As part of a new carbon charge initiative implemented at Yale in September, administrators across the University have received monthly reports on how their buildings’ carbon emissions compare with the rest of Yale’s. At the end of the year, each administrative unit — like the Faculty of Arts and Science, Yale Law School or the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library — will be charged based on its performance.

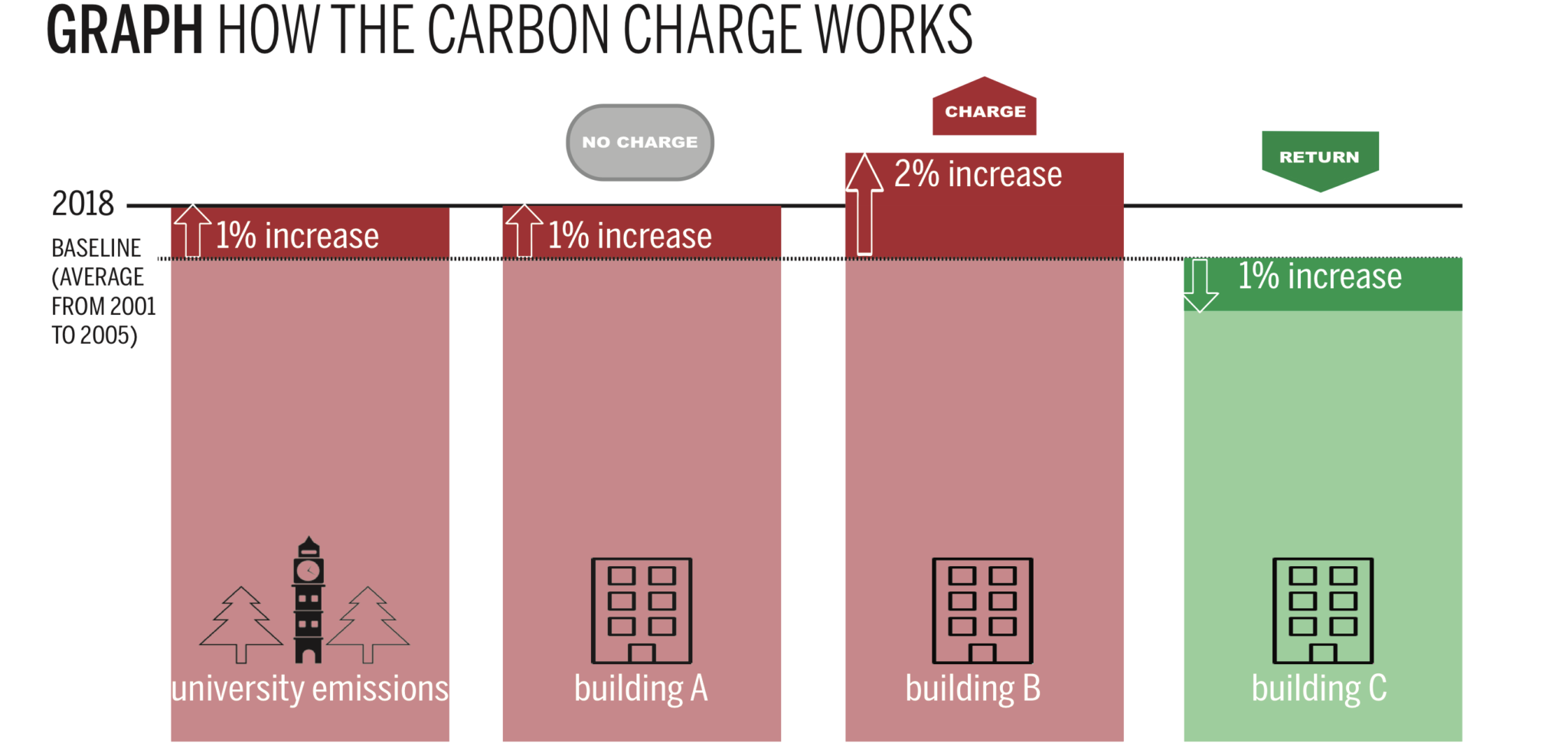

Half a year into its implementation, the Carbon Charge Project at Yale — the first of its kind in the world — has prompted different parts of the University to think creatively about ways to reduce carbon dioxide emissions. Under the current scheme, administrative units responsible for buildings on campus that produce more pollution than the University average are charged $40 per metric ton of carbon dioxide. Units that beat the average receive funding.

“Within the world of carbon pricing, Yale is gaining a reputation, a really good reputation,” said project director Casey Pickett, who was recently invited by Turkey to speak at the United Nations Climate Change Conference. “Word is out that Yale is implementing this first of its kind, internal carbon pricing experiment.”

The idea for the project originated with Yale economics professor William Nordhaus ’63, a leader in the effort to develop a “social cost of carbon,” a monetary equivalent of the damage that carbon causes. Yale chose the current scheme, a revenue-neutral approach that shuffles charges and revenues related to the program among units, following a two-year-long pilot study that tested four different schemes on 20 buildings at Yale. The project now covers more than 250 buildings.

Although the economic punishment or reward for a certain unit is small compared to its annual budget, Pickett said having the carbon charge in place makes carbon a priority for the administrators.

“Sometimes people who are passionate about conservation may feel like the desire on their part may not be respected or may not be the most important thing to bring up in a meeting,” Pickett said. “But when there is an actual charge, then people who care about it anyway might be more empowered to say ‘this matters, this is money.’”

The project, one of six sustainability goals that University President Peter Salovey outlined last year, has touched every corner of the University. The administrators of Kroon Hall, which houses the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, have made the building’s energy data easily accessible on touch screens installed in the first floor. Sterling Memorial Library has completed a lighting retrofit to save energy since the project began, while the Whitney Humanities Center sent out an email reminding its staff and faculty to close up windows, turn off lights and report running faucets.

When he pitched the idea at the quarterly meetings for lead administrators and operations managers last year, Pickett said, he was encouraged by feedback from the staff.

“The vast majority [responded] almost to the word, ‘Okay, I get it. I’m on board … And tell me: how do I reduce my carbon charge?’ which is exactly the answer that we want,” Picketts said. “To answer that question is a difficult one, but it’s the right question to ask.”

Cathy Vellucci, senior director of business operations at the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, said that although it is still too early to tell whether the changes she and her colleagues have implemented will reduce the amount of carbon dioxide the faculty produces, she is hopeful that the administrative attention paid to the project will pay dividends.

“We owe it to future generations to try,” Vellucci said.

Becky Sender, deputy director of finance and administration at the Yale Center of British Art, said the museum has already incorporated the carbon charge into its annual budget planning.

She added that Pickett was good at getting the word out and had been available to discuss the project with her and her associates.

Although the museum’s ability to change its heating operations is limited, because items in its collections must be conserved in specific environments, Sender said the YCBA has set new points for temperature and humidity in response to the project.

“We have always tried to be conscious of our energy usage, but this program helps bring further awareness to a broader range of our staff,” Sender said. “It’s not much trouble, administratively or operationally, and it’s the right thing to do. We want to do our part.”

The Carbon Charge project also presents an opportunity for students to gain hands-on experience within the field of energy conservation. Mike Oristaglio, director of the energy studies undergraduate program, said students in his class helped design a questionnaire sent to around 250 building managers last spring to measure their familiarity with the carbon charge.

The residential colleges will join the carbon charge project in the spring semester, said Tanya Wiedeking, operations manager at Pierson College and liaison for the project in Yale College.

During the pilot study in which Pierson College participated, Wiedeking led a group of students to create a winter break checklist posted to all the doors in the college calling for students to close windows and turn off heaters. Students who returned their completed checklists were entered into a lottery to receive a prize, Wiedeking said.

“It seems to me that this is an area where Yale University is a true leader,” Wiedeking said. “It’s very exciting to be part of this pioneering scheme.”

Jingyi Cui | jingyi.cui@yale.edu