Soon, rather than visiting the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History in per- son, anyone will be able to access 3D scans of the Peabody’s vertebrate collection at no cost from the comfort of their homes.

The Peabody, along with 16 other U.S. museums and universities, is taking part in the creation of a digital vertebrate encyclopedia, called “Open Exploration of Vertebrate Diversity in 3D,” or oVert. The project is funded by a $2.5 million grant from the National Science Foundation.

“Understanding structure is the key to understanding everything about an organism,” said Bhart-Anjan Bhullar ’05, co-principal investigator on the grant and an assistant curator in Yale’s Department of Geology and Geophysics.

The purpose of the oVert initiative is to unite public museums and universities in compiling their collections of vertebrates into an online database, said David Skelly, the director of the Peabody.

The initiative, which will start the first week of November, will create digital and open-access entries for noninvasive CT scans of 30,000 vertebrate species, said Greg Watkins-Colwell, the lead principal investigator for the Peabody’s part of the initiative.

One of the major benefits of the CT scan technology is the ability to leave the organisms intact.

“Before, you had to dissect the organ- isms, so the tissues didn’t remain in place,” Bhullar said. Scanning the specimens will allow all their structures to stay the same, he said, which may o er opportunities for new discoveries about the functions of various structures.

The Peabody does not have the machinery necessary to perform these scans, but will send the specimens in the collection to Harvard, one of the six regional scanning centers. Approximately 1,000 of the specimens sent to the scanning centers will be contrast-stained, so that soft-tis- sues will be visible using the computed tomography scanning technology. This contrast staining enables detailed 3D imaging of not just skeletal systems, but

also organ systems, like the nervous and digestive system.

According to Bhullar, these soft-tissue scanning techniques will allow researchers to study evolution in structures outside the skeleton, including the brain.

The precursor to oVert was a program called iDigBio, which was an initiative to support the digitization of museum collections worldwide, said Watkins-Col- well, who also manages the collections for herpetology and ichthyology in Pea- body’s Department of Vertebrate Zoology. He added that although iDigBio enabled access to data on thousands of species, it was missing a critical component — detailed anatomical images of vertebrates.

The new digital project is government-funded, which means that the platform will be available to the public for free, Bhullar said.

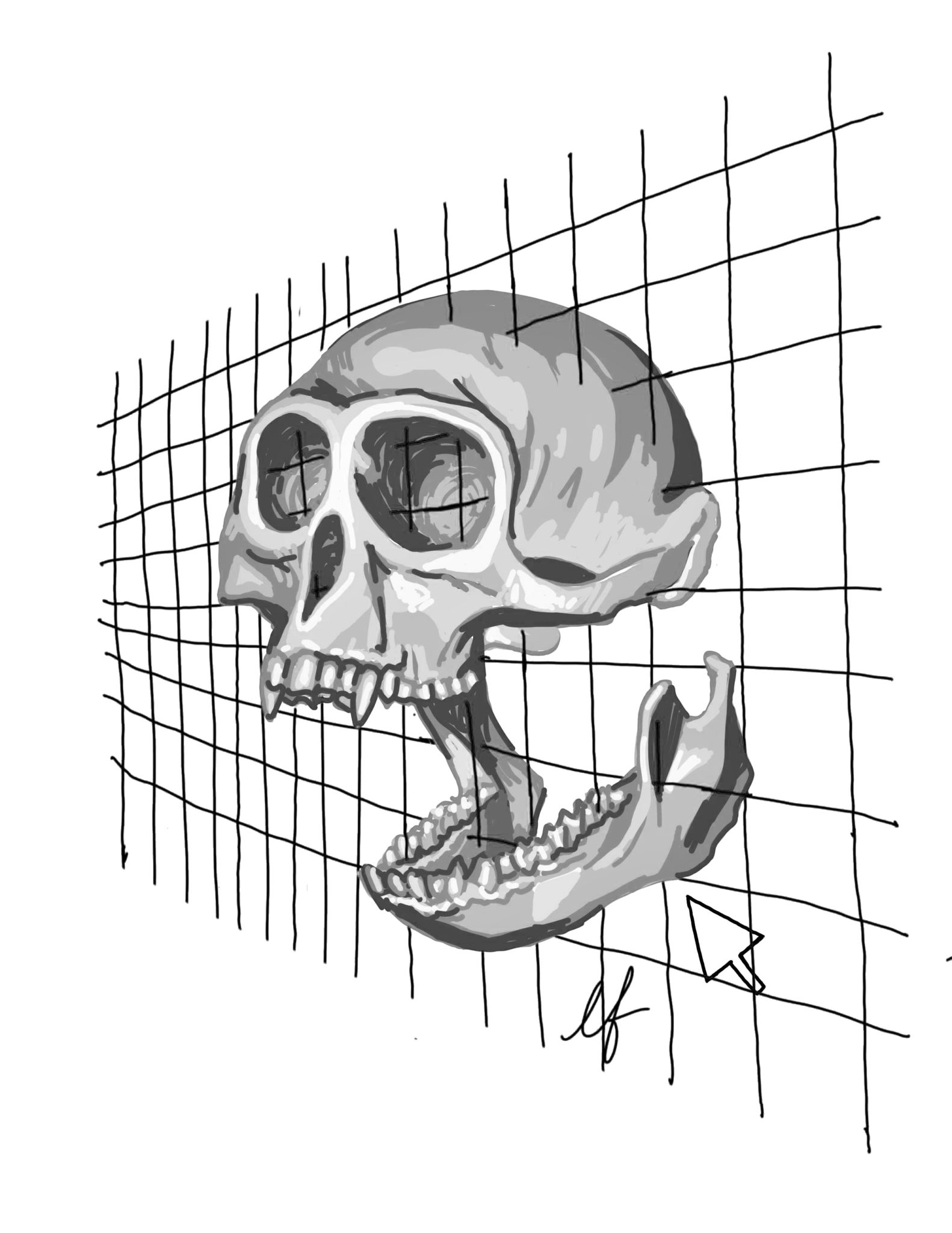

“So much is inspired by the exquisite machines present in various organisms,” Bhullar said, adding that the initiative has the potential to be used in fields like edu- cation, research and even art.

For example, a kindergarten teacher could 3D print a baby whale skeleton for a lesson, or an animator could use a scan of a lizard for reference in drawing the muscles of a dragon, Watkins-Colwell said.

Because of the high price of scans, no one has attempted this type of initiative until now, he said. As the technology has become more available, universities and museums have become more inclined to scan their collections. According to Bhullar, Yale will even have a computed tomography scanner by next semester.

The oVert initiative appears to be an example of the future of museums, Skelly said. People across the globe will have access to data kept in museums even if they do not have direct access to the museum.

“It’s going to be a fabulous research resource,” Skelly said. “[We] can’t even imagine all the ways it’s going to be used.”

The Peabody’s overall collection encompasses more than 13 million speci- mens and objects.

Madison Mahoney | madison.mahoney@yale.edu