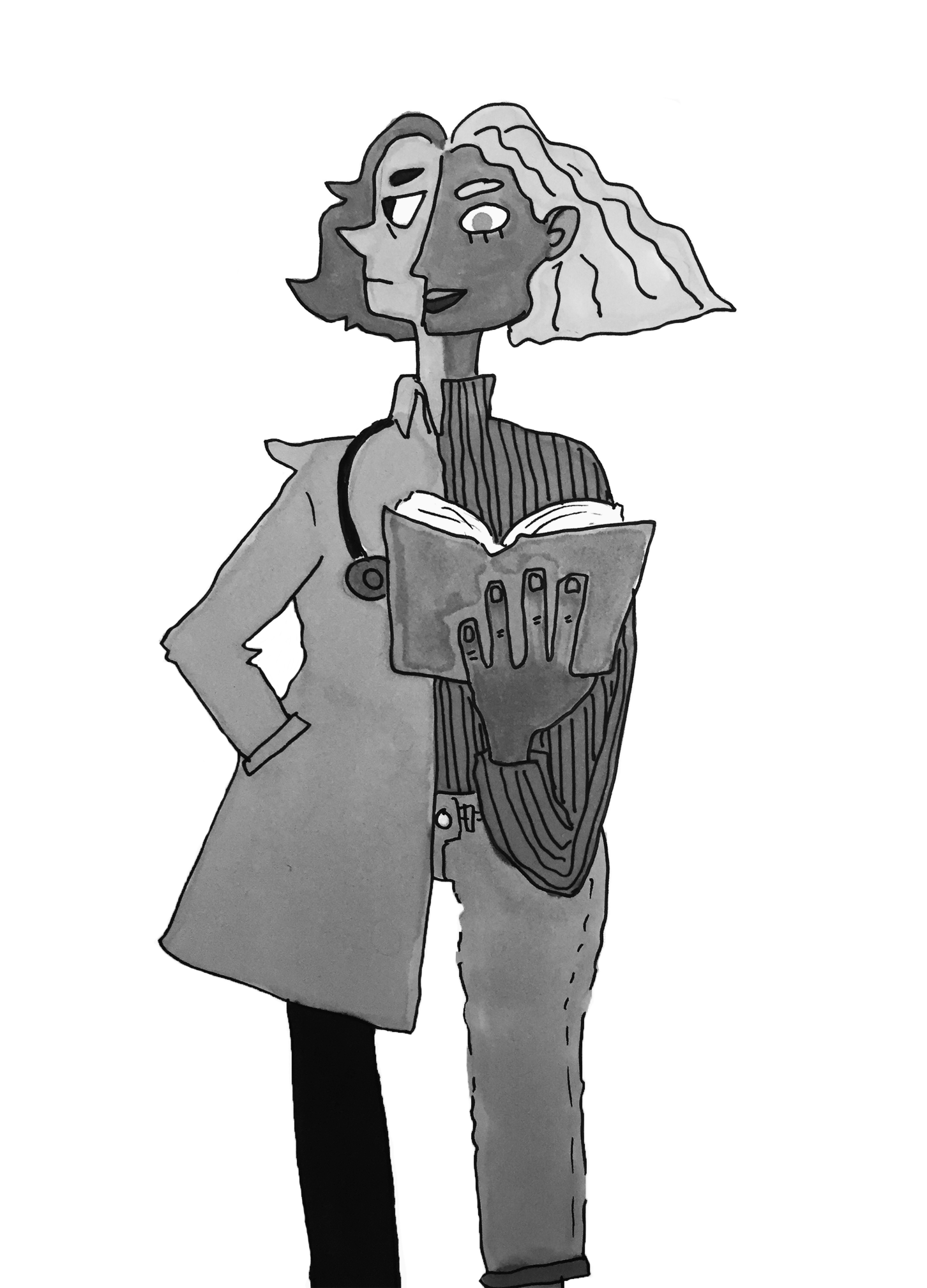

Last semester, an English professor asked me what I wanted to do with my life, and I said exactly the wrong thing.

I want to be a doctor, I said. Then, after I retire, I want to write.

So you’re using your second-best mind for writing, he said.

At that moment, I didn’t know how to answer. I’ve never been good at instant explanations, and it was one of those snappy sound bites that strike straight to the bone. Even now, just thinking about it, I remember the hot flush of my face, the sudden, jarring intrusion of tears. I wanted to lash out, but I also wanted to bite my tongue. I wanted to justify myself, but at the same time say absolutely nothing. I was glad when someone changed the topic.

Since then, I’ve been replaying that conversation. I’ll probably never see this English professor again, but I can’t help but believe that things were left unfinished, that if I had a second chance, I could do much better this time around. I want to have an honest talk with him without the presence of my classmates. This is a story that isn’t really meant for public places.

I want to tell him that writing has never been a right to me, it has always been a privilege. I grew up in a household that treated writing at best as a hobby and at worst an extracurricular that made me a more interesting person in my college applications. This is not to say that my parents were not supportive of my writing — to a certain extent. They read my articles, my short stories, drafts of novels with the kind of pride that only parents can have for their children’s work. In college, when he had to write about a book, my father would read the first chapter and the last chapter and write exactly the minimum number of words required. He said that my novel was the first book he had actually completed, first page to last page, without it being mandatory.

However, I keep thinking back on the summer after my junior year. I applied to The Kenyon Review Young Writers Workshop, and much to me and my English teacher’s delight, got in. When I told my mother about it — and the $2,375 price tag — she pursed her lips. We were buying a new house at the time, much closer to my high school. She told me to choose: the house or the workshop.

I chose the house.

That was probably the moment I knew that writing as a career was dead to me — or, at least, dead in the sense that I would have to forgo any financial support if I wanted to pursue it, for college and for the future. But, let me make it clear, I don’t want your pity. I know this narrative far too well, I’ve seen it played out far too much in literature and on television screens. It’s easy to villainize my parents — the Tiger Mother, the Tiger Father, me the hapless victim of cultural oppression — but I’m not suffering from Stockholm Syndrome. It’s taken me a while, but I think I can finally guess why.

Like most parents, my parents have always wanted the best for me. The fact that I’m able to write this right now for the Yale Daily News is testament to that fact. But I don’t believe that their measures of success are rooted in just how big my paycheck will be in the future. I have to remember the country they came to and the country we now live in. I must remember that when my mother asked her advisor at Purdue University to write her a recommendation letter, he deliberately wrote poorly about her. I must remember that because of my father’s heavily accented English, he left the United States and took a job in China instead to better support our family. I must remember these and many other moments because I think everything they have done for me boils down to a desire for me to be heard.

After all, when you have a degree, people must take you seriously. When you have an M.D., you must have something important to say. Perhaps their greatest fear for me as a writer was that I’d end up a solitary voice, howling in the wilderness.

This is a terrible fear for any parent to have for their child.

I said before that my parents supported my writing to a certain extent. Yet, I have to wonder if our circumstances had been different, how my life — a life as a writer — would have played out. I’ve seen my parents read my work, the way they’d print out my articles, collect the magazines I’ve published short stories in. I remember this moment, when I was in fifth grade and I had published my first piece of writing in a local kids’ newspaper called Bear Essentials. It was an interview with Christopher Paul Curtis, and there was my name, right in the byline. We drove to the nearby library, and my mother collected 20 copies. I would not be surprised if they were still somewhere in my house today.

It’s difficult to reconcile these two facts: the blunt practicality of my parents’ decision and the love I see when they read my writing. I sit here right now, as a molecular, cellular and developmental Biology major. I sit here right now, knowing that somewhere on a computer there are tapes of me acting out stories with stuffed animals and pillow forts that my mother likes to play from time to time.

I can only ask you not to judge us.

Contact Alice Zhao at alice.zhao@yale.edu .