Daniel Greco is the director of undergraduate studies at Yale’s Department of Philosophy. Before moving to New Haven, he studied at Princeton, Cambridge and MIT. He focuses on epistemology, the study of knowledge and rationality. Perhaps it is no surprise, then, that he is an unusually rational consumer and hyperaware of the limits of his own knowledge. We sat down to talk about money for the third interview in this series.

So, how does a philosopher think about money? Deeply: “The limits of our ability to know is one of my main interests. An appreciation of what I’m not able to know is important in financial decisions. That’s why, when it comes to investing, I don’t try and figure out what the most promising investment strategy is on the first-order merits. I just put all my money in low-fee mutual funds. It’s precisely that I know that I’m not in a position to beat the market.”

From the start, it’s clear that Greco is well ahead of most thirty-somethings. Just under half of American families have nothing saved in a retirement account — those who have committed to ongoing, responsible savings plans are even more rare. And as for what he is doing with his money? A low-fee mutual fund is usually an index fund — a basket of hundreds or thousands of individual stocks, which tracks an index like the S&P 500 or a sector of the economy, such as technology. Investing money in an index fund (or several) is the most widely recommended investment strategy for individuals. It allows investors to reap the benefits of investing in thousands of companies across sectors and borders without paying enormous fees or having millions of dollars to spend.

How did Greco end up with this strategy? “With Yale, there’s a retirement plan. We’re with TIAA-CREF, which uses Vanguard funds. My wife read David Swensen’s book, “Unconventional Success,” and we just took from there the suggestion of the mix of assets to shoot for.”

I’ll note here that Vanguard is the world’s largest provider of index funds and at the forefront of the low-cost investment movement. Swensen is the legendary chief investment officer of Yale’s $27 billion endowment and a notable champion of passive, index-fund investment for individuals.

Greco continues, “(My wife) was maxing out her 401(k) contributions. I let Yale nudge me. They’ll automatically put in 5 percent of your salary and match that each year, so I started out putting in the 5 percent. Then the nudge is that every year you work there, they’ll bump up the contribution (not the matching) by another 1 percent.”

It’s becoming clear that Greco prefers to remove his own judgement from the equation, so I ask about his take on the growing number of services that “automate” users’ financial lives. Before answering, he gives me a demonstration of his affinity for automation: “Tile,” a wireless tag on his key ring that he can track with his phone. He says, “I never have to pay bills; I set that up to auto-pay. I’ve never had a late credit card payment. That requires that you give yourself enough margin for error in your checking account, but if you can do that, it’s just so much easier to not have to constantly be remembering.”

It’s strange to me that someone so clearly well-read and intelligent would be interested in letting computer programs make financial decisions for him. But his explanation is perfectly logical. “There’s this research I’m thinking about — willpower is like a muscle. You do build it up over time, but you can also deplete it. You’ve got a finite store of it at any time. Mental energy, right? If you have to be spending a lot of mental energy on stressing out about which bills were due when, that’s going to leave a lot less room for other things you want to be worrying about. You can imagine if you didn’t take advantage of all these automating things, if you could try to make decisions at a much more fine-grain level, maybe you’d be able to make better decisions, but there’s a cost to spending all that time and making all those decisions.”

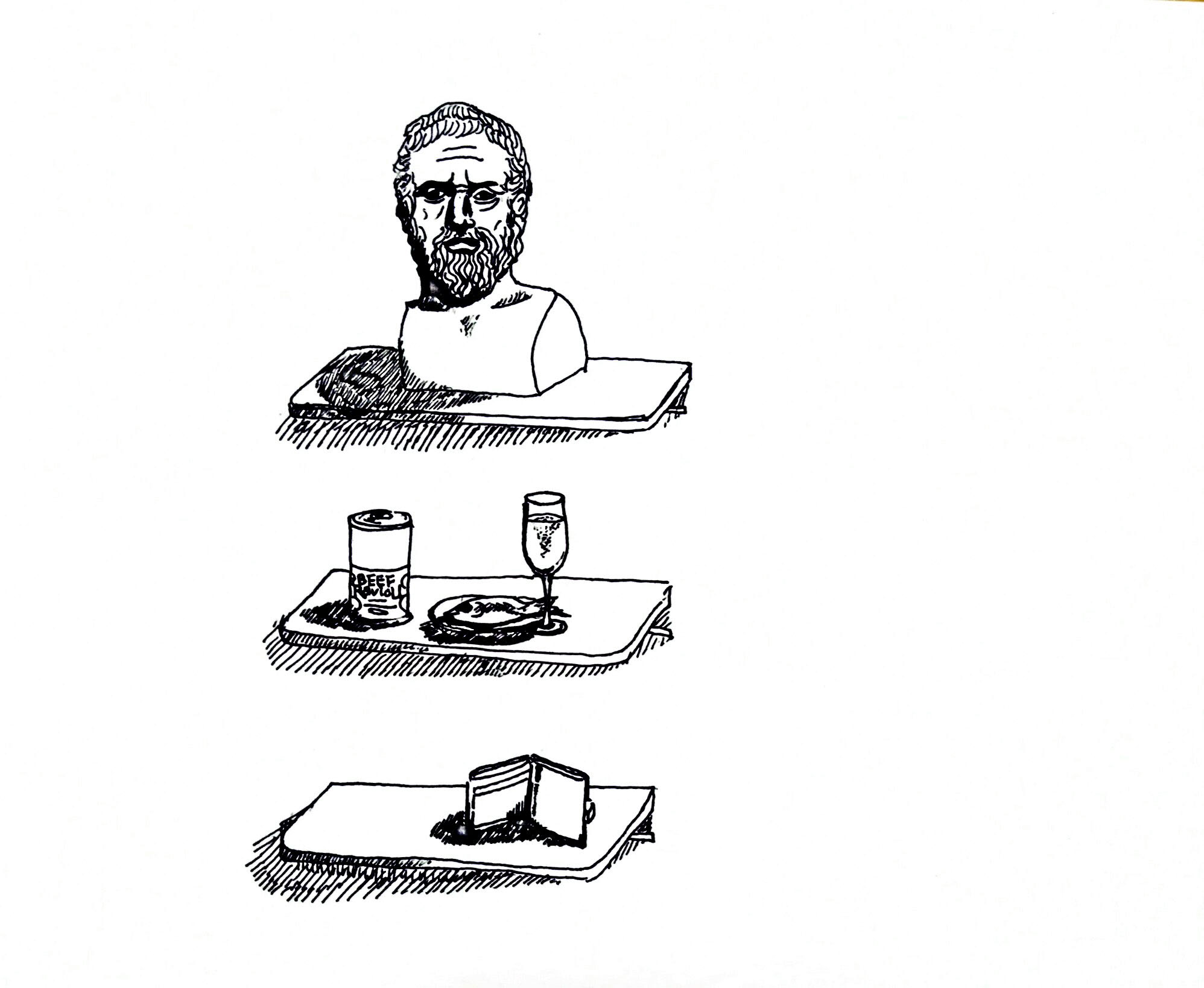

When it comes to spending the money he doesn’t save, Greco doesn’t give it much thought. This luxury is usually reserved for those who are either financially independent or saving enough each month to feel free to spend the rest on whatever they want. It’s also a benefit of having cheap tastes. He and his wife drive their parents’ old cars, cook meals at home (“with a 2-year-old and a half-year-old, eating out is pretty tricky”) and don’t often travel for leisure.

Like many thoughtful spenders, they also spend money to save time. “I feel like mostly my goal is to be in a spot where, given my tastes, which are simple, money isn’t the explanation for not doing something I’d like to be doing. For now, at least, that’s by and large where we’re at. We have a cleaning person who comes every week. That was an indulgence. We have two small children. So, we still have to clean a lot; it still gets bad. And we started doing Peapod for the convenience of not going to the grocery store.”

Overall, this behavior seems like something from a financial adviser’s fantasy. And the logic of it isn’t necessarily derived from philosophy, but certainly reflects Greco’s immersion in his area of expertise. “When it comes to epistemology, understanding what you don’t know is a big part of it. It’s understanding your limits — not just limits of your knowledge, but time — and trying to make decisions that are sensitive to that.”

Louis DeFelice is a junior in Jonathan Edwards College and the creator of the financial website wonderlearninvest.com. Contact him at louis.defelice@yale.edu .