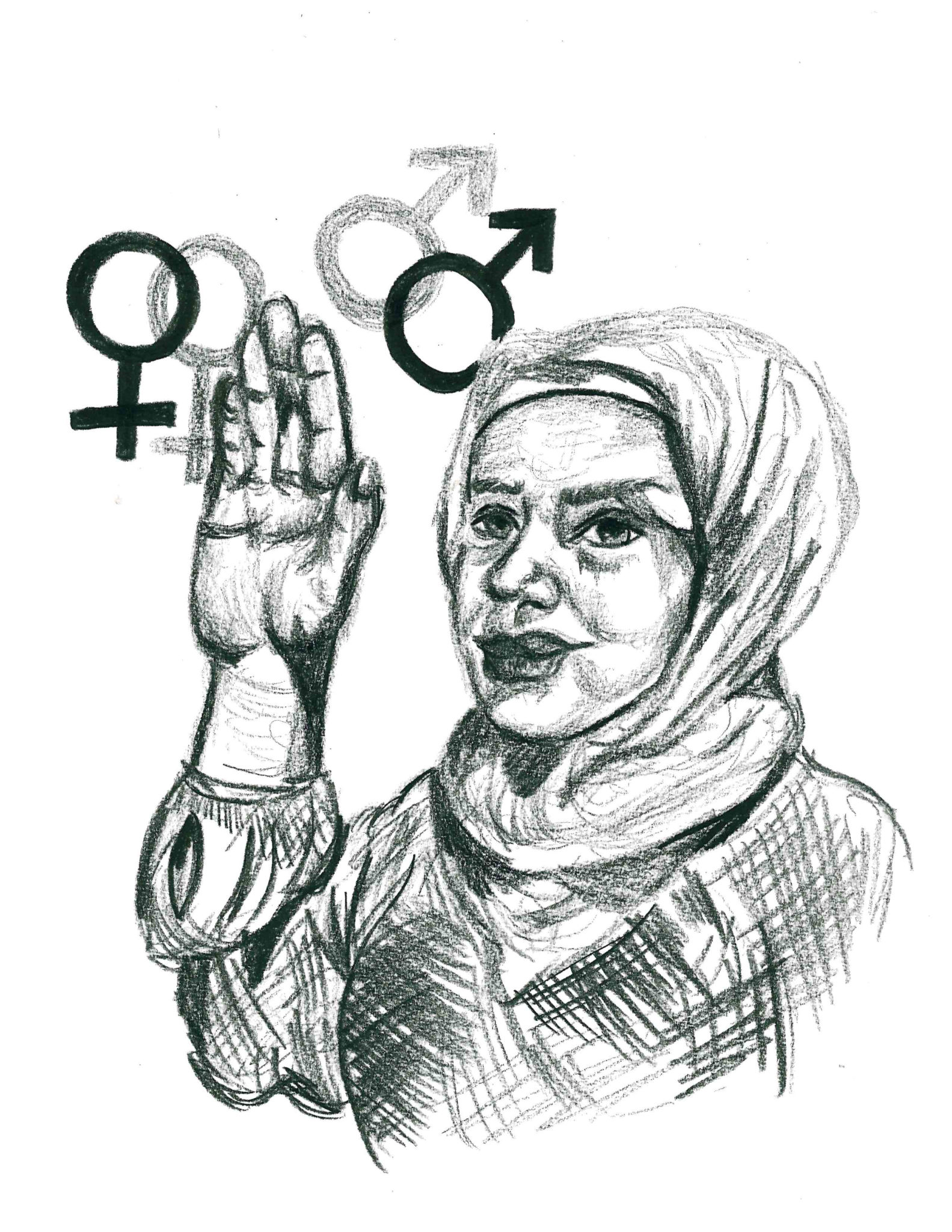

What does it mean to be LGBTQ and a refugee at Yale, in Trump’s America and in the world in 2018?

One year after the issuance of Executive Order 13789, which capped refugee entry into the United States at 50,000 and suspended admittance from seven primarily Muslim countries, over 30 Yale undergraduates, graduate students and faculty members gathered in the living room of the Berkeley Head of College House to discuss not only the ramifications of this administration’s policies, but also dive deep into the lesser-known topic: the perils faced by refugees fleeing due to persecution based on sexual orientation.

The Feb. 3 event featured Subhi Nahas, a Syrian LGBTQ activist and founder of the Spectra Project, a San Francisco-based organization dedicated to providing emergency support, health facilities, education services and protection to LGBTQ minorities in the Middle East and Northern Africa region. Co-sponsored and organized by several campus groups such as the Arab Student Association and the LGBTQ Resource Center, among others, the event attracted attendees from various academic and personal backgrounds.

“Mr. Nahas’ work is of incredible importance but does not receive much media attention,” Malak Nasr, co-president of the ASA, explained when asked about her motivation for bringing Mr. Nahas to campus. “We wanted to raise awareness about these kinds of initiatives that show intersectionality among pertinent issues in the world today.”

Nahas’ talk deftly combined the personal and professional, weaving his own personal story of persecution and eventual resettlement as a LGBTQ refugee from Syria with his advocacy work with Spectra in the years since. He fielded questions from attendees about the organization’s apolitical identity as well as specific policies governing treatment of LGBTQ refugees and individuals in the region. Some attendees of the teas, including members of the Yale Refugee Project groups, brought a wealth of background knowledge of refugee issues to the tea. For others, like Berkeley Head of College Dave Evans, a geology and geophysics professor, the tea highlighted a previously foreign causality between LGBTQ identity and the need to seek political refuge.

“At first, I thought it was more of an intersection between the refugee community and the LGBT community, that a small percentage of refugees were in the LGBT community,” Evans remarked of his preconceptions entering the tea. “What I came to learn later is that in many cases, the sexual orientation is the main reason for persecution. For me, it was an eye-opener, it made complete sense, and so I think it was really important for him to tell that story.”

Graeme Reid, director of the LGBT Center at Human Rights Watch and professor of anthropology and women, gender, and sexuality studies at Yale, explores the impact of sexual orientation on conceptions of human rights from both an academic and activist perspective. Reid’s seminar this semester, “Gender Identity, Sexual Orientation, and Human Rights,” focuses on situating current debates on LGBTQ rights in “historical, cultural, and international context, by looking at the way debates around sexuality and sexual orientation play themselves out in different parts of the world and how this historical background contributes to the discussions and debates that are taking place today.”

At Human Rights Watch, Reid collaborates with the organization’s refugee center to document the abuses LGBTQ refugees often face — psychological tests and invasive and inappropriate questioning intended to “prove” the veracity of claims of persecution based on sexual orientation. Reid stressed the variety of backgrounds of LGBTQ refugees and the impact of internalized regional persecution on individuals’ experiences seeking asylum. As an example, Reid noted the difficulties that many refugee agencies in persuading refugees to state their sexual orientation or gender identity as their reason for claiming refugee status, given their often-traumatic experiences associated with publicly claiming their sexuality in their countries of origin.

In the midst of a series of more large-scale events focused on bringing refugee issues to the forefront, like the Jan. 29 Vigil, Integrated Refugees and Immigrants Services Benefit Concert and the tenth annual IRIS Run for Refugees, the more intimate nature of Nahas tea represents a greater push within Yale Refugee Project to talk deeply about the diversity of experiences among refugees. While the considerable success of one-time events like the IRIS concert and Refugee Run demonstrate an upsurge in student interest in refugee issues over the last year, Yale Refugee Project President Rosa Shapiro-Thompson ’19 noted that the effects of the executive order have prevented Yale Refugee Project from investing time and energy into smaller projects, targeting specific issues faced by refugees in New Haven and abroad.

“Basically, all of our energy was concerned with advocacy after the election and the Muslim ban as the refugee system in the US has been dismantled,” Shapiro-Thompson explained. “This year, we tried to get back on track thinking about what issues we particularly cared about that we feel may be not be talked about enough in the current refugee discourse.”

Trinh Truong, director of advocacy for Yale Refugee Project, also stressed the importance of translating the reactionary activist momentum into long-term change and a renewed sense of commitment to on-campus advocacy.

“The immediate response to the refugee and Muslim ban last year was incredible … Yet, the Yale attention span is short, and now that immigration isn’t front page news, people are forgetting that a version of the Muslim ban is still in place, Nelson Pinos is seeking sanctuary literally across the street, and other New Haven residents are getting deported from the courthouse down the street,” Truong remarked.

To achieve this goal of refocusing campus activism toward sustainable, long-term goals, Yale Refugee Project launched a new advocacy and awareness branch just last year in addition to the organization’s existing direct assistance program that works with refugees in the Elm City. The advocacy branch, among many other things, encourages Yale Refugee Project members to connect their own personal and academic interests with relevant Yale Refugee Project programming and events. Since the branch’s inception, Yale Refugee Project members have established coalitions related to refugee employment, Central American immigration policies and temporary protected status in the United States.

Beyond creating new coalitions, Shapiro-Thompson encouraged board members to connect their own diverse backgrounds and experiences with the diversity of issues faced by specific refugee communities around the world. For Ryan Gittler, advocacy coordinator for the Yale Refugee Project and member of the LGBTQ community at Yale, this meant exploring the intersection of LGBTQ issues and refugee policies both in the United States and abroad. Inspired by Yale Refugee Project discussions about the systematic violence against LGBTQ individuals in Chechnya, Gittler began to consider not only the role of sexual orientation as a motivating factor for fleeing a country of origin, but also the ways he could specifically engage members of Yale community to bring this intersectionality to light.

To develop this initiative, Gittler sought the support from not only the Yale Refugee Project board, but also nonrefugee organizations like the LGBTQ Co-Op and the LGBTQ Resource Center, emboldened by the prospect of uniting the seemingly disparate groups over a shared advocacy goal. Gittler seeked a partnership between the two groups due to the Co-Op’s radical advocacy roots, which date back to the 1980s.

“There’s a very vibrant queer community at Yale which is amazing but that vibrancy, the community does not necessarily lend itself to advocacy for queer people internationally,” Gittler noted. “[Recently], the queer community here [has been] a lot more about making queer spaces on campus which is obviously really important, but I, personally, and the refugee project wanted to start conversations about queer advocacy and protecting queer people internationally.”

Availing himself to the autonomy afforded by the Yale Refugee Project leadership in allowing board members to shape the organization’s work on-campus, Gittler and other members met individually with Prisca Dognon and Ellie Shang, co-presidents of the Yale LGBTQ Co-Op, to discuss ideas for events the two groups could organize as a unit to foster conversation about the unique experiences of LGBTQ refugees.

Chief among these ideas for collaboration was a three-part speaker series this spring, hi–ghlighting the LGBTQ asylum process through narratives of personal experience and legal and policy advocacy. Accordingly, the LGBTQ Co-Op provided both logistical support and funding for the Subhi Nahas College Tea, raising money at their biannual party last weekend. The Yale Refugee Project also hosted Lara Finkbeiner, deputy legal director of the International Refugee Assistance Project and a Yale Law School lecturer last Tuesday, for a dinner speaking event in the Hopper Fellows Lounge. Unlike Subhi Nahas’ talk, Finkbeiner’s presentation focused more on the technicalities of the American asylum system and the legal pathways for LGBTQ refugees to receive asylum. For the series’ final event, Yale Refugee Project hopes to invite representatives from Immigration Equality, a United Nations-based nonprofit organization dedicated to providing legal aid and advocacy for LGBTQ and HIV-positive immigrants.

Audience to all these events, Gittler expressed a desire to reach not only those currently involved in refugee response efforts on-campus, but also members of the Yale community who see a point of connection between their own lives and the struggles faced by refugees across the globe. “The hope is that people who come to these talks are firstly focused on queer issues and then might not necessarily be thinking about refugees,” Gittler said. “And when they come to one of these events that overlaps the two, then they realize the issues are more intertwined than they originally thought.”

Although the partnership between Yale Refugee Project and Co-Op remains in its early stages, Gittler hopes to continue to collaborate with other student groups and cultural centers, like the Afro American Cultural Center, La Casa and the Women’s Center. In a greater sense, however, Yale Refugee Project’s goal of collaboration and intersectionality expands beyond held in Yale’s college dining halls.

Shapiro-Thompson and Truong implore students to look beyond the hegemonic view of refugees presented in the fragments of news and frequent New York Times notifications to which we have grown accustomed. Instead, we must engage on a personal level and see refugee populations with the same level of complexity that we see ourselves: diverse individuals, each facing different challenges and reconciling various aspects of their identities in the pursuit of a better life.

Ryan Howzell | ryan.howzell@yale.edu