Art inherently has incredible redemptive and didactic power. Live theater suspends reality for a brief period, allowing audience members to entertain multiple controlled versions. “Outside Wednesday Night at Toad’s” is an original play written by Zulfiqar Mannan ’20, a staff reporter for the News, that I am directing this semester. The play takes advantage of live theater’s ability to productively open dialogue about mental health at Yale. It does so by discussing, quite candidly, the intricate, often-invisible ways that Yale’s culture can augment pre-existing depressive and anxious tendencies or disorders in students.

We spend our four years here learning to critique the world at large, sometimes forgetting to hold campus culture to the same standard that we do the one outside. The social structures that govern the world and the complexities and prejudices that result from them find a home here but are conveniently repacked to render them socially acceptable. The trickle down of racism, sexism, homophobia and xenophobia can be so subtle that students often have trouble placing what, precisely, is making them uncomfortable, even isolated, in the place sold to us as an intellectual utopia. As a defense mechanism, some students remain silent, wondering if they themselves are crazy for finding fault in what everyone around them seems to benefit from. This kind of reckoning is much more prevalent than many care to admit and more quietly insidious that many give it credit for. Our silence has a body count.

“Outside Wednesday Night at Toad’s” explicitly criticizes Yale for reflecting the very systems that so many students commit to dismantling on paper, to employers and to themselves. The play holds larger systems of power accountable for their role in mental illness. It does so through the narrative of a first year who commits suicide.

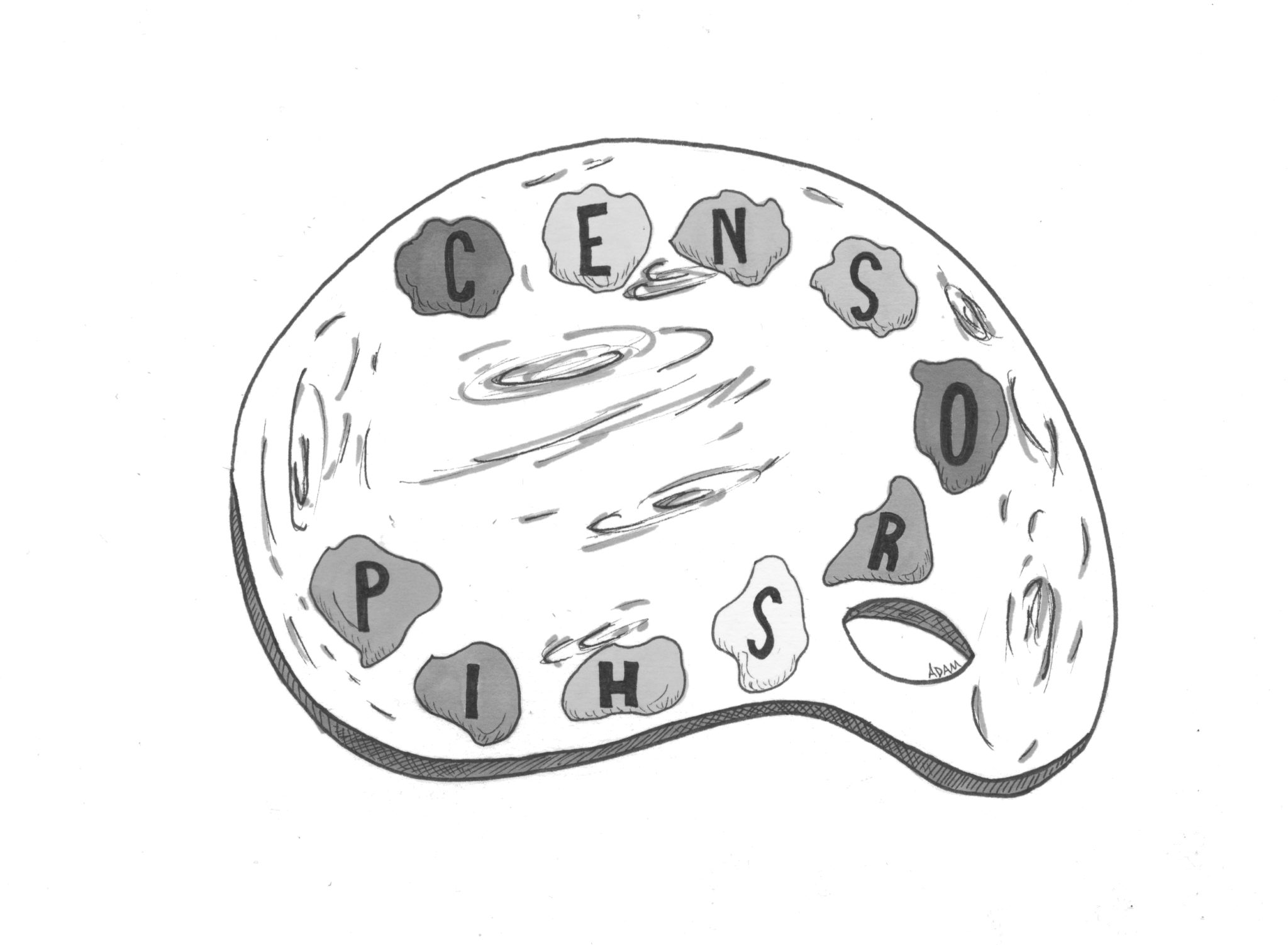

Some responses to the play have been skeptical. Some feel it is simply “too much” because of its subtitle: “A suicide in two acts.” Some doubt the grounds that the author and I have to present this subject matter to Yale. Many doubt the productive value of bringing an issue as delicate and intense as suicide to Yale’s stages. This sort of questioning is justified, expected and necessary in that it provides an opportunity for conversation. But backlash that intends to shut down art before it is presented is unproductive and has no place in Yale’s art scene.

Theater specifically provides a unique forum in which we must thoughtfully discuss mental health. Good theater stretches the capacities of our imagination and empathy. Bad theater triggers the audience. I have seen my fair share of bad theater, both on Yale’s campus and off, and understand the implications and risks of a play about mental health directed or written tactlessly. To be sure, fearless art does not mean reckless art.

“Outside Wednesday Night at Toad’s” was written from inception to end with the desire to dispel myths about the emotional toll mental health struggles can take while providing a sense of catharsis to its audience. As someone who deals with depression and anxiety and has experienced suicidal thoughts, I personally attest to the artistic and redemptive worth of this play. But I also advise anyone who remains hesitant about the subject matter, who suffers from mental illness or who is personally affected by the issues the play seeks to unpack to take the play’s trigger warnings seriously, to reach out to a mental health professional before seeing this play, to enter with the understanding that they can leave at any point.

I hope that the audience finds solace and solidarity with the characters in “Outside Wednesday Night at Toad’s.” This play, in all its honesty, poetry and pain, calls attention to a culture that condones mangled forms of systematic racism, sexism and homophobia. It holds these factors accountable for the damage they have already done while warning against their continuation. It speaks a truth that will feel recognizable to Yale’s student body and beyond. I urge Yale’s campus to deal with the stains that marginalization and silencing leaves on the mental health of its student body, perhaps for the first time.

Casey Odesser is a sophomore in Jonathan Edwards College. Contact her at casey.odesser@yale.edu .