Xian Gu SPH ’18 assumed praying mantis position on the ice as she pushed out of the starting blocks and slid, delivering a polished stone across the ice. Two team members swept the stone along until it landed near the center of the target.

With two special curling soles on my feet, I stood beside her on the ice in awe. “It’s just like running,” she turned around and smiled at me. But when I tried, I almost tumbled to the ground. Curling is harder than it looks.

With two weeks to go until Collegiate Curling Nationals, the country’s premier collegiate curling tournament, the Yale team was focused. Last year — the third year of the team’s existence — was the first time they qualified, and they were happy just to get there. But this year was different. Nearly all of the team’s members were back and a year more skilled. They now had a chance to compete with the cream of the crop — the true curling juggernauts.

Curling is an easy target for ridicule. It’s slow-paced, strategic and Canadian. But these are the same reasons I was attracted to it in the first place. I’m a big fan of Vermont, arguably the most Canadian state in the union. I like maple syrup and cold temperatures. When the Yale Daily News asked if someone could write a quick story about the curling team for the sports section, I was happy to volunteer. I would go on to interview the president, get some silly quotes about a silly game and come out with a fun, whimsical story. The team, which had been asking for publicity, was happy. The editors were happy that someone took the story. Of course, I was happy too: I told my friends I was writing about curling!

But the “spirit of curling” — the aura around the sport — has a way of drawing people in. What started as a short interview soon inspired me to watch televised curling coverage, pack into a ZipCar with the team, observe them as they prepared for nationals, drive up at 5 a.m. for the National Collegiate Curling Tournament in Utica, New York, and dedicate this feature to the sport and its devoted athletes.

—

Most people don’t know Yale has a curling team. The Yale Graduate Curling Club, started in 2013, only has three undergraduate members: Elizabeth Coquillette ’18, Joseph Vinson ’18 and Nick Nordlund ’17. But that’s not to say they are not looking for undergraduates. They are. They really want some undergraduates. But, as of now, the club doesn’t have enough underclassmen to get a table in the extracurricular bazaar, so it’s hard to get the word out.

Part of the problem might be that almost no one — besides perhaps Yale’s vibrant Canadian community — really knows much about curling at all. Even in the Winter Olympics, filled with strange sports like bobsled, short track speed skating and biathlon — an event combining cross-country skiing and rifle shooting — curling receives the brunt of the mockery. David Letterman said curling was “a lot like hockey, minus the speed and excitement.” Stephen Colbert called it “America’s fastest growing sport that involves sliding rocks on frozen ice.”

The goal of curling, like most sports, is to score more points than the opposing team. Players must slide a 40-pound polished granite stone across a sheet of ice and land it closer to the center of a target than the opponent. At all times, there is one thrower, two sweepers and a captain called the skip. The skip tells the thrower and the sweeper where they want the shot. The thrower then pushes off the starting blocks in a crouching position, left foot in front of right, and sends a stone sliding down the ice. Then the yelling ensues. If the shot is not going fast enough or not curling enough, the skip yells out commands and the sweepers ferociously sweep in front of the stone, guiding it to where they want it to go.

There are three different types of throws: guards, takeouts and draws. If players want to make it harder for their opponents to land in the house, the target, they will throw a guard. If players want to knock their opponents’ stones out of the house, they will throw a takeout. And finally, if they just want to land right on the button — the center of the house — they will throw a draw, a normal shot. In every round, each team throws eight stones. At the end, whoever has a stone closest to the center gets a point. If one team has more than one stone closer than its opponents’ best throw, it gets more points. After eight to 10 rounds — depending on the competition — a winner is declared.

Curlers are always prepared to pitch their beloved sport — it’s one of the few sports you actually have to pitch. If you ask baseball players why they like baseball, they’ll probably give you a confused look and maybe tell you that they like pitching or hitting. But in curling, you have to start from square one because the person you’re talking to probably has no idea what curling is. For this reason, curlers have a few answers prepared. These three things — what I like to call the three tenets of curling — will inevitably come up: the spirit of curling, broomstacking and the comparison of curling to chess.

At six feet tall with wispy blonde hair and black-rimmed glasses, Fabian Schrey GRD ’19 is the embodiment of the spirit of curling. Though his curling career only started last year, he is already the Yale club’s president. His love of the sport is palpable and contagious. After he answered a question, he would look at my notes and answer another one before I had time to ask it myself. Schrey is on the club’s competitive team — the one that competes at tournaments across the Northeast and occasionally in Minnesota. But for him, curling is more of a community than anything else. No member of the club — even the ones on the competitive team — curled before they arrived at Yale.

The Spirit of Curling is what makes curling, curling. It is the respect curlers show not only to their competition, but to the sport itself. In the Bridgeport Curling Club, the team’s practice facility located half an hour from downtown New Haven, the 19 specific rules all curlers are expected to follow are laminated and displayed throughout. “Etiquette is the courtesy and sportsmanship that you show your teammates and your opponents so that everyone can enjoy the game and play as well as possible without being distracted,” the sign read. In addition to arriving on time you must also “shake hands with your opponent, tell them your name and wish them good curling.” After the game, the members of the winning team buy their opponents a drink. The losers, after clearing off the ice, should offer to reciprocate. This is broomstacking. Unlike in baseball, where slight breaches in etiquette can incite a brawl, incidental mistakes are handled in a cordial manner. “If etiquette or custom is temporarily forgotten, experienced curlers should provide a friendly reminder of the oversight.” And for God’s sake, after the game, be a good sport. “Do not critique the skills of new members publicly, nor complain about your team’s misfortune.” All players are expected to act like Canadians.

Since there are only 30 collegiate curling teams in the country and lots of downtime between games during tournaments, teams get to know each other pretty well through broomstacking. Yale’s team is quite close to the curlers of the University of Pennsylvania. While there is a lot of drinking involved in curling (some teams take a ceremonial shot of whiskey before playing in a championship game), broomstacking is about fostering community. There’s also a lot of card-playing. Uno is a popular choice.

Patrick Huang pointing out where a shot should go. Courtesy of Joseph Cosentino.

But perhaps the strangest of the three tenets of curling is the insistence on comparing curling to chess. The most notable similarity between the two is that both require strategy. Although some Yale team members lift a few times a week as part of training — including Michael Parker GRD ’18, the competitive team’s captain — curling is not a game of strength; it is a game of planning and execution. The best curlers go beyond planning a few throws or even rounds ahead and think about what the opposing team might do. Players told me that Patrick Huang MED ’19, one of the team’s most dedicated members, can remember specific shot details from every match he’s ever played. But chess doesn’t require any sort of physical execution beyond picking up a piece and putting it somewhere else. In televised curling, teams often discuss their strategy directly in front of their opponents. When the strategy is that obvious, the team just has to make a nice throw. The same would not happen in chess. I think curling is more similar to a combination of shuffleboard, bocce and darts. But the chess comparison doesn’t go away so easily: “Many good curlers are good chess players,” Schrey told me. Maybe I’m missing something.

—

On a Sunday afternoon, I packed into a Ford Fusion Zipcar with four other members of the curling team and headed towards the Bridgeport Curling Club for the weekly practice.

“Cramming into a car and getting stuck in traffic is an integral part of the curling experience,” said Chelsea Blink GRD ’21 who was sitting in the passenger seat. Parker, the most skilled member of the team, was to my left. His orange-tinted sunglasses sat directly under his floppy brown hair. He wore blue and white checkered pants. Curlers are well-known for having great pants.

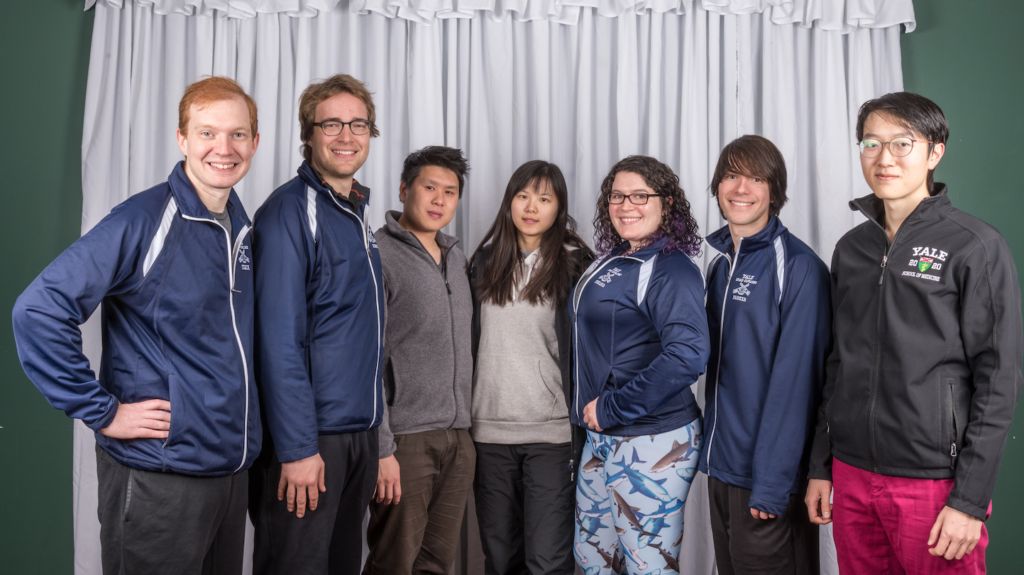

All the members of the team (L to R): Ed Scimia, Fabian Schrey, Patrick Huang, Xiang Li, Chelsea Blink, Michael Parker, Dennis Wang. Courtesy of Joseph Cosentino.

The Bridgeport Curling Club’s lounge is cozy and carpeted. It has a few circular wooden tables, some well-worn couches, and a TV that is hooked up semi-legally to Canadian cable. TSN, Canada’s national sports channel, airs a lot more curling and hockey than its American counterparts. Like every other curling club, the club has its own bar.

Before practice started, Parker and Schrey prepared the ice. Parker, wearing something that looked a bit like a leaf blower, began covering the ice with little frozen droplets. Schrey “nipped” the ice — evening out the raised droplet surface. This preparation removes some of the ice’s surface area, allowing stones to slide across the ice with less resistance.

When Parker and Schrey finished, the team and I moved out of the nice warm lounge and onto the ice. Though the room is kept at 38 degrees, Dennis Wang ’14 SPH ’16 MED ’20, one of the members of the team heading up for nationals, wore only a black V-neck T-shirt and jeans. “You get warm,” he said. “I bet I’m warmer than you are.” He was right. I was shivering even in my boots and winter coat.

On the sheet next to us, Ed Scimia, the team’s volunteer coach, led a match between the Yale competitive team and a few members of the Bridgeport Curling Club. Though it was a low-stakes game, both teams wanted to win. Schrey, sweeping with vigor to help change the trajectory of a shot, began shouting the word “schiezer.” There’s no swearing in curling, but there is no rule against swearing in other languages. Schrey, an international student from Germany, can get away with it.

At the end of the game, the teams shook hands and thanked each other for the game. After stacking their brooms, they met in the lounge to drink and eat some slices of cheese and pepperoni on crackers. There was one more practice planned, and then right as spring break started, the competitive team would head to nationals. They were ready.

—

The Utica Curling Club, located in the middle of nowhere, New York, is the largest curling facility in the Eastern United States, and one of the oldest in the country. A member of the Grand National Curling Club — a union of American curling clubs — the Utica Curling Club hosts some of the most important curling tournaments in the country, including the Collegiate Curling National Championships.

The tournament started with a procession throughout the club. The 16 participating teams and their coaches walked in a single-file line through the facility, rhythmically hitting their brooms against the ground, as they followed a bagpiper wearing a kilt, the leader of the whole procession. With all the teams lined up on the ice, the spokesperson for the tournament began to speak. But he messed up the order; it was actually time for the national anthem. He was interrupted by an amateur trumpet player and Utica Curling Club member who got better as he went along. After some quick announcements, the athletes, led by the bagpiper, marched off the ice. The players wished each other “Good curling,” and the tournament officially began.

Yale’s team—composed of Parker, Schrey, Huang, Wang and Blink — started off strong.

In the team’s first game against the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a few mistakes made by the Yale team near the end didn’t leave the MIT players enough time to challenge Yale’s robust lead. The next game — against the University of Wisconsin, Green Bay — went even better. “We were never in a position where we felt like we would lose the game,” Schrey said. “Every end after another, we had it together.” Wang and Schrey were in such good moods that they began humming and singing (respectfully) on the ice.

The University of Oklahoma, the final team in Pool B — the group Yale was in — was a good opponent. However, Parker had a fantastic match, leaving Yale undefeated through pool play. The Yale team had earned its spot in the A semifinal. The Yale team faced its toughest opponent yet: The University of Minnesota, the winner of pool C. Just a few years ago, Minnesota had won a national title. On their way to the semi-final, they had already defeated Penn, last year’s champion.

The game was tough. “If we didn’t take a shot that was absolutely perfect, they didn’t give us a chance to make up for it,” Schrey said. “We didn’t play badly. It’s just Minnesota played extremely well. In the end, the team lost 9 – 1, eliminating them from the tournament. Even though Minnesota went on to win the championship over Nebraska, Yale did not get a chance to compete for third, fourth or even fifth place. The way the tournament was set up, even teams that lost games earlier in the tournament were given a chance to compete for medals. “Is [the system] perfect?” the tournament brochure says. “No it’s never perfect.” Yale was just unlucky.

Patrick Huang and Dennis Wang sweeping. Courtesy of Joseph Cosentino.

But curling, even at its most competitive, is not all about winning. A true curler would rather lose than win unfairly. When members of the team talk about what they love about curling, it’s almost never about what happens on the ice. They talk about listening to hours of Fall Out Boy and Taking Back Sunday to annoy Schrey on the way to a tournament. They talk about Schrey’s revenge — when he curated an album of Swiss-German marching band music and forced everyone to listen to it. They talk about playing cards until 1 a.m. with the curlers from Penn. And they talk about walking across a frozen pond in the middle of winter on the way home from a curling tournament in Rochester. John Shuster, a bronze medalist on Team USA, put it best: “curling has a way of attracting some of the best human beings.”

Maybe curling is ridiculous. But if sweeping as hard as you can to affect the trajectory of a 40-pound granite stone is weird, I don’t want to be normal. I could use a little more ridiculous in my life. I could use the Spirit of Curling.