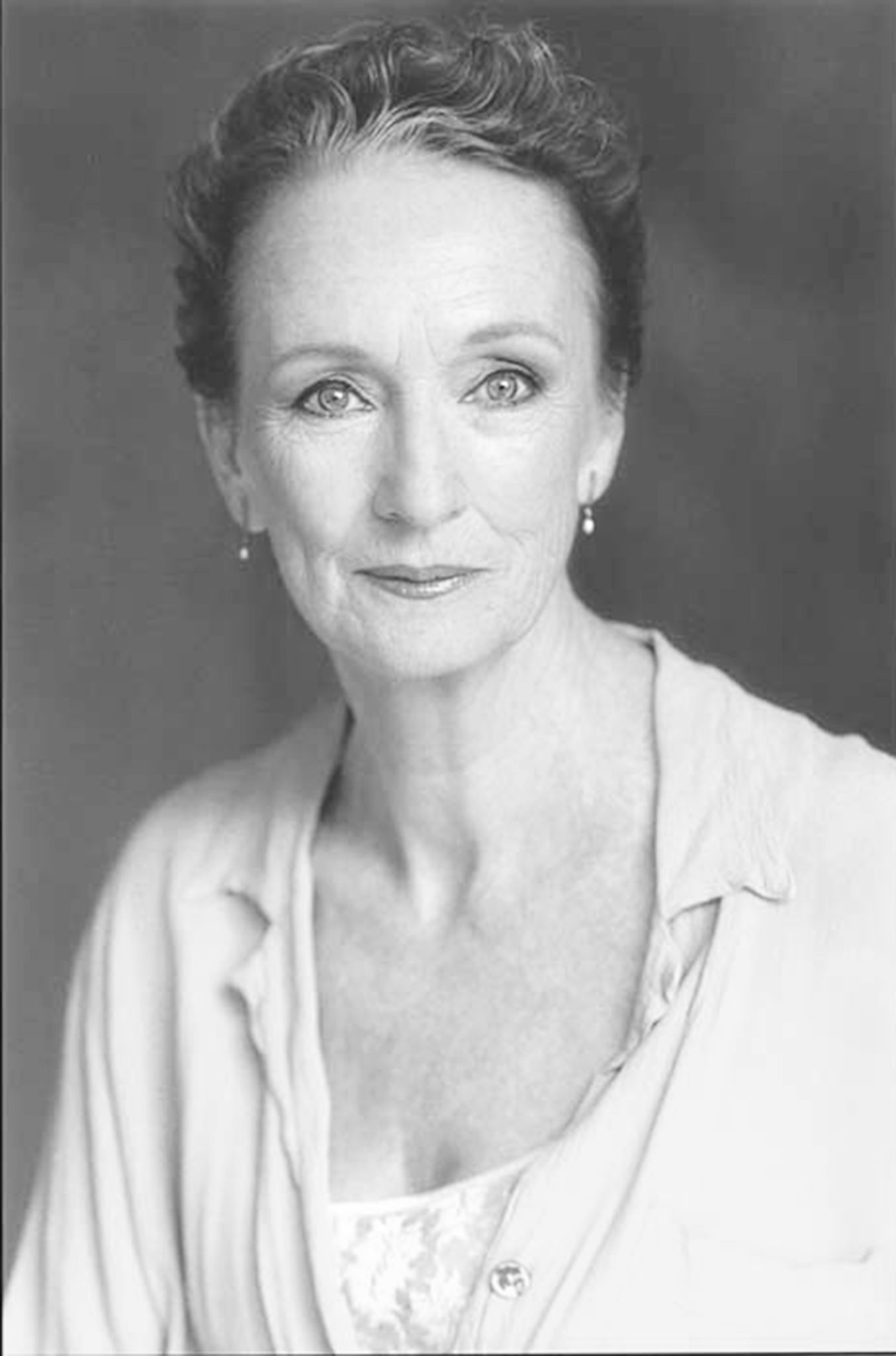

As I approached the Book Trader Cafe, I saw Kathleen Chalfant and gave a little wave. She waved back with a big smile and commented on our perfect timing. After insisting on buying my coffee, she sat with me at a table outside brushing the leftover rain off the seat. Today is not her first time in New Haven — she’s been in a number of shows at the Yale Repertory Theatre and the Long Wharf Theatre and has been in town for months rehearsing for the world premiere of “Mary Jane,” which opens at the Rep tonight.

For a famous Tony-nominated Broadway actress who is often recognized due to her role on Showtime’s “The Affair” and Netflix’s “House of Cards,” she is shockingly down to earth.

“So what do you want to know?” she asks, and when I respond with “everything,” she begins to tell the story of how she got here.

“I’m one of those people who never wanted to do anything else,” she tells me in response to the classic question: Why’d you decide to be an actor? As a child growing up in California, Chalfant’s grandmother used to take her to the movies. When she arrived back home, she would recreate the film as a one-woman show, acting out all the parts in her backyard. Like many artists, her parents did not consider acting a practical profession. If it weren’t for Chalfant’s older brother, she may not have approached theater as a viable career. Her brother was also in the performing arts, first as a stage manager and then as the manager of a ballet company, and he encouraged her love for performing — even though Chalfant isn’t a musical theater actor, Chalfant told me that she can sing the entirety of “My Fair Lady” thanks to her brother who gave her the score.

Chalfant always acted in plays in high school, but when she got to college at Stanford, theater fell to the wayside and she studied classical Greek. Though she says she chose the subject for silly reasons, she is still glad that she didn’t study theater. Noting that theater in college takes up a huge amount of time, she said that exploring other areas and learning more about the world are what truly feed an actor’s ability to mimic life.

After college she was supposed to go to grad school, but on a trip to Mexico with her future husband Henry, she realized it wasn’t what she wanted to do.

“I didn’t want to teach Greek to prep school boys,” she said.

“What do you want to do?” her husband asked her. When she responded that she’d always wanted to perform, he suggested she do just that.

“I’ve had such a fortunate time,” she told me, reminiscing on her career that “grew like topsy” in an incredibly disorganized but also exciting and successful way. After deciding to pursue acting, she spent time with her husband in Europe, and gave birth to their first child. She studied with acting master Alessandro Fersen in Rome, and found that acting in Italian was particularly useful to her education since “you’re already a different person in a different language.”

Soon after, she and her family returned to the States, now on the East Coast in Woodstock, New York, and her second child was born (in the midst of rehearsing for a run of “Major Barbara” in which she played the titular character).

She quickly found work in New York, taking classes with Wynn Handman, and through a series of off-off-Broadway jobs and connections, she continued performing.

“I kept reaching plateaus and thinking, this is how it’s going to be.” Then she ran into Tony Kushner.

She knew Kushner from her work at the New York Theatre Workshop, and when he saw her and her husband walking on the Upper West Side he told her that he had a part for her. For a few months, nothing came of it. In the meantime, Chalfant played Nancy Reagan as a nymphomaniac in a play called “Just Say No” and got to wear a “really cool red suit.” Then Kushner called her and asked her to come to a reading of what would become “Angels in America: Millennium Approaches.”

In the reading, she had the opening monologue, which was close to its finalized form, and played (among other characters) the rabbi. When she opened her mouth to speak, out came a very New York Jewish accent — she began reciting the monologue for me and I was reminded of family reunions on my mother’s side and my family’s imitations of old relatives who spoke more Yiddish than English. “And I didn’t know where that came from,” she mused, citing her Episcopalian European background, until she saw an old episode of Jack Barry’s game show and realized she’d modeled her voice off of the character of Mr. Kitzel. She tells me this with a laugh, and it seems incredibly relevant to her philosophy — she’d learned an authentic voice not from studying anything in particular, but from paying attention to everyday things seemingly unrelated to theater.

After six years of intense developmental work, which became a “day job” (a strange concept for a theater role), only five of the original actors were still part of the production, but the show was ready to premiere in New York City. Chalfant stayed on Broadway for a couple of years, and, when she left to again take other parts in smaller productions, she thought to herself, “Well, that’s it, that’s nice,” as if she had reached the peak of her career.

Chalfant’s lack of planning seems to have been a boon that allowed her career to develop in the varied and extraordinary way it did. Her ability to be open to unexpected opportunities led her to act in Henry V, her first Shakespeare performance ever, at New York’s Shakespeare in the Park. Through her willingness to forge connections and her constant interest in new work, she found a new play that Derek Anson Jones DRA ’85 (the assistant director for Henry V) asked her to read.

The play was “Wit,” a story about love and human connection told during the final hours of Vivian, a woman dying of ovarian cancer. Chalfant’s brother Alan, who had encouraged her love of the theater and helped her pursue acting, was visiting her the weekend she received the script. He had just been diagnosed with terminal cancer. She handed him the script and asked if it was true to his experience. It is, he told her, and if anyone asks you to do it, you do it.

The director offered her the role, and Chalfant starred as Vivian at the play’s East Coast premiere at our own Long Wharf Theatre. The play was a huge success, which she credits to the director, Jones (though she herself received stellar reviews and, as the lead, certainly contributed to the play’s extremely positive reception).

“What [Jones] knew that no one else knew at the time that he was HIV positive, and the cocktail that had been working stopped,” she tells me, and that his understanding of a terminal illness led to a fiery passion in his directing that led to the spectacular ending of the play in which Vivian is bathed, naked, in a fountain of light.

The show was quickly desired by the off-Broadway MCC Theater, but the artistic director of the Long Wharf, Doug Hughes, allowed it to move on one condition: that Chalfant come with it.

“It was a great gift to me,” Chalfant says, again humbling herself on her own contributions to the play’s success. Chalfant stayed in the cast of “Wit” for a few years, impacting many audience members who were survivors, patients, caregivers, and those left behind. Wit even made a travelling appearance to medical schools, in the hope that it would help doctors understand how best to comfort and care for terminally ill patients.

Chalfant has always pursued activism through her work and feels lucky that so many of the works she’s been a part of have been political pieces.

“I feel fortunate to have a way to speak — at least in a small way,” she says. Chalfant is passionate about theater’s ability to represent everyone, and emphasizes the importance of gender- and race-blind casting to make audiences question their expectations. Chalfant tells me about her experience from Sept. 11, 2001. She was living in New York, and there was a Muslim-run deli across the street from where she lived. “And for a couple weeks, people would drop in every hour to make sure everyone was okay,” she tells me. Perhaps in reference to the current political climate, she continues, “the first reaction wasn’t rage, it was what can we do?”

The show starring Chalfant that opens tonight aims to give voice to an underrepresented and underappreciated group, following the life of a woman taking care of a profoundly disabled child and the support network of women she finds. It’s a new play written by Amy Herzog, and from here Chalfant will go on to star in Sarah Ruhl’s newest work, “For Peter Pan on her 70th Birthday.”

“I’ve had great good fortune in the last year,” she tells me. In a career as enduring and varied as Chalfant’s, she has seen far bigger stages than her backyard in California but brings the same excitement for sharing stories she had as a little girl.

Contact Carrie Mannino at carrie.mannino@yale.edu .