Under the Wing

On the evening of Oct. 18, 2017, University President Peter Salovey rose to address a gathering of Yale alumni at an event in Seattle. About a hundred people were settled into the small auditorium’s staggered seating. Behind the stage, the city skyline — with its famed Space Needle — filled the projector screen. Just as Salovey began his speech, a woman leapt onto the stage and faced the audience at large: “Excuse me everyone, can I have your attention please?”

A prominent public figure, an interjecting protester, an imposing security guard hovering in the wings — perhaps more important than the actors on the stage was the protester’s accomplice in the audience, who was recording a video destined for YouTube.

In the video, activist Marlene Blanco brandishes a sign that droops and folds as she paces the stage. “President Salovey: Stop cruel sparrow experiments,” it reads. Below the message, the name of the group that had dispatched her to Seattle is written in cursive: People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals.

Since last May, the Norfolk-based nonprofit has mounted a sustained campaign online and in person against a Yale postdoctoral researcher named Christine Lattin. In her work, Lattin examines how wild house sparrows respond to stress. She induces this stress by placing birds in cloth bags, rattling their cages and adding small amounts of crude oil to their millet.

PETA considers the research torture and the researcher, who has euthanized 250 birds since 2008, a killer. While PETA’s campaign targets her methods not Lattin herself, the group’s tactics have a very personal edge. PETA’s online posts identify her by name, which has enabled internet users to flood Lattin’s email, Facebook and Twitter inboxes with hate mail. PETA has also revealed her home address: of their six protests, one was staged outside her New Haven condo, where she lives with her husband and 20-month-old son.

Meanwhile, the University has defended Lattin. Her methods meet all the guidelines on bird research set by Yale’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and by the Ornithological Council.

Back on stage, Salovey spoke dryly into the microphone, asking Blanco to leave. But she persisted, yelling, “Shame on Yale! Stop killing birds! Shame on Yale!”

The crowd, at first quiet, grew agitated. “Begone!” one alumnus shouted, with a touch of melodrama fitting for the occasion.

“You’re going to have to carry me out!” Blanco yelled back.

A few minutes of pacing later, Blanco left of her own accord; security had called the police, and Blanco decided not to risk arrest. It was clear as she exited the stage that her act was over.

Lattin watches for birds in East Rock Park on Saturday, Nov. 20. (Robbie Short)

***

On a crisp day in November, Lattin, dressed in jeans and a dark cardigan, stepped off a shuttle onto the curb outside the Yale School of Medicine. As we walked toward her lab along the sun-dappled sidewalk, her demeanor scarcely showed the six months of harassment she had endured.

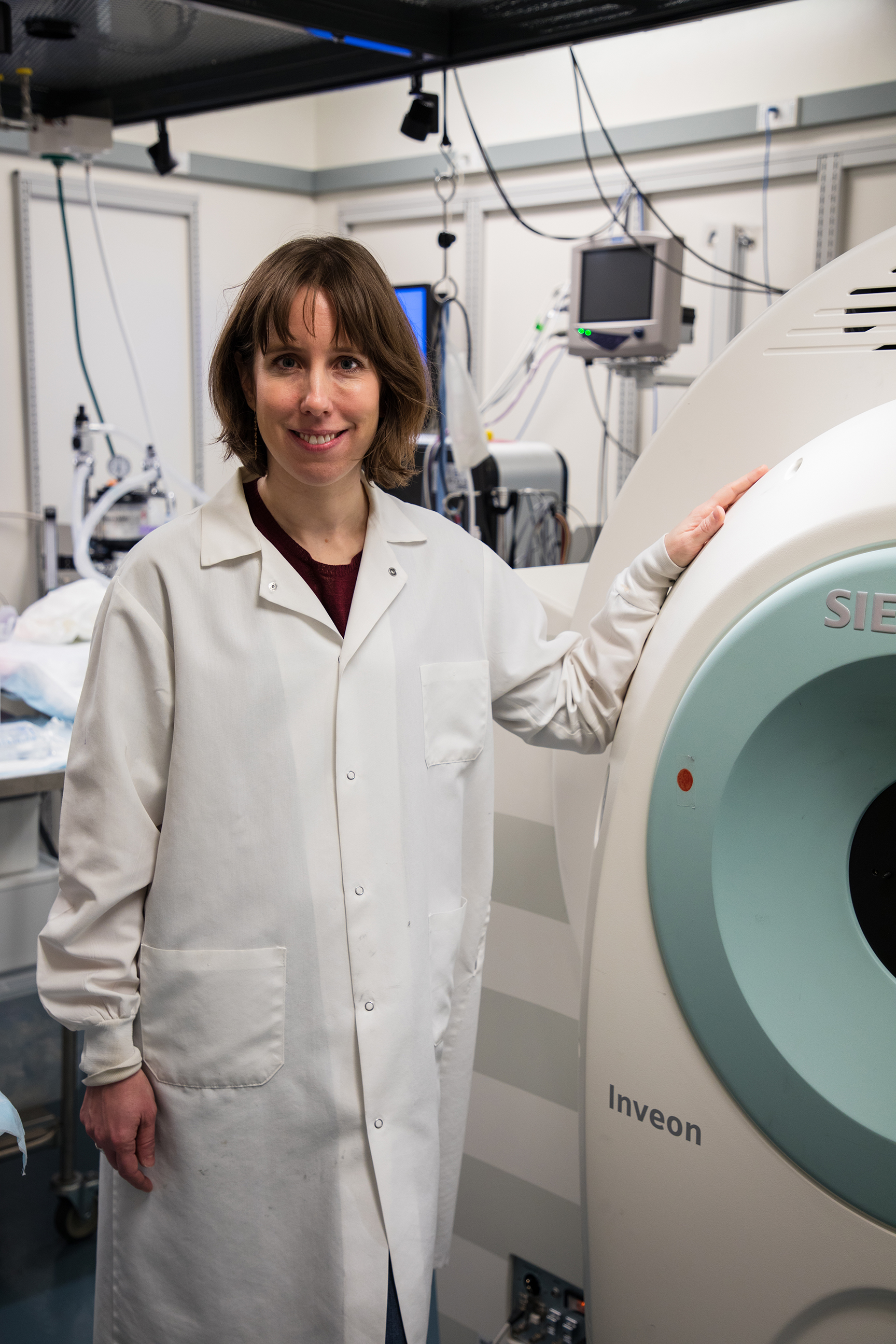

Lattin came to Yale in 2014 after receiving her doctorate from Tufts University. She came to Yale for access to world-class equipment: PET scanners, doughnut-shaped instruments that use particles of antimatter to peer inside the organs of a still-living body. Yale has one of the best PET labs in the world, according to Richard Carson, director of the University’s PET Center and Lattin’s boss. The scanners enable researchers to quantify everything from organ function to brain density by examining how organic molecules, such as sugars or hormones, are concentrated in the various parts of the body. The scanning process is complex and expensive, not least because it requires researchers to have a stock of radioactive molecules on hand to inject into their subjects.

The School of Medicine is a fitting home for such a complex operation. Clinicians use PET scanners to find cancerous tumors; medical researchers use them to make sure new drugs hit their target. Lattin wanted to use them to study how different hormone levels in the brain influence bird behavior.

“It’s kind of amazing to me that they let me put feral sparrows in their million-dollar scanner,” she said. “Not everyone would be as open to doing this work.”

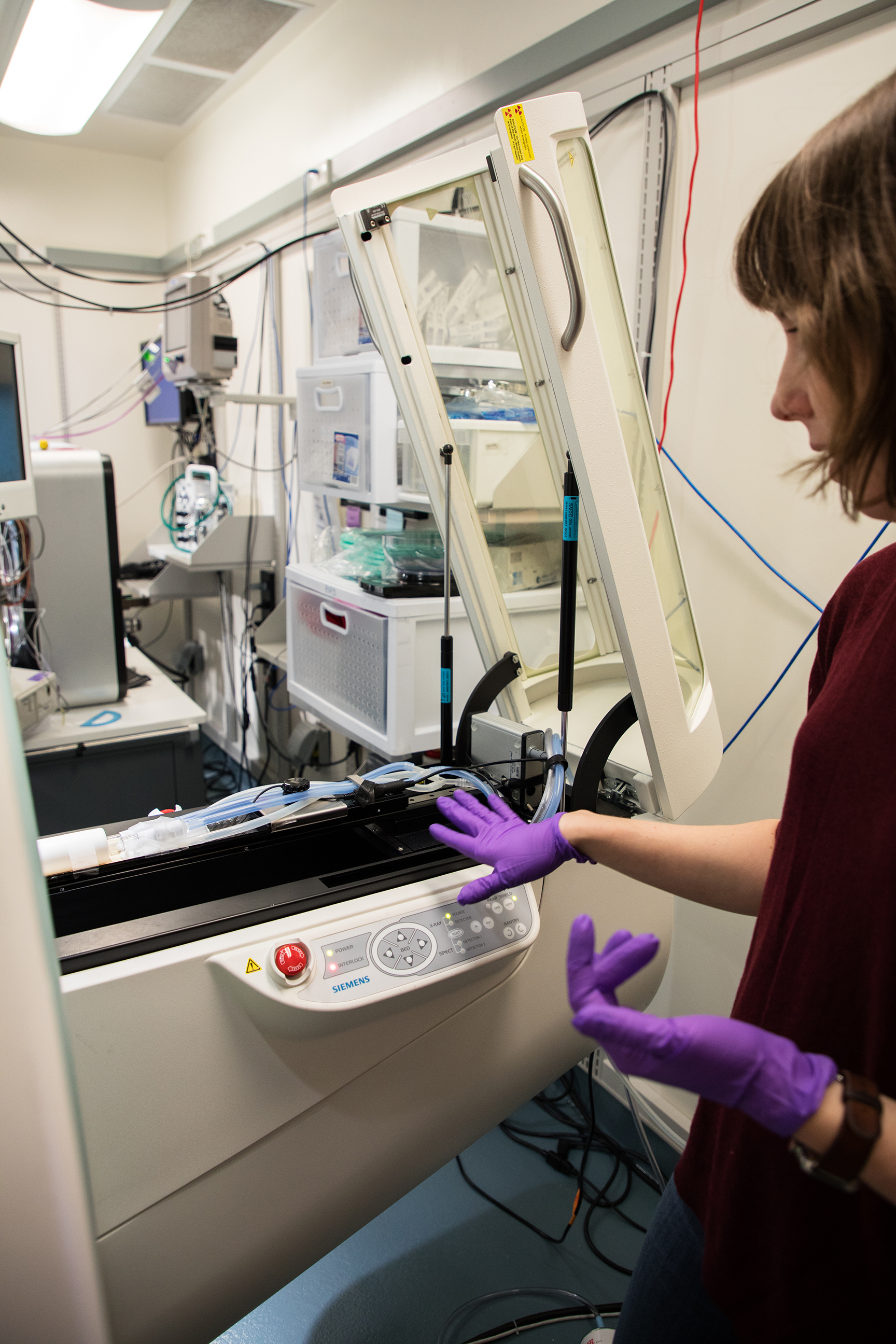

Carson said they had never scanned a bird before. About 25 percent of PET Center scans involve animals, but most of these examine more typical research subjects, such as mice or chimpanzees. Lattin had to develop new techniques to use the scanners on sparrows. She worked with engineers at Yale’s Center for Engineering, Innovation and Design to build a specialized plastic gurney for the birds that holds their bodies steady while they lay anesthetized in the scanner. And she’s had to develop a new method for injecting the radioactive tracer into the sparrows’ tiny bodies.

“Now the birds are being scanned the same way people are being scanned,” said Carson.

The research harks back to Lattin’s time before academia, when she was on staff at animal shelters and other conservation centers. Her work has already contributed to scientific discourse, racking up a total 384 citations, according to Google Scholar. Her crude oil study has been cited by researchers working with dolphins, sea turtles and other species exposed to the 2010 BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico.

Lattin’s study found that even tiny amounts of crude oil induced the birds’ stress response. Even if they appeared normal, the birds’ hormones revealed internal distress. In other words, stress can be hard to detect — in birds being researched or in a researcher herself.

Computer tomography (CT) scans provide a powerful tool, Lattin says, for her research. (Robbie Short)

***

In 1980, PETA began with five members and a philosophy. Since then, its numbers have grown to over 6.5 million — a million and a half more than the National Rifle Association. Inspired by Peter Singer’s manifesto of the modern animal rights movement, its founders sparked a revolution. They believe that the mistreatment of animals is morally equivalent to the mistreatment of any human group. “Animals are not ours to eat, wear, experiment on, use for entertainment or abuse in any other way,” the PETA slogan goes.

Among the general public, PETA is perhaps best known for its provocative advertisements, which advocate for adoption of a vegan lifestyle. Provocative puts it lightly: In a recent Thanksgiving-themed ad, a family happily slices into a roasted human child, dressed like a turkey. But PETA’s efforts at persuasion don’t stop with consumer choice. Among other watchdog agencies, PETA has a department devoted to investigating and lobbying against the use of animals in academic and commercial research.

PETA’s lab investigators first looked into Lattin’s work last year, after an article published in the Yale Engineering magazine detailed her collaboration with the CEID.

A few things stood out immediately, said PETA’s chief of laboratory case management Alka Chandna. Lattin’s abstracts made no mention of the potential human benefit of her research. Chandna and her colleagues doubted that Lattin’s discoveries in wild sparrows could be applied to other bird species — let alone humans.

“Right away, we can say, ‘She’s harming animals and there’s no human benefit,’” Chandna said.

Ingrid Taylor, a veterinarian on staff at PETA, pored over Lattin’s articles, searching for evidence of cruelty in the experiments she conducted at Yale and Tufts. For Taylor, the worst part was that these were not accidents that occurred during the course of research — they were part of the research itself. Lattin’s crimes were premeditated.

In May 2017, PETA, evidence in hand, sprang into action. It filed complaints with the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the district attorney of Middlesex County, Massachusetts, where Tufts is located. (Most states, including Connecticut, exempt research animals from their cruelty laws, but Massachusetts does not.) Then, the campaign for popular opinion began.

“Right from our inception we’ve known that media is critical to our work,” said Chandna. Social media has only made it easier to amplify their message. It’s a change for Chandna, who’s been involved with animal rights work since the 1980s. It used to be that, as an undergraduate, she would spend $15 to order VHS tapes from PETA through the mail. Now, videos surface right in your news feed.

One such video begins with a photo of Lattin holding the blue plastic device that keeps the sparrows in place while they are in the scanner. She’s grinning directly into camera. “This woman is torturing songbirds,” reads the superimposed text. The video has over 2 million views on Facebook and about 9,000 “angry” reactions.

“You better believe that we’re sponsoring advertisements on Facebook,” Chandna said. “You better believe that whenever there’s an opportunity to get this video footage in front of people, we’re doing that.”

PETA has used other channels as well, sending letters to the Yale President’s Office and appealing to alumni for support. A recent alumna, Hanh Nguyen ’17, first heard about Lattin’s research when she started working for PETA the summer after graduation. She wasn’t personally involved with the campaign until October, when she joined a group of demonstrators outside a Yale Corporation meeting at Woodbridge Hall. That month, she sent a letter to alumni organizations, urging them to express their disapproval of the experiments.

Lattin stands next to her PET scanner. (Robbie Short)

After the first online posts against her in May, Lattin’s inbox started filling up with messages from unfamiliar addresses. Some described her research in a way she didn’t recognize. “Unsuspecting birds who have been lured to feeders and trapped or netted are being systematically tormented to induce stress and fear,” read one. Others addressed Lattin directly: “SHAME ON YOU” and “STOP TORTURING BIRDS YOU SICK FUCK!” Notably, a majority of messages criticized the alleged purposelessness of Lattin’s work.

At first, Lattin thought it would blow over. Things weren’t too bad for Lattin — the controversy didn’t even show up on the first page of Google results for her name. Some colleagues advised her to keep her head down. This type of incident hadn’t happened at Yale in about a decade. The last target — Marina Picciotto, a neuroscientist studying addiction — remained at Yale.

A turning point came when PETA protesters demonstrated outside a conference in Long Beach, California, where Lattin was presenting. Lattin described the experience of having protesters shout her name while she spoke to her colleagues as “incredibly traumatic.”

The situation worsened. Lattin could tell by spikes in harassment whenever PETA uploaded a new post. Some of the messages she received were so threatening she shared them with the New Haven Police Department. She also keeps a file on her computer in case something happens to her, so she can have evidence to provide the FBI.

Chandna thinks it’s regrettable that Lattin has felt threatened, but she emphasized how PETA’s communications have been polite. “Clearly, our intention is never to have people be harassed,” she said. “It is never our intention to stir up the masses.”

As for the protests PETA has organized, Chandna doesn’t see them as harassment. Rather, she sees the tactics against Lattin as similar to those deployed by any other campaign for social justice.

“I don’t even think of home demonstrations as being harassing,” she said. “And I like to remind people that the body count here, the harassment here, has been done by Christine Lattin. There are more than 250 birds that have been captured from birdfeeders.”

Taking a step back, for Chandna, Lattin’s work represents one battle in a larger “war on animals” being waged by researchers across the country — against which PETA’s prepared to fight back.

“If you’re going to take Vienna, take Vienna.’” Chandna said. “That’s PETA’s modus operandus [sic]. We’re in it to win it.”

Lattin looks at her scans from the other side of a glass panel in her lab. (Robbie Short)

***

When Lattin needs more sparrows, she gathers a mix of potter traps and mist nets and goes herself to catch them. The sparrows she finds are an invasive species, introduced to North American cities in the 1850s as a solution for urban pests and a salve for homesick European immigrants. They’ve since spread across the whole continent, which is one reason Lattin felt comfortable using them in research — she knew they weren’t going extinct anytime soon.

Lattin acquired her bird-handling skills as a young science educator at the Glen Helen Raptor Center, near Springfield, Ohio. The center is part nature preserve, part animal shelter for the area’s birds of prey. Primarily, Lattin led grade-school children on hikes and taught them about local bird populations. Toward the end of her time, she became an assistant to the veterinarian on staff. Sometimes, she said, birds would be brought in who could not be saved. While the vet euthanized them with a syringe, Lattin held their bodies still.

“That was really hard for me,” she recalled, taking a long pause. “It was pretty sad. But you know, definitely better than … starving to death is definitely a worse way to go.”

In her current research, Lattin prides herself on her ability to handle birds deftly, injecting them with radiotracer and taking blood samples. By doing things smoothly, she minimizes the stress birds otherwise would have felt from having someone reach into their cage or pull them out of a net.

Enjoying the work at raptor shelter and subsequent nature preserves, Lattin moved to Eastern Kentucky to study birds full time. To obtain her degree, she chose a topic not far from her undergraduate work in linguistics: analyzing the songs of the blue grosbeak, a seedeater common to the southern United States. Male grosbeaks sing to impress potential mates and, like human speech, their songs are made up of a complex line of syllables strung together by the singer. And like some humans, when male grosbeaks get worked up, they blow a gasket, launching into a tirade of syllables several times longer than a typical song.

Lattin wanted to capture these tunes in the wild, so she packed up her recording equipment and drove to where most humans stayed clear — a local chemical weapons depot. The 14,000 acres of uninhabited land had become a haven for wildlife, favored among local hunters, and the perfect spot to record birdsongs on a spring morning. Lattin got out of her car and started unpacking her equipment. Immediately, she noticed something was off. It was April, peak breeding season. The hills should have been alive with the sound of birdsong. Why was it so quiet?

The answer, it turned out, was weather: A harsh late May frost had shocked the local ecosystem, halting flowers at the bud, hardening the ground and scattering the insects. Without grasshoppers to eat or seeds to chew on, there was no sense trying to attract a mate. “Of course, I was like, ‘Oh my god, what am I going to do?’” recalled Lattin. “I’m trying to do this research project on song and the birds aren’t singing. But for them, it made sense.”

The frost was a stressor, a threat in the birds’ environment that influenced their behavior — like a lion on the savannah or the loss of control from captivity. While eventually grosbeaks returned to the area, the spring silence alerted Lattin to stress as a phenomenon worth studying further. And so her research began.

The container in which the birds rest while in the scanner. A bird's head sits in the white cylinder, which delivers anesthesia. (Robbie Short)

***

“It is amazing that they chose Christine,” Carson said. Given that a lot of animal research is done at Yale, Carson and his colleagues struggle to rationalize PETA’s unilateral focus on Lattin. “Whether that’s because they think more people will care about birds than care about mice and rats,” Carson said, “I don’t know.”

Lattin has her own theories, but mostly she feels vilified unfairly. She’d deliberately switched to PET scanning because the procedure was less invasive. In the future, she hopes to be able to release caught sparrows back into the wild with tiny transmitters so as to track and, later, recapture them. Not only would that be better for the birds, it would be better for the research.

It would feel better for Lattin too. She’s never liked killing the birds, but legally, that’s the requirement: her scientific

collector’s permit, issued by the Connecticut Department of Energy & Environmental Protection, doesn’t permit her to release captured birds back into the wild. The department has an interest in reducing sparrow populations. They’re invasive, and they compete for nest space with local species like bluebirds, whose numbers have declined in recent decades. The permit isn’t something Lattin likes to talk about publicly because she fears it will sound like she isn’t taking responsibility for her work.

PETA has repeatedly argued that Lattin should stop using animals altogether and switch to modern methods, like computational modeling. This perspective misapprehends the state of alternate methods, Lattin said. It’s hard for her to think of something more modern than PET scans. And without animal research, she said, “all scientific discovery would come to a screeching halt.”

Where Lattin prepares the birds to be scanned. (Robbie Short)

Throughout the controversy, the Yale STEM community has come to Lattin’s defense. Graduate students in biology and immunology have written op-eds in her defense, and in October, an undergraduate chemistry and molecular, cellular and developmental biology major circulated a letter of support. One hundred and twenty people have signed.

Lattin’s case has garnered attention from outside Yale as well. Science magazine and the New Haven Register both covered the story. Other concerned researchers, like Kevin Folta at the University of Florida, have sought to protect her reputation. Folta, who has faced protests himself for research on genetically modified organisms, wrote a paean to Lattin on his blog and hosted her on his podcast. Folta believes she is being targeted because, as a young female scientist without tenure, she is vulnerable.

But perhaps the most vigorous defender of the research has been Lattin herself. She has replied to PETA’s claims on Twitter, rewritten her personal website to make it more accessible and made an effort to speak to journalists interested in her case. So far, that seems to have helped — after she started to speak out, the harassment declined.

“A few people early on said, ‘Oh well, keep your head down and it’ll blow over,’” Lattin said. “I kind of think those people are wrong. If you don’t speak up for yourself, you don’t make it easy for people to rally around you.”

***

Though many have flocked to Lattin’s defense, PETA remains undeterred. It will continue its campaign; Lattin will continue her research, though her current focus is elsewhere. This semester, she is teaching the undergraduate class “Comparative Physiology” for the Ecology & Evolutionary Biology Department. And she’s searching for a professorship — somewhere she can run her own lab.

Although PETA’s aim has been to stop Lattin’s research, the experience has only hardened her resolve. PETA’s accusations have not undercut her belief that the work she does is important, that the questions she’s asking need answers and that, without plausible alternatives, work that kills sparrows is justified.

PETA emphasizes that Lattin’s research has no direct application; she’s not working on a new drug or developing a new conservation method. Lattin and her supporters argue scientific inquiry doesn’t work that way. Sometimes research directly solves a problem or answers a question, sometimes opening up space for more.

PETA argues the animals aren’t ours, for research or otherwise. Chandna said the group only approves of animal research that meets the same standards as human trials. Latin says she’s as humane as possible.

“I’m good at this work. And I try to do it in a really thoughtful and respectful way, and be ethical in everything that I do,” she said. “Who do I want to do this research? I want it to be people like me.”

For PETA, Lattin’s research on birds is yet another piece of evidence in their larger case against animal research. For Lattin, that research is her life’s work.

There’s one point both sides can agree on: justified ends and justified means.

Lattin peers down the tunnel in her scanner. (Robbie Short)