On an unseasonably cold day in New Haven almost a century ago, the star diver of Yale’s class of 1928 performed his last jump off the diving board and into the clear water of a varsity swimming pool. The only son of the Vandercook family of Connecticut, Willard Elmer Vandercook, Jr. was on track to receive his degree in Engineering from Yale, building on a family legacy large enough to fill every room of their three-story home on Franklin Street in the nearby town of Ansonia. Waiting for him at home were his mother, Alice; his father, Willard Elmer Vandercook, Sr.; and a younger sister, Irene. Then, there were the boarders: a family from Cuba of Spanish descent who in 1917 took residence in one of the extra rooms of the Vandercook home: an enterprising engineer and ex-seminarian similar to the youngest Vandercook in age and profession named Joaquin López-Díaz; his wife, Teresa Sanz; and their infant daughter, Adolfina — my grandmother. The Vandercook family planted the seeds of home in America for my family long before our lives here became permanent.

Willard emerged from the pool with a fatal neck injury. I thought of him from time to time on my walks to class at Yale — of how maybe, in some cosmic sense, he led me here, too. He died later that day. This was the end of the Vandercook line (as far as we knew, at least), and the beginning of a story of familial exceptionalism passed down in my family. But the Vandercook story, I would learn, is much less linear than I thought.

At the end of each new detail, I found a new Vandercook family — more foreign to me, yet nearer, than the last.

***

On a seasonably cold afternoon in March 2016, Adolfina Shirko-Fernández spilled Dunkin Donuts coffee on herself and the car upholstery as I tried to determine a route from Yale to 75 Franklin St., Ansonia. Resting only on the semi-reliable testimony of what trees and road signs looked familiar from her brief visit to the house the previous fall, I wondered if the trip out to a town I had never heard of before that weekend could serve for anything more than my mother’s vague recollection of her grandfather’s brief years in Connecticut.

Thirty minutes and several wrong turns later, we parked too confidently on the swale in front of a three-story pale yellow clapboard house. Next to the door were three iron mailboxes, some with names scratched out, and others with Eastern European or Hispanic last names, not a single Vandercook among them. None of the neighbors had ever heard that name.

***

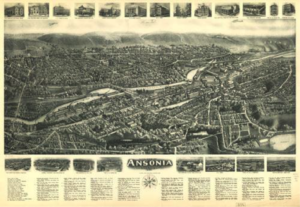

Map of Ansonia, CT, 1921.

On his morning walks to work at the Farrel Foundry & Machine Company from the Vandercook home in 1917, 25-year-old Joaquin López-Díaz saw the sun rise over the Naugatuck River from the sloping hill of Franklin Street, past innumerable elms of every hue, colors and fauna he had never before seen in his home of Matanzas, Cuba. He had only been in the United States for two years, having moved to America to study engineering after running away from seminary in Cuba. Farrel specialized in the manufacturing of iron and steel parts for factories, including sugar refineries in Cuba. The head of the Vandercook home, Willard Elmer Vandercook, worked in management at the nearby S.O. & C. Company on Canal Street, specializing in eyelet machinery. He, a descendant of Dutch Albany, New York, settled in the Copper City of the Naugatuck River valley in the 1880s as a follower of an industrial manifest destiny.

Joaquin met Teresa Sanz Rodriguez of Holguín, Cuba in 1914, only a year before he left Cuba. In 1917, thousands of miles away, he proposed marriage to her in a letter. They were married by proxy, and a few months later, Teresa joined Joaquin in Pennsylvania, after a three-year separation, as his wife.

The next year, Teresa gave birth to their daughter Adolfina López at Grace Hospital in New Haven. When Joaquin worked at Farrel, Teresa had the help of the Vandercook women at home: Alice, the matriarch of the house, an Irish immigrant; and her 14-year-old daughter Irene, who babysat Adolfina for the four years the Lópezes lived with the Vandercooks.

Joaquin, Teresa, & Adolfina López with Alice & Willard Elmer Vandercook in Ansonia.

Juan Joaquin López-Sanz, Joaquin’s fourth child, was born in 1932 in Matanzas, long after his parents and older sister had left Connecticut to return to the island in 1921. Until his passing in March, Joaquinito lived alone in Auburn, Alabama. In Cuba, he served nine out of a 20-year sentence for attempting to leave the country illegally, after which the authorities allowed him to go.

After those years of isolation, Joaquinito devoted his adulthood to intellectual life, cataloguing our family’s history into neatly composed Word documents. In the 2009 document titled “Joaquin López-Díaz,” he writes of his father’s life living in the Vandercooks’ “very large house” at 75 Franklin and working in the country Joaquinito spent years in prison trying to reach.

“Really, they went to live as though they were part of this family, who were Jewish, and had a painful emotional situation due to that their only son, athlete and star swimmer of Yale University, broke his neck and passed away in one of his trampoline jumps in a pool of said University.” The Lópezes would turn the coals in the furnace for the Vandercooks on the Sabbath (I later learned they were parishioners at Christ Episcopal Church, but Joaquinito was resolute.)

Joaquinito visiting 75 Franklin St., Ansonia in 1992.

My mother remembers her grandfather Joaquin’s life in Connecticut by the bravery his journey symbolized for the family. “He wasn’t afraid of anything.” Teresa often said, years later: “Los Americanos son mi pelota” — Americans are my ball, feeling much like a child with a favorite toy toward her American friends, the Vandercooks. “All my life, I remember my mother and grandmother singing Home sweet home, there’s no place like de home … all those songs from America in the ’20s.”

She remembers taking trips when she was a child in the 1950s to see the Vandercooks in Ansonia. After the Lópezes left the house on Franklin St., Mrs. Vandercook and her daughter Irene stayed in close contact with Teresa and Adolfina, always writing letters to Cuba and back. “Even after my mom died, [Irene] got in contact with our family,” she recalls. Irene lived the longest of them all, passing away in 1990; her letters to my grandmother are likely lost somewhere in a relative’s home in Cuba. “My mother and grandmother always talked about the Vandercooks, because they treated us like family, not like tenants. They were always so welcoming, la verdad.”

***

The next time my mother and I visited Franklin Street, my aunt came along for the ride. As we exited off 34 and onto Ansonia’s Main Street in late September, the elms that managed to keep their green looked black under an overcast sky. “It doesn’t really look like it’s thriving,” commented my aunt for no reason but to cut the silence in the car and the distance since her last visit. When I knocked on the door of third-floor apartment of 75 Franklin St., asking for the Vandercooks, a woman through the slim crack of the door said: “I’ve never heard of them before, and I’ve lived here for years.”

Unsatisfied that so rich a history could be lost within the shadowy auspices of that yellow house, I turned to what I hoped would be impeccable records at Yale’s Manuscripts and Archives in Sterling Memorial Library. If I could find Willard, then I would find our story. Why should this illustrious engineer’s life and career have been cut short? Who was this man so influential to our family we lost him? But after poring through every page of the 1928 Yale Banner and accompanying class book — a relic of a time when the University’s much smaller class allowed it to lavish each student with a personal biography — I couldn’t find Willard anywhere. Not in the many pages devoted to Athletics or Senior Societies. Not on the Varsity Swim Team. It was as if neither he, nor the Vandercooks, ever existed.

Willard E. Vandercook, Jr.

Then, I found a very different Willard Elmer Vandercook, Jr. in the far less ivy-crusted pages of the class of 1928S, the class book of Yale’s recently absorbed Sheffield Scientific School. It states that “Van” took the general science course, and took a semester off. He was a scholarship student, absent from academic honor societies, and graduated without distinction.

Van’s yearbook photo.

The biography ends: “Van plans to take up time study work after graduating from Yale. His permanent address is 65 Franklin St., Ansonia, Conn.”

65. Sesenta-y-cinco in Spanish, just a consonant away from setenta-y-cinco — 75. One syllable took my family on three trips to the wrong side of Franklin Street. I thought of the yellow house and the strangers I met there. I thought of Alice Atchison Vandercook, no less a stranger in this country than Joaquin and Teresa.

After all this time, which other details had we misinterpreted, marred by time and memory?

***

When I drive into Ansonia the week after my discovery, it is unseasonably warm, and the sun on Main Street shines in defiance of late October. The two signature smokestacks of the now dilapidated Farrel Corporation building stand tall over a town waning from its illustrious past.

On the intersection of Main and Bridge streets, a mural of the same intersection 100 years ago, illuminated by an opera theatre marquis and the headlights of old Fords, towers over dollar stores, takeout restaurants, and church buildings with “FOR RENT” signs. City Hall and a handful of other stately buildings look like monopoly houses dropped precariously onto the quiet landscape.

I park my car in front of 65 Franklin St. While I search for the house number behind obstructive elms, a white-haired man in a deep blue Patagonia sweater approaches me warily.

“Can I help you?” he asks me.

I tell him my story and that surname, unsure anymore of what I am hoping to learn about this place.

“Ms. Vandercook was my second grade teacher!”

Karl King has lived in Ansonia all his life. His brother-in-law bought the one-family house in 1984, expanded it to a two-family house, and sold it to Karl in 1991, where he and his wife Nancy have lived for 26 years. He was born at Grace Hospital, just like my grandmother.

I ask Karl how he has seen Ansonia change in his lifetime. He says, “It went through so many changes. But there’s no more manufacturing.” In the decades after the second world war, changes in manufacturing technology and the rise of synthetic materials for piping and tubing spurred the decline of Ansonia’s metal industry.

“You had Farrel’s, and you had American Brass. You had two big factories in this town, one right on the side of the other. That’s what built Ansonia. If it wasn’t for the factories, it would probably be a rural town.” With generators powered by the Naugatuck River, factories like these up and down the Valley gave their respective towns a national product-based identity. “Ansonia was known as the Copper City…Waterbury was the brass city, Danbury was the hat city, because Stetson hats started in Danbury.”

These factories provided jobs for thousands of immigrants from Ireland, Poland, Russia, Italy — and at least one from Cuba. “You could be unskilled, but you could have a well-paying job. I knew so many people in Ansonia, older guys, that bought a house, sent one or two kids to college, and the wife never worked.” As of six years ago, American Brass ceased operations, and no manufacturing occurs at the old Farrel factory. “Not that I’m the smartest guy in the world, but I’m pretty good at forecasting things,” he shared. “I just knew that wasn’t gonna last.” On economic growth since then, Karl remarks shortly, “We have a Target in Ansonia now.”

Karl was Irene’s second grade student at the now abandoned Peck School, only a couple blocks from Franklin Street, in 1959. “Everybody loved Ms. Vandercook,” he recalls fondly. He remembers her blue 1957 Chevy she drove to school, and though she never married, her love for life was reflected in the small joys she entertained.

Now, at 65, Karl works part time at his cousin’s funeral home down the street and takes pleasure in keeping up his yard. He shows me today’s arrangement: an array of lively Halloween decorations on the back porch, where a small hill slopes serenely. It looks familiar.

I remember the flags in the window of what was one hundred years ago, in architecture and in kinship, a one-family home. I show Karl a picture of Willard that Joaquinito sent me. “I think that’s from the side, comin’ up the driveway!” he says. I am standing where it was taken.

At the end of our conversation, I mention Van. “I thought you were going to say this house is haunted!” Karl laughs. Like every other legend, this depends on who you ask.

***

On August 5, 1937, second-generation-American son Willard Elmer Vandercook, Jr. left this world with late summer in the clear water of the Atlantic. After graduating from Yale, his class’ alumni book says he found jobs in industrial engineering in Boston, Savannah, and Baltimore. He was never a star diver or fabulously wealthy. He was survived by his widow, Margaret Ann Johnston; his son, Peter John; and his daughter, Susan Gerry Vandercook Bishop, who lives in Glastonbury.

When I call the number listed for “Gerrie V. Bishop” in the WhitePages, I hear a man’s voice on the answering machine telling me, “We’re not home right now.” While I hope “we” means anyone who remembers this story, I receive a call back, and it’s her: “I got your message, and I just want to let you know I’m the person you’re looking for.”

“Go home with your mother before the baby is born, and I’ll call you when I get back.” These were some of Gerrie’s father’s last words to her mother Margaret, spoken over the telephone from Savannah, Georgia on a business trip in 1935. The baby was Gerrie, who never got to meet her father. Van had taken a boating trip with friends on the Atlantic (“gives you more time with your mom,” Van proposed to Margaret). Regarding the fateful dive, Gerrie tells me “nobody ever knew what happened.” He hit his head, the story goes, but Gerrie explains he had been bald at the time, and there was no scar. More likely, his collarbone received the brunt of impact. At the hospital, he spoke to his wife briefly, before he went into a coma, and passed that night. “Her life’s dream was to marry my father and have four children. He was going to make it as an industrial engineer so she could devote herself to her husband and to her four children,” Gerrie shares with me. “When my father died, she was devastated. Everything changed.”

Margaret & Van, 1930s.

Gerrie insists that she knows nothing about her father, but the way she speaks about him indicates an intangible memory. “[My mother] told me I have his personality. He could step on a train and talk to everybody,” Gerrie told me, about forty-five minutes into her phone conversation with a total stranger.

Margaret remarried a year later, but she never stopped loving Van. “He was the love of her life,” Gerrie recalls. The Vandercook women never forgave Margaret for remarrying. Perhaps this is why Irene never married — to atone for the imprudent remarriage of her sister-and-law.

They did, however, let Margaret and the kids visit. Gerrie remembers Irene’s homegrown tomato-and-onion sandwiches, Alice’s Northern Irish “ultra-protestantism,” and their warm, yet formal, love. “Every year they’d give me a piece of sterling silver. Dear Susan, they would always write me; they would never accept that my father named me Gerrie — like the drink, Tom & Jerry!” Alice and Irene remained inseparable until Alice passed at 102 years old. “Grandma was always kind to children, always. That kind of thing is what kept them going. Otherwise, they were isolated.”

Gerrie, in turn, took care of Irene when she grew old. And so the Vandercook women went quietly into the frame of that old house.

Gerrie, my last link to this family’s small world, wishes she could have known her grandmother and aunt better, despite their complicated relationship. After a healthy career, marriage to the love of her life, and the loss of her husband last year, Gerrie remains resilient. “After all the pain and suffering in between, I can’t complain.”

***

As I walk through the paths of Pine Grove Cemetery at the end of my journey, leaves crunching below my feet and the rising sun, I think of engineers. I think of average men immortalized in Romantic legends, and of the twenty-three years it took Willard Sr. to pay off a $2,000 mortgage on the house at 65 Franklin St. to the Derby Savings Bank in 1935, the year he died. I think of all the snow absent from today that I saw in the old photographs Joaquinito sent me and of Van, Irene, and Joaquin sledding in the backyard. I think of the yellow house that misled us, of Joaquin’s death after the rise of the Castro regime, and of Joaquinito’s quiet passing this March. I think of quiet nights by the stove in conversations I’ll never hear, of women from opposite sides of the world cooking and singing together.

At the Vandercook graves, we are reintroduced to one another in the morning light. It is possible I would never have come to Connecticut if it weren’t for their anonymous gift. I flip back to the epigraph of the 1928 Yale Banner.

The crystal sphere with magic powers

Will tell the tale of future hours;

Of fame and fortune, love and hate,

Of death and life, unerring fate.

But Memory, in subtle way,

Can light the heart as bright as day:

The pages here contain the key

Of secrets, known to Memory.