We humans draw lines on maps, setting up boundaries of states, counties, private lands and national parks. But what do these demarcations mean for animals? A temporary exhibition about migration at the Peabody Museum sets out to explore this question.

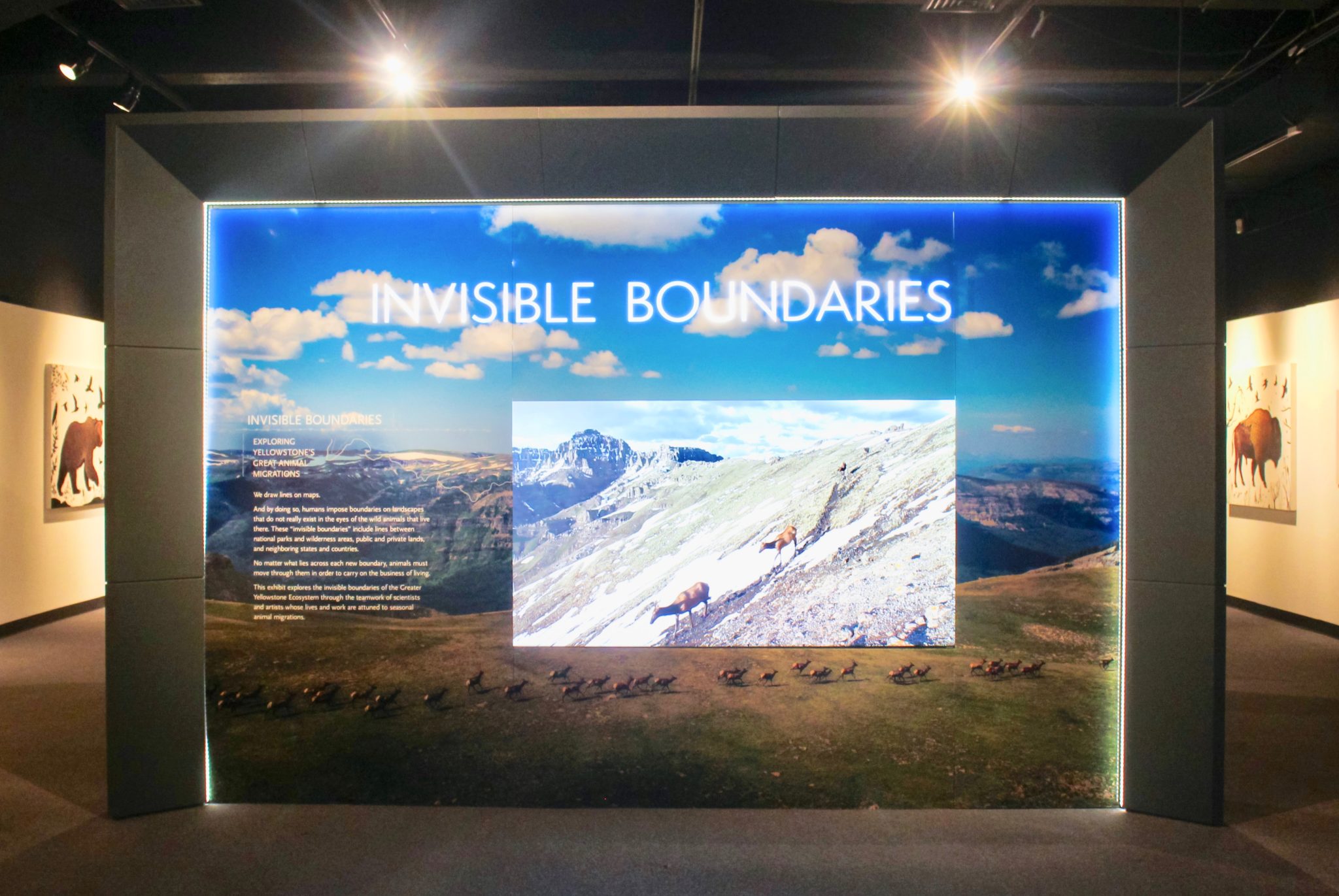

Aptly named “Invisible Boundaries,” the exhibition explores wildlife migration across human-imposed boundaries that are invisible to animals, in particular elk migration in the greater Yellowstone National Park area.

“The message of the exhibit is that these boundaries can cause big issues for wildlife that straddles inside and outside the boundaries,” said David Skelly, an ecology professor and director of the Peabody Museum.

At the center of the exhibition room on the first floor is an interactive 3-D map of elks’ seasonal migration patterns, compiled with data from years of tracking studies done by ecologist Arthur Middleton FES ’07. Circled by display boards detailing their interaction with the local ecosystem and potential solutions to human impact, the map highlights the central theme of the exhibition: We may draw up lines for Yellowstone National Park, but elks constantly have to travel in and out of those boundaries to survive.

But the exhibition is not just about hard science. Lined up outside, photographs taken by National Geographic Photography Fellow Joe Riis range from aerial views of the entire herd to close-ups of a single elk, and paintings by James Prosek ’97 dot the entire room, extending the focus beyond elk migration to the larger human-animal relationship. Visitors can also view a short video produced by filmmaker Jenny Nichols.

This project represents the interdisciplinary work of Middleton, Riis, Prosek and Nichols, who trekked in Yellowstone to study elk behavior.

Although the team began working for the exhibition in 2013, Middleton has been studying the Yellowstone ecosystem for about 10 years. The inspiration for the project, he said, was to engage the public in conservation.

“All the stories I had seen about migration were about how beautiful and inspiring they are, but as an ecologist, I thought the missing part of the story was how important they are to the ecosystem,” Middleton said. “I thought we could really tell a bigger story.”

The Buffalo Bill Center of the West sponsored the exhibition through the Camp Monaco Prize grant, which provided funding for collaborations between scientists and artists. Middleton said he appreciated Riis’ previous work in the nearby areas, so he approached Riis about the possibility of working together and collaborated on the grant application.

Later they also enlisted the help of Prosek, whom Middleton met as a postdoctoral fellow at Yale. According to Middleton, Prosek was writing a book at the time and asked to join their trip to Yellowstone.

“While we were talking about the elk, he kept pointing to birds in the trees that were visitors from the tropic,” Middleton said. “We thought James could provide a broader perspective … beyond what data and photographs can capture, and we asked if he would collaborate.”

Aside from their original work, the exhibition also features documents from the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library on the history of the Yellowstone National Park, the first national park in the United States, Skelly said.

Five visitors interviewed all gave the exhibition positive reviews. Glenna Silk, who attended as part of a school project, said that she especially liked the photograph depicting an elk crossing under a barbed wire fence, which had been adjusted to allow for animal crossing.

“That really tied it back to the ‘invisible boundary’ theme,” she said.

Each year, the Peabody Museum presents two or three temporary exhibitions, including another one about the art of Al Gilbert that is currently on display on the third floor, Skelly said.

The exhibition will be on display through March 25, 2018.

Malcom Tang | jiawei.tang@yale.edu