Wikimedia Commons

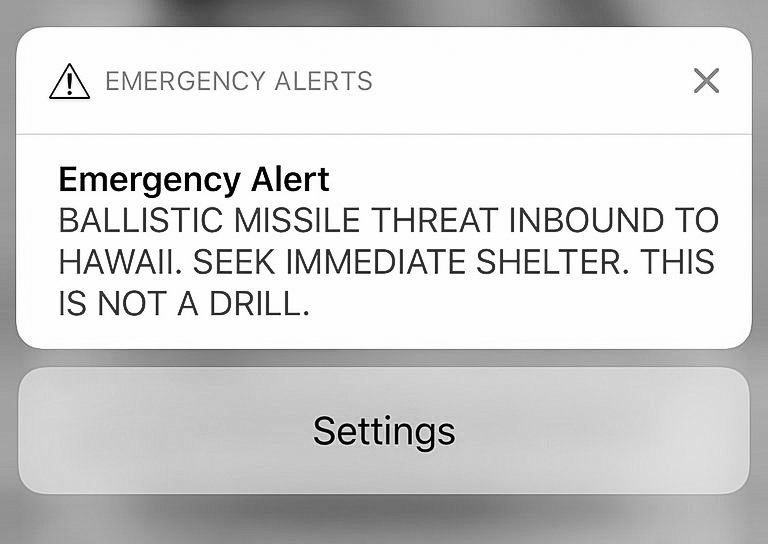

At 8:07 a.m. on Jan. 13, 2018, Lindsey Combs ’19 and Robbie Bickerton ’21 were fast asleep in their homes in Honolulu, Hawaii, when their cellphones blared an alarm. They woke to the news that there was an incoming ballistic missile threat to the island. “This is not a drill,” the emergency alert text message read.

Combs and Bickerton — along with hundreds of others of Hawaiians — received a second text message 38 minutes later informing them that the first message was a false alarm. The governor of Hawaii later clarified that the first text was sent accidentally during a test of the state’s nuclear attack warning system. A HEMA employee had selected the incorrect option from a dropdown menu and triggered an actual alert.

The alert came during a period of rising tensions between the United States and North Korea. Earlier this month, North Korea’s leader, Kim Jong-un, bragged about his country’s nuclear capabilities, claiming that the entirety of the United States is within range of its nuclear missiles. This prompted United States President Donald Trump to tweet that his nuclear button is “much bigger & more powerful” than Kim’s and that it “actually works.”

The state of Hawaii initiated monthly nuclear attack warning siren tests in November 2017, for the first time since the Cold War. Hawaii is the closest U.S. state to North Korea.

The threat of nuclear oblivion may have been false, but the fear felt by Combs and others in Hawaii in the minutes between the two texts was real.

“I didn’t think it was real at first but after a couple of seconds, I realized that I might actually die, so I got up to get my parents,” Combs said. “I was pretty panicked and confused.”

Combs added that she felt helpless since there were no missile shelters in Hawaii that she knew of and because standard advice, such as to stay away from windows, seemed like it would do little to protect her.

After receiving the false alarm text, she wondered whether she would die instantly, whether the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki felt similar to the way they did before they were bombed, whether Native Hawaiian culture would survive if the island were destroyed and how the bomb would look and feel.

Bickerton said that although she was scared when she read the first text message, she and her family did not believe the warning since emergency sirens on the island, recently updated to sound during nuclear threats, did not sound.

“The sirens didn’t go off. It was only the phones, TVs and maybe the radios … so we [thought] maybe it’s a hack or the administration went wrong,” she said.

She added, however, that some other residents took the alert “very seriously,” leading people to drive recklessly, causing injuries.

Combs said she saw several people rush to gather supplies and hide in stairwells and others crying and calling their loved ones.

Makana Williams ’18 was hiking in Hawaii when several people on the trail received the false alarm text message. However, Williams said she did not initially believe the warning was true, partly because only some of the many people on the trail received the notification.

“I felt pretty calm initially but as time went on I started to feel more uneasy, especially because there were military personnel on the mountain and some of them said the notification was true and others said it was false,” she said. “I made it home safely, and shortly after received the official notification that it was a false alarm.”

Although the students interviewed said they were relieved when they learned that Hawaii was not in danger, they also expressed disappointment that a false alarm went out in the first place.

Bickerton said the event revealed that Hawaii was not prepared for a real threat, and that the state’s emergency systems had not been properly set up.

She was even more alarmed that the state’s government took 38 minutes to send a follow-up text even though it “knew right away” that there was no threat, adding that this caused undue panic for Hawaiian residents.

Teava Torres de Sa ’21, a Hawaiian resident who was traveling back to Yale when the alert was sent and only realized what had happened after his flight landed, said his parents and friends told him the alert was received with “a shocking amount of levity.”

“Whether or not this speaks to a public perception of the government as being too incompetent for the threat to have been real or an inability to accept that something so severe and violent could actually happen to our home of Hawaii in the modern day, I’m not quite sure,” he said. “Unfortunately, in either case, I feel the false message lowered guards at a time when we should be most vigilant.”

Combs said that in the aftermath of the event, she had many questions about preventing the proliferation of nuclear weapons, Hawaii’s defenses against a nuclear attack and the likelihood of an actual bombing.

Nine countries, including North Korea and the U.S., possess nuclear weapons.

Saumya Malhotra | saumya.malhotra@yale.edu