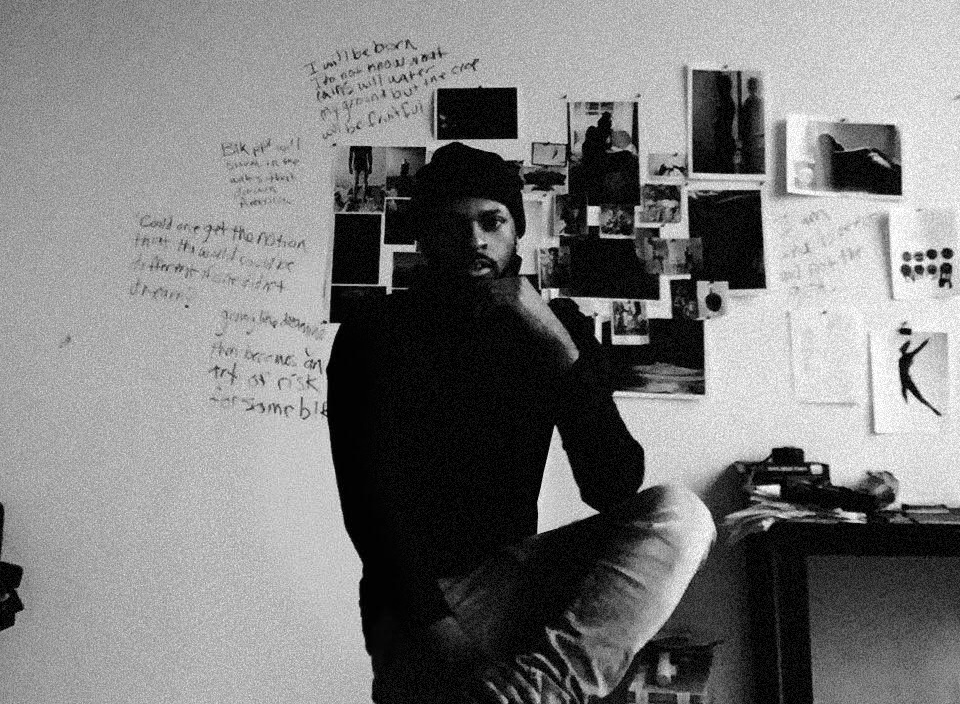

Shikeith Cathey

Interspersed throughout the collage of photographs that covers Shikeith Cathey’s ART ‘18 studio wall are handwritten messages, scrawled out in a hurried hand. Some are messages of inspiration: “Look up black boy” and “Dream,” while others take a more defiant tone: “Blk ppl will swim in the waters that drown America.”

Cathey, a first-year MFA sculpture student, told me that the messages are “short poems” that come to him as he works in his studio. Poetic is a good way of thinking of Cathey’s work, as his photographs, films and sculptures explore moments of tenderness and vulnerability in the lives of black men. Best known for his 2014 documentary film #blackmendream — which, through a series of interviews, examines the emotional experiences of black men — Cathey has been covered in NPR and the Atlantic and is recipient of multiple artist residencies and grants. Last week, after a screening of #blackmendream at Yale’s Afro-American Cultural Center, I sat down with Cathey to discuss his artistic practice, representations of black men in art and his life before Yale.

Q: Tell me about how you started out in art.

A: I went to Penn State, finished up there and had my eyes set on a career in editorial fashion. Throughout my time at Penn State, I had several internships, working with fashion photographers and production companies like IMG World and Teen Vogue. That was the goal: to become a fashion photographer or to work with fashion magazines, because, at that point, I was literally terrified of creating anything that was autobiographical. So, you know, I just kept with the fashion photography, creating beautiful things that didn’t have any type of connection with me. After school, I went to New York and worked at StyleWatch magazine for a bit. Eventually, I left New York and went back home to Philly, and then, it just clicked. [I said], “You know what, hop back into your practice!”

So around 2012 I started to do little things. I started with a video, called “Stigma.” I invited a dancer from Philadanco! in Philly to come into this studio space that I had the opportunity to use, and I created this video where he is dancing with himself. I had choreographed it so that it could talk about a lot of the things I talk about in my work today, but just not having that language at the time, but just kind of visually seeing it. You can go towards double consciousness, metamorphosis, regeneration. That was the first thing.

Q: What was the “click”? What was the moment?

A: I think you just have it inside — it’s just this moment, where it “clicked.” It’s weird. But it hadn’t clicked fully because I was still doing this and starting to photograph black men. Prior to “Stigma,” all throughout my undergraduate education, I didn’t photograph men. I was photographing women the entire time.

The idea was to use these men as surrogates for whatever at that point I was trying to lay out. I continued on making photographs, and eventually around 2014, about two years later, I received a message from one of my close friends who had started an independent experimental gallery and residency program in Pittsburg. She was pitching a grant. And at that point I was like, “you can be an artist and like receive funds and things like that?” I didn’t know anything about that. And so she proposed this grant in Pittsburgh, it was called the Advancing Black Arts grant through the Heinez Endowments at the Pittsburgh Foundation. And at that point, I developed a lot. I was doing a lot of online researching and educating to build up a language around my work and my practice outside of fashion. And I proposed #blackmendream.

But prior to going to Pittsburgh, I decided to start getting more transparent with the work, to visualize some more personal history. It started with the balloon. When I was younger, I dealt with a lot of ostracizing from other black boys and black men who I grew up around. Whether it was in a school setting, where I was teased, mocked and bullied for being who I was. Or, back home, where I experienced sexual assault. I harbored a lot of those feelings, and internalized them—it led to a long battle with depression as a child, and eventually I attempted suicide. For a very long time, I had this internal conflict in relation to creating artwork that was transparent. And a lot of that has to do, you know, I was making “Art,” but I literally stopped making art in middle school when I connected — to protect myself, my conscious — connected making art with homosexuality, queerness, or being strange, or being feminine. All of these things that I embodied, but was afraid of at that time, because of being around men and boys who were built up off that false bravado in order to protect themselves from each other or whatever greater, systemic forces. That hardening left little Shikeith in the dust, and I stopped making art.

I went through college and literally did fashion because it was the next best thing [to making my own art]. But what would happen was, I would have dreams from that time, all the way through college, after college, and they would be repetitive. I would be on a roof and all those boys and men who had in some way, or another, impacted me or traumatized me or ostracized me would be on this roof chasing me. And at the edge of the roof I would see a balloon, and I would go to reach for the it and I would fall to my death or just wake up. But I would have that dream for a really, really long time.

So, one day, following leaving New York and being back in Philly and starting to hop back in my practice, I said, “What the fuck is this balloon? Why do I keep having these dreams about this balloon?” And so I visualized it, and I created this photograph “Dreams in Black and White I.” And that was when the balloon became that signifier and symbol in my work across photograph, film, and now sculpture. And I’m still trying to figure out what exactly it means. But I would have that dream, and the last time that I had that dream, I grabbed the balloon and floated away.

Q: Tell me about your trajectory from photography and film to sculpture and glass.

A: It happened in Pittsburgh when I had my first residency, around 2014. Well, to start from the beginning: I started photography in the 11th grade, so I’ve been shooting for almost 12 years now. I’m committed to images. But sculpture came about in 2014 where I wanted to start doing more installation-based works. But I didn’t study sculpture as an undergraduate, so one of my close friends was helping me work through a lot of my ideas. But I always knew it was going to be figurative work. So the transitions from photographs and film to sculpting with clay or doing life-casting was really easy, to be honest, because I became so familiar with the body just through those first two mediums. Even with fashion, I was just aware of the way light hit the body, and that helped me when I first moved into ceramics and sculpting the figure, and just thinking about light. Now, it’s just figuring out which materials relate to or feel autobiographical and visceral. The challenge for me, with sculpture, was to have that visceral connection with it. When I first got the opportunity to work with glass I was like, “Oh my god, this material feels autobiographical.” It’s sharp, it will cut you, but it’s also really fragile. It’s also translucent — and that just felt like me. And the process of creating it — the fire, the warmth — the whole process felt good for me.

Q: So you mentioned that you underwent a process of self-education. How did that begin, and what did it look like?

A: It initiated from the internet, and from social media. Tumblr was such a great source for informing myself about art history, different artists, different essays and articles. Then of course the network of friends you meet from across social media who have interesting art. All of that was crucial to me becoming more knowledgeable about the path I was heading on, within the arts, and the lineage of people who came before me. So, you know, I’m browsing on Tumblr, and I come across Marlon Riggs or Isaac Julien, and I’m like, “Who the hell are these people? How did I not know they existed?” I remember being back in undergrad and being in art history, and kind of tapping out along the way, because I’m like, none of these people are interesting. I think that also contributed to the reason why I felt like I couldn’t be an artist, because the art history courses were heavily dominated by white male artists. But still, at that time, I was afraid to approach anything personal that I knew would be the story of my work that I had to explore. But yes, the internet: that was my library, that was my post-undergraduate education. I have a shit ton of text message conversation between me and friends, and we are just talking about things — through things — and eventually I ended up here at Yale. But the internet, social media and building networks across those platforms was crucial to my growth. And I still use that in my work, especially in #blackmendream, which started from a Facebook post.

Q: I want to ask about the sentence you have here on the wall: “subvert the exploited black male nude, show the psychological effects and ruptures in self-desirability.” I’m interested in the fact that so many of your images, photographs, are of nude men. How, in your practice, do you think about exploitation while making these images? And there’s also an erotic element —

A: Sense of self, sensual, tender —

Q: And I’m also thinking of the photographs of the man lying on his back, or the men standing behind each other. You’re taking bodies that have so much historical and cultural weight, and that’s a burden you have to deal with as an artist. How do you deal with that?

A: I had a studio with Fred Moten, and we were talking about that burden. And this work is for me, it feels like it’s lifting that burden. You see these bodies, in their natural state, nude, in solitude, lifting one another up, or literally flying. I think for me, the nudity is more about connecting those bodies to the full spectrum of humanity, and giving them access to that. Whether it be more erotic, or sensual, or sexual, or just quiet. I think these bodies deserve the full experience, the full spectrum of what’s rightfully theirs to have, as far as being. With no apprehension, but just being. That’s really important to me. And then also I do know that I could—they could be clothed—but I think for me, the nudity just, it just feels like it’s going up against what’s already been perceived as the nude black male body. And kind of just fucking with that. But also handling these bodies with a care, a tenderness, because I am the artist.

Q: These could be seen as tender, or sexual moments, but not in a pornographic, objectifying way. If anything, they are very loving moments —

A: That’s what they were created from: love. My love for black men, and wanting that reconciliation to happen, and wanting us to see one another, touch one another and lift one another up.

Q: My last question is about emotion. It seems like your work, from #blackmendream as well your photographs, is doing a lot with affect and emotion. Could you speak about that, more broadly, about what it means to integrate vulnerable emotions into your art?

A: I know, from experience, with other black men and boys, that there is a hardening that happens very early on when you’re taught not to be yourself. And a part of that teaching, or that condition, is a draining of any type of human behavior — you kind of become restricted to a very specific type of emotionality, which is very hard, which is literally emotionless. So me, coming out of photographs, and knowing the history of photography and the power of images in contributing to shifting the cultural imagination, and seeing something new, seeing something that’s possible. I just, literally started to photograph people, black men, being emotional. Crying. Embracing one another. And that just came out of an urgency just to see it, to see what it looks like. It came from a wonder of, “how does that look?” I hadn’t seen it. I hadn’t seen it on TV, magazines, movies, museums. So I went and created it.

This interview was edited for clarity and flow.

Contact Joshua Tranen at joshua.tranen@yale.edu .