The public’s perception of homelessness has changed over the past two decades to become more compassionate and liberal, according to a recent Yale study.

Using an online platform, Yale researchers surveyed Americans on their attitudes about homelessness and then compared the results to studies from the 1990s. The new study found that Americans are now more likely than they were 20 years ago to attribute homelessness to external factors like the economy, rather than internal factors such as laziness or irresponsible behavior. Americans surveyed also showed significantly more support for affordable housing and government funding to end homelessness. The study, which was the first to examine public attitudes about homelessness in more than 15 years, was published on Oct. 13 in the American Journal of Community Psychology.

“A lot of services for homeless people are funded by public dollars, so [funding] really depends on how supportive the public is,” said Jack Tsai, lead author of the study and professor of psychiatry at the Yale School of Medicine. “We thought that at some point [support] would plateau, but there seemed to be even more support than two decades ago.”

For the study, 541 survey participants answered 26 questions to gauge their attitudes and beliefs about homelessness on a scale of 0 to 4. The questions were identical to those used for two previous studies in 1992 and 1995.

The largest changes in attitude were increases in support for homeless people’s right to sleep, take shelter and panhandle in public spaces. If other studies come to similar conclusions, the results would show legislators that the “public still cares about the homeless” and supports legislation to help them, Tsai said.

According to Tsai, public perception may have been influenced by major initiatives in the past two decades to address homelessness, such as the Bush administration’s 10-year plan to combat homelessness and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs’ efforts on behalf of the homeless veteran population.

The 2007–09 economic recession may have also contributed to the public’s shift toward more liberal attitudes, Tsai said, as most Americans were either affected or knew people who were negatively affected by the recession. People are more likely to show compassion for the homeless after experiencing economic hardships themselves, he said.

According to Sarah Fox, director of advocacy and community impact at the Connecticut Coalition to End Homelessness, Connecticut is a “leader in the nation in our efforts to end homelessness.” Connecticut was the first state to end chronic veteran homelessness in 2015, and it is on track to end chronic homelessness.

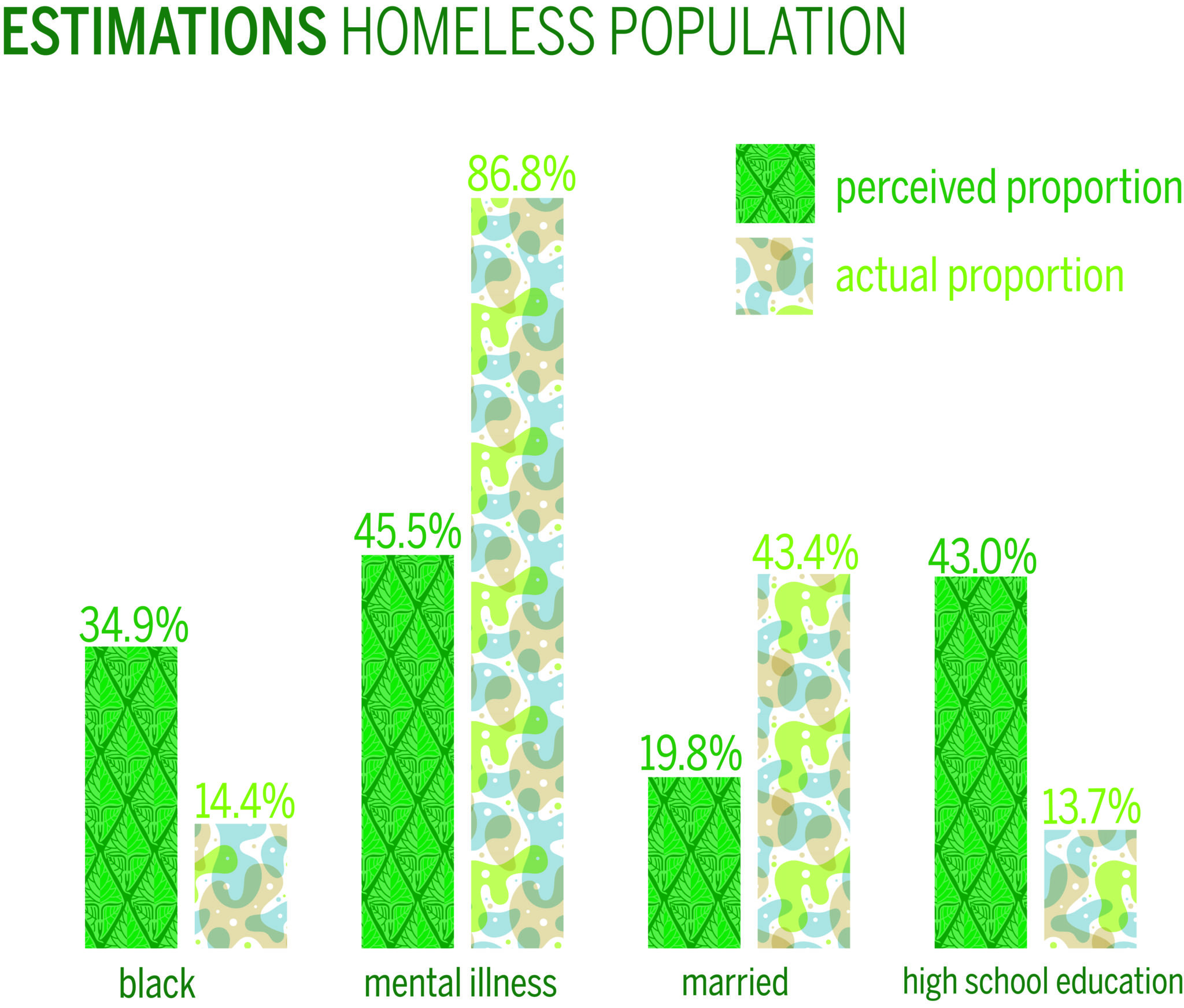

The study also found that the public’s perception of the demographics of homeless people greatly varies from the actual population. While subjects estimated that 34.9 percent of the homeless population is black, the actual proportion is 14.4 percent, according to the 2012–13 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. In addition, surveyed Americans estimated that 45.5 percent of homeless people have a mental illness and 19.8 percent are married, while in reality, the proportions are about 86.8 percent and 43.3 percent, respectively.

According to Tsai, the results suggest that the general public is not aware that a significant proportion of the homeless population are older, uneducated and white, and that many homeless people have families and suffer from substance abuse and mental health problems.

“People generally develop stereotypes or caricatures of who homeless people are even if that population changes,” Tsai said. “The stereotypical image of a homeless old man has changed somewhat.”

Serena Tharakan ’18 and Jackson Willis ’19, co-presidents of the Yale Hunger and Homeless Action Project, both said they could not generalize Yale students’ attitudes about homelessness, just as they cannot make generalizations about the homeless population.

Tsai said that New Haven has a relatively large homeless population for a city of its size, but the city “tries to accommodate them the best they can” through support services. According to the Connecticut Coalition to End Homelessness’ 2017 Point-in-Time survey — a survey conducted on one night every year — New Haven’s homeless population dropped from 730 to 543 since last year.

While people in New Haven have become more knowledgeable of the homeless population’s needs over the past two decades, some people still misunderstand the homeless and have an “irrational fear of poverty,” according to Alison Cunningham, CEO of Columbus House, a local nonprofit that provides housing and support services to the homeless.

In recent years, Cunningham added, organizations have been working more collaboratively with local hospitals, police, housing services and Connecticut children’s support services to address homelessness. Service providers are “constantly changing and growing as we come to understand the people we’re serving,” she said.

Tharakan agreed that many different types of local community groups support homeless individuals in New Haven, and she emphasized that these organizations are powerful and exist independently of Yale.

“We’re here for four years, and there are people who devote their whole lives to this,” she said.

In the state of Connecticut, the homeless population decreased by 13 percent from last year and by 24 percent from 2007, according to the Connecticut Coalition to End Homelessness.

Alice Park | alice.park@yale.edu