“You’re witnessing the results of 5,000 years of sexual repression,” Ang Lee, the director of “The Wedding Banquet,” said during the wedding banquet scene in “The Wedding Banquet.”

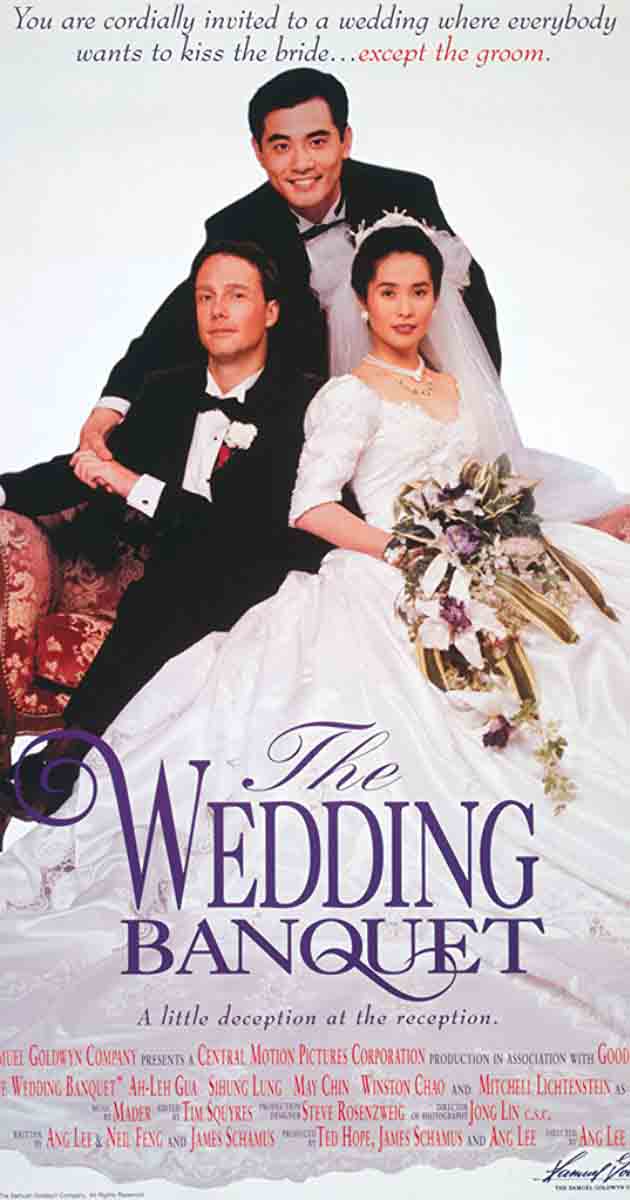

Many of Lee’s films focus on some kind of repression, and Lee’s comment specifies the kind of repression detailed in the aforementioned film — a 1993 motion picture that won the Golden Bear at the 43rd International Berlin Film Festival and was nominated for the Best Foreign Language Film category at both the Golden Globes and the Academy Awards. The film was the most profitable film released in 1993, and was nearly twice as profitable dollar-for-dollar than the year’s runner-up, “Jurassic Park.”

“The Wedding Banquet” follows Wai-Tung and Simon, a gay couple living in Manhattan. The movie opens on clips of Wai-Tung pumping iron at the gym, with Wai-Tung’s mother’s voice message playing over images of Wai-Tung’s sweaty, unamused face. This voice message introduces the film’s conflict from the get-go: Wai-Tung’s parents are traditionalists who are eager for him to marry a woman.

To relieve themselves of this conflict, the couple devises a plan: Wai-Tung will marry Wei-Wei, one of his tenants who is in need of a green card. Wai-Tung’s parents, after being notified of the impending marriage, fly to New York in hopes of taking part in extravagant wedding festivities. They are subsequently disappointed at the sight of a dreary wedding at City Hall, complete with both a sufficiently awkward kiss and equally awkward camera angle. This leads the parents, much to Wai-Tung’s dismay, to host a large banquet commemorating the couples’ pseudo-union. On the night of their wedding, Wei-Wei consummates the relationship, despite Wai-Tung’s aversion, and becomes pregnant.

The film was screened on 35mm at the Whitney Humanities Center, as a feature in the Treasures From the Yale Film Archive Series. The Film Study Center has five Ang Lee films on 35mm, including one of his most widely recognized films, “Brokeback Mountain”(2005). The representative from the Film Study Center provided an anecdote prior to the screening, regarding the first time she saw “The Wedding Banquet” in Tucson, Arizona. “The Wedding Banquet” was not only one of the first movies about a gay couple that had been screened at the theater, but was also one of the first movies with a predominantly Asian-American cast that had been screened at the theater since the 1960s.

Yes, Tucson is in the middle of a desert, so it’s easy to assume that some cultural phenomena just … don’t quite make it all the way over there. But Tucson is a major city, home to the University of Arizona, and currently has roughly 400,000 more people than New Haven. The lack of sufficient representation was, and is, not indicative of a regional problem, but an American film industry problem: the repression Ang Lee comments on in its institutionalized form.

Commentary on repression in the American film industry is a sufficient segue into one particular scene in “The Wedding Banquet” that facilitates discussion. After Wai-Tung and Wei-Wei have their wedding banquet, they are led to a couple’s suite, which is subsequently crashed by intoxicated partygoers. The partygoers play games with the newlyweds, and insist that they will not leave until the newlyweds undress under the covers. After complying to the partygoer’s wishes, Wei-Wei initiates a sexual encounter with Wai-Tung, who is too drunk to physically resist. The last subtitle on the screen before the scene ends is Wai-Tung’s “no.”

This encounter is clearly sexual assault. However, it is difficult to deduce what the producer’s intention for the scene was. Although the image of “no” as the screen goes to black, as well as the exposition of clearly one-sided advances by Wei-Wei throughout the movie — which not only solidify Wei-Wei as an unlikable character, but show her actively ignoring Wai-Tung’s sexuality for her own personal gain — indicate that the producers wanted this encounter to be clearly interpreted as nonconsensual. However, the encounter is never addressed as nonconsensual in retrospect. Wai-Tung’s only comment regarding the encounter follows the lines of “we were drunk, and things went too far” — which is hardly even a partial truth — and Wei-Wei precedes her advance with a comment addressing Wai-Tung’s apparent arousal, as if arousal is a form of consent. (It’s not.)

The scene was over before it began, and no dialogue was opened up between the characters regarding the nonconsensual nature of the encounter. If anything, the moment is quickly bypassed, and the focus of the plot shifts to Wei-Wei’s impending child, and the conflicts that arise between Wai-Tung and Simon. (Spoilers: Wai-Tung and Simon agree to be dual-padres to Wei-Wei’s baby, which makes zero sense to me, because I would not want that woman anywhere near my life.)

If the recent opening of conversation about sexual assault — everywhere, but particularly in Hollywood — has solidified anything, it is that the definition of sexual assault needs to be broadened to protect victims, not perpetrators. “The Wedding Banquet” is a highly progressive film, especially for the standards of a quarter-century ago — it addresses fears of coming out, cultural representation, and sexual repression — but it definitely misses the mark on this issue. The film deserves a watch and plenty of discussion, both about the lingering of past attitudes on social phenomena and how we can upend those attitudes using film and art.

Rianna Turner | rianna.turner@yale.edu