consists of 14 singers, had more than four or five members who identified as people of color. And Emil Beckford ’19, a member of this year’s Whiffenpoof tap class who came to Yale in 2015, told the News that, during his time at the University, the Whiffenpoof classes have on average had four or five people of color and one black singer.

Beckford, who is black, said that having two black men in the outgoing Whiff class encouraged him to try out because “there are more people like [him] in this space.” With an incoming class that includes seven to nine black, Asian or Latino members, future prospective members from various backgrounds are more likely to have somebody with whom they can identify, Beckford said.

“It’s really important that people of color are represented in the Whiffs if Yale is championing itself as a super diverse space,” he said. “The group has typically said, in my opinion, that Yale is a place where predominantly white men, often men of privilege, go to school. But if Yale says that that isn’t what it is anymore, then the group should reflect that [Yale] is a place full of people of all races and all genders who come from varying socioeconomic backgrounds.”

According to David Code ’86, the first Whiffenpoof to vote in favor of admitting women in 1986, there was a time when the group did not admit Jewish or black people. Each time a new minority member was admitted, he added, Whiff alumni would protest, saying that “the group was being ruined.”

The all-female senior a cappella group Whim ’n Rhythm has also seen increased participation by people of color in recent years. The singing group has five people of color in its outgoing, 14-member class of 2018 and four in the newest tap class, according to former Editor-in-Chief of the Yale Daily News Magazine and Whim business director Gabriella Borter ’18. The group announced its all-female class of 2019 last week, following its January decision to consider accepting singers of all genders.

For many years, Borter said, there had been very few people of color in Whim. She added that there were only two people of color in the class of 2017.

Borter attributed the increased minority representation in part to the group’s outreach to women from all parts of campus. The all-gender a cappella group Shades of Yale, which celebrates the music of the African diaspora and consists mostly of black singers, has in recent years seen more alumnae joining the Whim, including two in the class of 2018 and three in the class of 2019.

Ashtan Towles ’19, one of the three Shades members admitted to Whim last week, said a current Whim member told her that there were many years when no female singers from Shades auditioned for Whim.

“When I saw Whim tap four black women last year I got excited and saw that Whim could also be a space for me,” Towles said.

The first female Whiff, Campoamor, who is Latina, also emphasized the importance of having a Whiff class that is diverse in terms of ethnicity, gender and socioeconomic status.

In addition to gender, she said, the Whiffs “have a lot to unpack” as an institution in terms of race and gender.

“When we perform for kids and tell them how we get to travel the world by singing, I don’t want anyone to count themselves out of a dream because of an aspect of their identity, because they think they have to look a certain way or be a certain gender,” Campoamor said.

Jingyi Cui | jingyi.cui@yale.edu

Adelaide Feibel | adelaide.feibel@yale.edu