Although the tax plan unveiled by Senate Republicans last Thursday differed significantly from the House’s proposal, one thing remains clear — higher education is on the minds of congressional Republicans.

While the House plan would effectively triple income taxes paid by Yale’s graduate students by removing a federal tax break on tuition reductions, the Senate plan upholds the current system, leaving that tax break untouched.

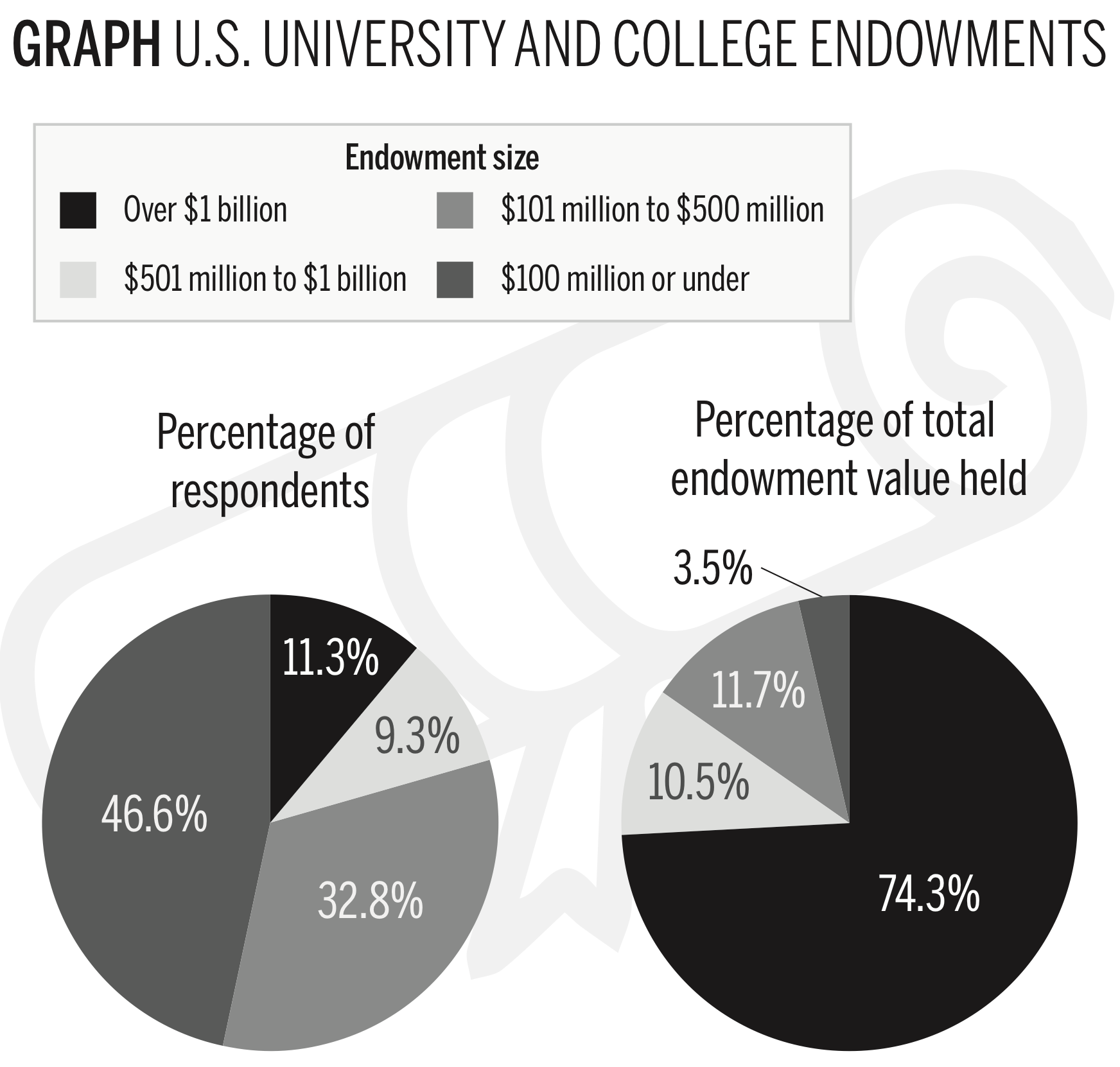

Instead, the plan would target large university endowments, imposing a 1.4 percent tax on endowment investment returns for universities with endowments worth more than $250,000 per student. This $250,000 bar is more than twice as high as that of the House’s plan, which proposes a 1.4 percent tax on endowment investment returns for universities with just $100,000 in endowment funds per student. Nevertheless, Yale, whose endowment amounts to about $2 million per student, would be subject to the tax under either plan.

Under the Senate plan, profits from licensing Yale’s name or logo to be featured on mugs, sportswear, flags and other products — all previously tax exempt thanks to Yale’s nonprofit status — would be counted as income unrelated to the organization’s core mission and thus subject to a tax.

Jorge Klor de Alva, president of the Nexus Research and Policy Center, which focuses on educational research, told the News that the Senate plan seemed to be more favorable for individual taxpayers because it placed more of the new tax burden on institutions, whereas the House plan targeted exemptions and liabilities for individuals to a greater extent.

“Both plans are targeting wealthy universities because that’s where the assumed unfairness lies,” Klor de Alva said. “That is, the colleges with large endowments are the ones hoarding money that could be better used from a public policy perspective.”

The Senate’s tax on endowment investment returns, with its $250,000 bar, would affect about 70 institutions nationwide, significantly fewer than the roughly 500 that would find themselves in the crosshairs of the House’s plan, according to Klor de Alva.

He said that the appearance of such a tax on endowment investment returns in both plans suggests that support within the Republican party for such a tax is strong and that some form of the tax is likely to pass.

Zachary Liscow LAW ’15, a professor at the Yale Law School who specializes in tax law and policy, said the tax on university endowments serves three purposes. Apart from raising revenue for the government, the tax would establish the principle that university endowment income is taxable, thus making it easier to increase the tax in the future. It would also send a message about the Congressional Republicans’ priorities, according to Liscow.

Mark Schneider, vice president at the American Institutes for Research, told the News that the motivation behind both chambers’ plans is less about raising tax revenue and more about sending a political message “that the concentration of so much wealth in so few institutions is contrary to the public interest.” He emphasized that the $200 million the tax would generate by his estimate is meager compared to the “grand scheme of the federal budget.”

Both Schneider and Norman Silber, a senior research scholar at Yale Law School and a professor at Hofstra Law School, said they support the Senate’s proposed tax on the sale and licensing of nonprofit organizations’ names and logos.

“If colleges are investing in profit-making businesses, why should those profits be exempt from taxation?” Schneider said. “Are T-shirts with logos core to higher education? I doubt it.”

Silber explained that the Senate proposal makes sense in most cases, because the profits that nonprofits reap from licensing their names and logos are not central to their missions. But he cited examples, like the use of pink ribbons to raise awareness of breast cancer, in which such logos do promote the core interests of nonprofits, and suggested a “balancing approach.”

Still, he admitted that, in the case of universities, logos and names are mostly used to sell merchandise unrelated to the institutions’ core mission.

“It’s a little different when you are talking about a university’s logo, like the Bulldogs,” Silber said. “It’s not advancing the educational mission. It’s more like selling the school.”

The Yale Bookstore sells 16 ounce coffee mugs emblazoned with the Yale logo for $12.98.

Jingyi Cui | jingyi.cui@yale.edu