Many composers are known for writing music on pianos. Composer Annea Lockwood is better known for burning them.

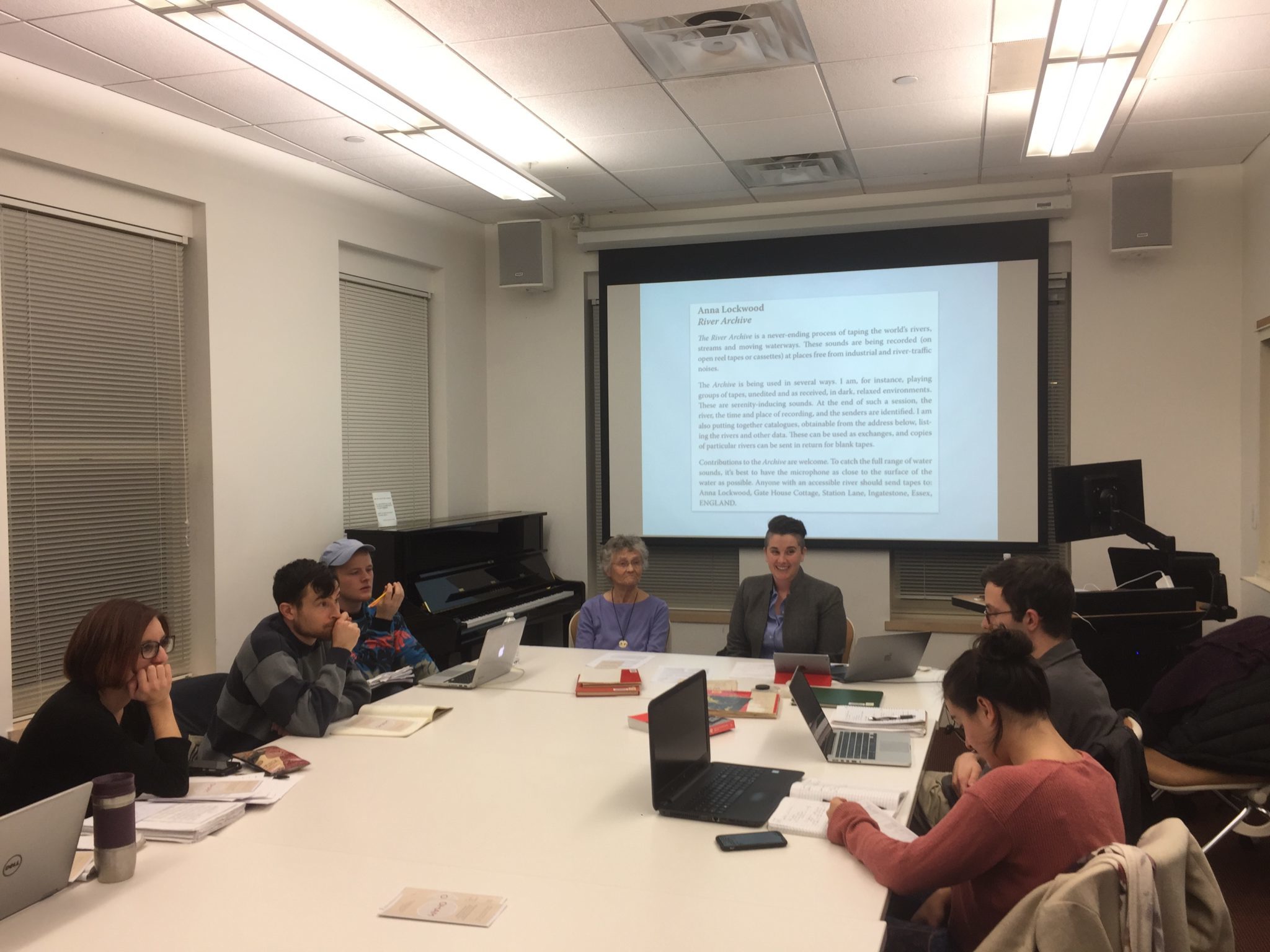

On Wednesday afternoon, Lockwood shared insights about her compositional process with students in Department of Music visiting lecturer Kerry O’Brien’s experimental music seminar, “American Experimental Music in the Long 1960s.” Throughout the semester, students study six collections of experimental music, concluding with the collection “Women’s Work,” co-edited by Lockwood and featuring the piece “Piano Burning.”

“It’s a rare opportunity to have a dialogue about this history with someone so plugged into this scene,” O’Brien said. “Lockwood can answer unique questions about these experimental music collections, including questions about the editing and selection process, the production and distribution of these scores and the connections and friendships that are reflected in collections like ‘Women’s Work.’”

Lockwood, who has taught music throughout her career, sees teaching as complementary to composing.

“Since a lot of my composition is focused on how we respond to sound, to be able to work on that and explore that with students has always been a real mind-opener,” Lockwood said.

Lockwood was classically trained in composition and piano performance, but since the 1960s, she has been known for her experimental style and her “close attention to sound,” according to O’Brien. For example, one of Lockwood’s works, titled “Glass Concert” and published in The Source magazine, lists 40 ways to produce sound from glass, including the technique of shaking a sheet of microglass.

Nicholas Serrambana ’20, a student in the seminar, said that because experimental music can sometimes seem “arbitrary and anonymous” when encountered only on the page of the score, the anecdotes and compositional thought processes Lockwood shared were a highlight of the visit.

O’Brien emphasized the importance of giving a female composer’s voice with the students.

“If you randomly ask someone in New Haven to name a composer, your responses will likely include Bach, Beethoven, Mozart or maybe Philip Glass if you’re lucky,” O’Brien said. “Almost always, people think first of white male composers, forgetting the works of women and people of color. Women, people of color, queer people … don’t often see themselves reflected in the histories that we study.”

O’Brien also said the title “Women’s Work” resists the implicit assumption that many historical musical works are the work of men.

During the seminar, Lockwood said the piece is about “strong women artists producing strong work.”

“It was powerful to listen to and speak with a female musical pioneer,” said Max Vinetz ’18, a student in the seminar. “Her presence in the class continuously inspired me to rethink the ways in which I should consume and participate in historical dialogues, as well as the manner in which figures are celebrated or otherwise forgotten.”

During the seminar, Lockwood shared a second version of the “Women’s Work” score, which is printed on a poster rather than in a book. Lockwood said of the poster, “You can hang it up on your wall, you can mail it to your friends, but it’s still a score.”

Lockwood was born in New Zealand and studied composition across Europe.

Julia Carabatsos | julia.carabatsos@yale.edu