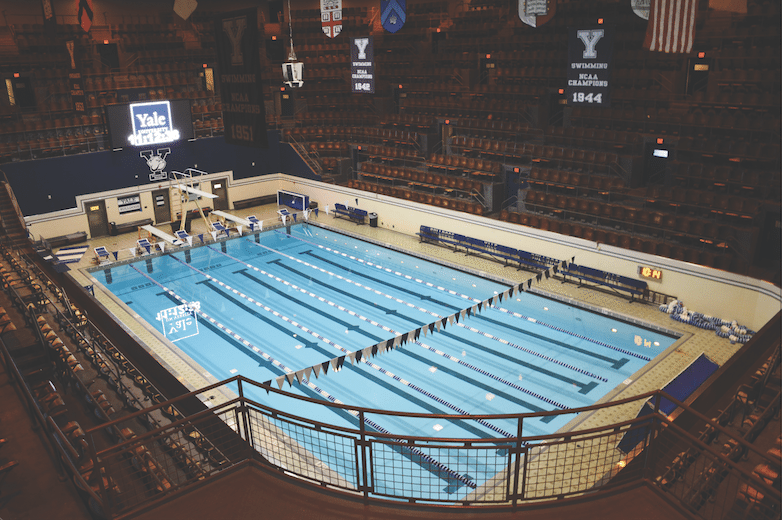

When the Robert Kiphuth Memorial Exhibition Pool opened in Yale’s Payne Whitney Gymnasium in 1932, it represented the pinnacle of modern swimming facilities. The gleaming 25-yard, six-lane pool sat at the base of a steeply banked funnel of 2,187 seats. Yale’s practice pool on the third floor, holding 330,000 gallons of water, was the largest suspended swimming pool in the world.

Together, these facilities were home to one of the greatest collegiate swimming programs in the nation. In addition to winning four NCAA titles between 1942 and 1953, the Yale swimming and diving team regularly sent alumni to international competitions, four of whom medaled at the 1964 Olympics in Tokyo.

But over the last 50 years, the program has seen periods of recession, and the once-modern pool is no longer a model facility.

In 2017, Kiphuth Pool represents a liability to the program, not an asset. The 85-year-old facility can no longer accommodate Yale’s swimming and diving program, as both NCAA and Ivy League meet standards require pools that are 50 meters long and at least eight lanes wide. These regulations leave Yale ineligible to host any competitions other than head-to-head meets.

Alumni who swam on Yale teams that regularly sent swimmers and divers to the Olympics view the aging pool as a symbol of neglect, and Yale coaches lament the facility’s inability to accommodate larger competitions.

“Our current facilities are amazing in that there’s so much history,” men’s and women’s swimming and diving head coach Jim Henry said in a December interview with the News. “I don’t think it’s a hindrance, and it has a certain charm. When it comes to hosting meets, the Ivy League championships in particular, we would love a facility that has the potential to do that. We can all agree it would be great to have a championship-specification site off campus.”

Members of the Yale swimming and diving alumni community agree with Henry. For the last two decades, they have been advocating for a modern facility that will allow the program to remain competitive.

In 1997, alumni donated $2.22 million to kick off fundraising efforts for a new pool. But this initiative quickly fizzled, and the subsequent fits and starts — coupled with the University’s past investment decisions — have left some alumni wondering when Yale swimming and diving will receive its new pool.

SEEKING A SOLUTION

Kiphuth’s age is only one of its problems.

In addition to the issues arising from its size, the pool does not have water-filtering gutters — a feature of most modern pools — so swimmers have to strain against waves of water pushed at them by Kiphuth’s flat back walls. And the lack of a separate diving well limits training space, forcing the diving team to practice from 2 to 4 p.m. on weekdays, a time that often conflicts with classes.

Still, this does not seem to have limited the swimming and diving programs, both of which have made steady improvements in recent years. Under Henry, the women’s team won the Ivy League championship this year, its first since 1997. The men, meanwhile, who are now also coached by Henry after the April 18 resignation of former men’s head coach Tim Wise, have finished in the top half of the league for seven consecutive seasons.

In an effort to bring Yale’s swimming and diving program up to speed, for over 20 years the team’s alumni have combined their resources to raise money for a new pool and sought to work with the University to find a lead donor.

In 1997, former Yale swimmer Walker Buckner ’65 was approached by his former coach, Phil Moriarty, who asked if Buckner would consider donating toward the construction of a new pool. Everett MacLeman ’42, another Yale swimming alumnus, had provided detailed engineering plans for a potential renovation.

Moriarty had joined the Yale staff as a diving coach in 1939 before succeeding Robert Kiphuth, the pool’s namesake, as head coach in 1959. Upon assuming the head coaching role, Moriarty coached seven Yale swimmers and divers to Olympic gold medals and led Yale to separate winning streaks of 42 and 76 consecutive dual meets before retiring in 1976.

When approached by Moriarty, Buckner did not hesitate. He signed a check for $100,000, earmarking it for the renovation fund with the hopes of reestablishing Yale’s status as an elite swimming program.

“They talk about these Olympic stars from the 1960s. It’s just ridiculous. They let the program languish and they never built the pool,” Buckner said. “The team had six people go to the Olympics in 1964. It was a great, great team. [The University] basically abandoned the swimming program.”

Moriarty’s fundraising efforts solicited somewhere between $5 and $6 million in donation pledges, $2.22 million of which was actually donated. After receiving the donations, the University placed this money in a type of low-growth fund typically used to hold money for capital projects. Sixteen years later, the $2.22 million was transferred into a fund linked to the endowment.

Though the University requested $10 million to $20 million for the pool, fundraising efforts stalled for the next decade and a half.

Some donors feel the money should have been invested in the endowment before 2013: Several alumni donors claim the decision could have cost Yale more than $18 million in potential growth from the alumni donations, although Yale Director of Athletics Tom Beckett said the athletic department could not speculate on the potential growth of the fund.

A March 2014 meeting between three members of the Yale Swimming and Diving Association Steering Committee and University President Peter Salovey increased collaboration between alumni and the administration and promoted consideration of a range of replacement proposals.

Fundraising efforts were renewed in April 2014, and by October 2015, $9.1 million had been donated for the renovation. But no money has been raised for the pool since then, and for now, the project remains in search of a lead donor.

MOVEMENT IN THE 90s

Early in Beckett’s tenure, former University President Richard Levin asked the Athletic Department for a list of potential capital projects, and the pool construction was added to the list. As soon as the pool project was approved by the University, all donations were placed in a low-interest “active plant fund account” — as is standard protocol for capital projects — rather than invested in endowment.

During the most recent Yale Bowl renovation, for example, the University placed donations in a plant fund account for over a decade until all necessary funding for the project was obtained. The Bowl’s $30 million renovation was completed in 2009.

However, while other capital projects like the Bowl renovation received a large donation early in the process, the University struggled to find a lead donor to energize fundraising efforts for the pool, and the money sat in the active plant fund account for the next 16 years.

“Capital gifts are put into plant funds because it is assumed they will be used in a timely manner,” Beckett said. “The pool was an anomaly in that we did not have a leadership donor in 1997 or 2014, but the University kept the project approved in the hopes that one would come forward.”

After the 2008 financial crisis reduced the University’s fundraising and endowment yield, the department needed to find new sources of funding for athletic programs. According to an email sent on Dec. 18, 2014 from Beckett to Buckner, the Athletic Department, along with the provost and vice president of finance, decided in 2013 to create a University Fund Functioning as Endowment with the funding obtained for the pool project.

The UFFE would use the spendable yield from the endowment, about 5 percent of the market value, to defray the swimming and diving program’s operating expenses. This would allow the Athletic Department to avoid budget cuts to the swimming program, Beckett wrote.

The decision was made without approval from donors, Beckett said.

“We made this request because we had two choices: to find new sources of revenue to support our programs, or to cut our budgets and be unable to provide a great experience for our student-athletes,” Beckett wrote in the email to Buckner. “The decision to create this endowment was made during a budget cycle with significant financial pressure on the University and the officers of the University approved the decision.”

Yale Athletics planned to move the original donations, along with the growth in the UFFE fund, back into an active plant fund account once construction began on the pool. Between 2014 and 2017, the growth of the UFFE fund provided $578,706 to Yale swimming and diving, and the original donations of $2.22 million grew to $3.43 million, according to Beckett.

Upon contacting members of the Yale administration in 2015, Buckner said he was shocked to find that the value of his donation had not appreciated at all. Even though fundraising for the pool had been put on hold, his donation had never been invested in the endowment. Eighteen years later, Buckner’s $100,000 was still worth $100,000, and the $2.22 million was still worth about $2.22 million.

“I assumed [Yale] would have invested it,” Buckner said. “The only reason I got back on it was because they wanted more money from me. I haven’t given them a nickel [since] because it was so ridiculous.”

Based on calculations using endowment return data obtained from the Yale Investments Office website, alumni donors calculated the expected value of the $2.22 million donated in 1997 if the University had invested the funding in the endowment at the time. According to their calculations, by 2014, the $2.22 million would have appreciated to over $20 million — enough to fund the construction of a separate swimming and diving facility near the Yale Bowl without any additional donations. However, it is unclear if this estimate is accurate.

Beckett said the Athletic Department could not speculate on the theoretical growth of the donations.

Though the University followed standard protocol for capital projects in holding the initial pool funding in an active plant fund account, the management of the 1997 donations fomented frustration among alumni who have been working on the project and feel the money should have been invested in the endowment before 2014.

“The argument for the low-interest account was that [the University] wants to keep the money liquid and available to commence with construction,” YSDA Steering Committee member Steve Clark ’65 said. “But there’s never been enough money to build the pool. Somebody at some point should have said we don’t need to keep the money liquid.”

SEARCHING FOR THE BIG GIFT

With minimal growth in the $2.22 million donated in 1997, the Yale Swimming and Diving Association remained far short of the money it needed to commence construction. Alumni mobilized to resume fundraising for a new pool.

The first concerted effort since 1997 to get the pool project off the ground occurred in 2010, when a group of 150 Yale swimming and diving alumni convened to discuss how to lobby the University to overhaul Yale’s swimming facilities. A five-member Steering Committee was formed to lead fundraising initiatives and communicate with the University. After seeking donation pledges and researching renovation options for two years, the committee entered discussions with Yale Facilities in January 2013.

The renovation of Kiphuth Pool to create a 50-meter, nine-lane, 9-foot-deep pool with a separate diving well would require the back wall of the existing facility to be pushed out towards Lake Place. The structural changes would cost an estimated $47 million, far beyond the fundraising capabilities of the alumni. But the committee presented a proposal for the construction of a cheaper swimming and diving facility near the Yale Bowl, which would cost around $20 million — a total nearly covered by alumni donation pledges.

“The Steering Committee reluctantly came to the conclusion that the Payne Whitney solution would make the pool the most expensive ever built in the United States,” Clark said in a December interview. “We didn’t think it was realistic. We didn’t think anyone would consider donating to a $47 million gold-plated pool.”

However, according to a February 2014 article in the News, the alumni were met with resistance from the Yale administration, which rejected any proposal that would remove the swimming and diving facilities from Payne Whitney, but did not offer to contribute any funding towards the project. In an email to the News at the time, University Vice President for Development Joan O’Neill said that all athletic facility projects had to be funded by donations, rather than through University contributions.

After continued lobbying, the YSDA secured a meeting between three members of the alumni Steering Committee and Salovey. On March 28, 2014, the Committee presented three proposals to renovate Kiphuth Pool. One was a new eight-lane pool and diving well within the existing Exhibition Pool space, while the other two were 50-meter pools that necessitated an extension of Payne Whitney’s current back wall toward Lake Place. The cheaper option — building a pool near the Yale Bowl — was not considered at the time.

By mid-October of the following year, the project had received $9.1 million in donations and alumni had formed a new six-person committee, Fast Water in Our Future, to work closely with the administration on fundraising efforts, according to a November 2015 article in the News. The University expanded its donor search to alumni outside of the swimming and diving community.

But with the administration still favoring the $47 million renovation proposal, the project required a lead gift of $25 million or more to anchor fundraising efforts.

Since the February 2014 meeting between Salovey and members of the Steering Committee, increased communication between the University and the YSDA has invigorated a renewed search for this lead donor.

“We have set up regular meetings on the Fast Water in Our Future committee with Yale Athletics and Yale development,” YSDA Board President Matthew Meade ’87 said. “We have really clear channels of communication. … We probably talk every four to six weeks.”

Members of both YSDA and the University Office of Development have searched for donors outside of the swimming and diving alumni community, spurred on by lead gifts for recently built pools at Princeton and the University of Texas coming from donors unaffiliated with swimming and diving.

“Our department and the University development staff have been working with the alumni and friends of Yale Swimming in a most cooperative way to fund the project to create a new pool complex for our community,” Beckett said. “This is an ‘all hands on deck’ effort.”

Last fall, the YSDA produced a brochure advocating for the construction of a new pool as “An Investment in Community” to appeal to potential donors not affiliated with the swimming and diving programs.

The brochure touts the potential benefits of a new aquatic facility to users across Yale and New Haven — expanded recreational and instructional swimming programs, community outreach initiatives — along with “an optimal ‘fast water’ competition pool” to benefit Yale’s swimming and diving teams. It invites donors to give in one of three donation brackets: $50,000 or more, $1 million or more and $25 million or more.

At a recent YSDA board member meeting, members of Fast Water in Our Future asked each board member to send the pamphlet to one friend outside of the swimming and diving alumni community. YSDA members are hoping to seize upon the women’s swimming and diving team’s 2017 Ivy League title to inject new momentum into the fundraising process, Meade said.

“We feel like we’ve tapped a lot of the swimmers, and we’re going to friends of swimmers,” YSDA board member Melanie Ginter ’78 GRD ’81 said. “I think the University is doing a very good job of talking to potential donors each time they go out. It’s a long process and we’re hopeful.”

According to Meade, the YSDA and the University still have not decided between the construction of a separate facility and a more expensive renovation of the existing pool, though the $25 million lead gift sought on last fall’s brochure is more money than is needed to build a facility by the Yale Bowl.

“Securing a lead donor is critical to the overall success, and once secured, it is likely that multiple gifts will be forthcoming,” O’Neill said. “We continue to all be focused on securing a lead gift or gifts.”