Was I Raped?

On a crisp morning in Dec. 2015, I woke up alone in my freshman dorm at Yale. My bed was empty, my clothes were missing and I had a bruise on my thigh I didn’t remember getting. But then again, I didn’t remember getting home, either.

Panicked texts from friends filled my phone screen; they remembered more of the night than I did — my stumbling and slurring, my throwing up in the bathroom, my crying. They remembered the “I don’t want to do this. I regret it already.” They remembered the stocky brunette — we’ll call him Michael — I’d brought home with me.

They remembered that I went back to my room with him even though he was the same brunette who’d once grabbed me on the dance floor at a New Haven bar, who my male friends ushered me away from if we got too near while crossing campus, who had verbally harassed me earlier that week.

No one knows much of what happened after my door swung shut, except maybe him. The next morning, I just knew I was in pain. I pieced it together through the torn condom wrapper on the floor, the pictures on my phone, the delicate but urgent recollections of my friends. Later that day, as I lay looking up at fluorescent lights in Yale Health’s gynecology office, my feet in cold stirrups, the clinician — seeing severe physical trauma — asked if I’d been raped.

I didn’t know what to tell her.

I had become a member of Yale’s most secret society. It is a society of individuals with experiences that fall on an ambiguous spectrum of sexual misconduct. People who know their consent was unclear, but — because of cultural scrutiny, vague definitions and an institutional method of trial and expulsion whose reputation ranges from deeply secretive to wildly inept — don’t know if they can or should say anything, or even if what happened to them qualifies as assault.

Finding the Answer

So began my final project for Yale’s ENGL 467 seminar, “Journalism,” the capstone project of which is a magazine-length piece of investigative journalism, usually on an issue in New Haven or at Yale. It is an intensive tour of the tenets of journalism: fairness, skepticism, holding accountable those who have, in some way, failed the public. To be a journalist is to examine, expose and, hopefully, effect change.

When the seminar started in August, I had learned to ignore the nagging uncertainty about my December experience — I avoided the parties frequented by Michael and carefully monitored my drinking so I wouldn’t experience a blackout again. But around the same time pitches for our final project were due, I ran into him at a party.

Shaken, I recounted the story to a friend who is a Communication and Consent Educator. CCEs are mandatory reporters; if they hear of someone’s experience with harassment or assault they are required to tell, in the case of undergraduates, Angela Gleason, the Title IX coordinator for Yale College, who would follow up with an email. It is up to the student whether or not to take action. The friend also recommended I visit the Sexual Harassment and Assault Response and Education center.

The SHARE counselor I met with agreed with my friend — my blackout-infused hookup could certainly be considered assault. A week later, so did Gleason. A no-contact order on Michael, a mediated conversation during which I could express my discomfort and uncertainty to him or a formal Title IX complaint were all options she suggested. Unsure at the time, I did nothing; she promised to follow up a few weeks later and did.

But I did not respond, for as the semester marched forward, I remained unsure of how to label my experience, especially because I had been under the influence of alcohol. I was afraid of what would happen if I were to name my possible assailant, who is friends with many of my friends. For as many people who thought this experience qualified as assault, there were others who told me it was a regrettable byproduct of college hookup and drinking culture — unfortunate, but not catastrophic.

I was increasingly unsure of my status in the realm of sexual assault at Yale, confused and frustrated by the ambiguity. Why couldn’t anyone just tell me if I’d been assaulted or not? So when I was given the chance to write a magazine feature for “Journalism,” I jumped at the opportunity to spend two months investigating sexual misconduct at Yale.

There were two foreseeable problems with this decision: one, the question driving my inquiry was intensely personal — was I raped? At the end of this article, I thought, would be the answer that still eluded me. The second problem was the role of journalism itself, with its apparent conflict between objectivity and empathy.

The article I wrote as a journalist and the one I needed to write as a woman were two very different stories. This is a combination of the two: not traditional journalism, but a reflection on my experience, with the voices of those who spoke to me and the findings of my investigation. My hope is that this will elucidate the challenges associated with covering assault as a journalist, with defining assault as a potential victim and with provoking conversations that lead to meaningful change.

Follow the Story

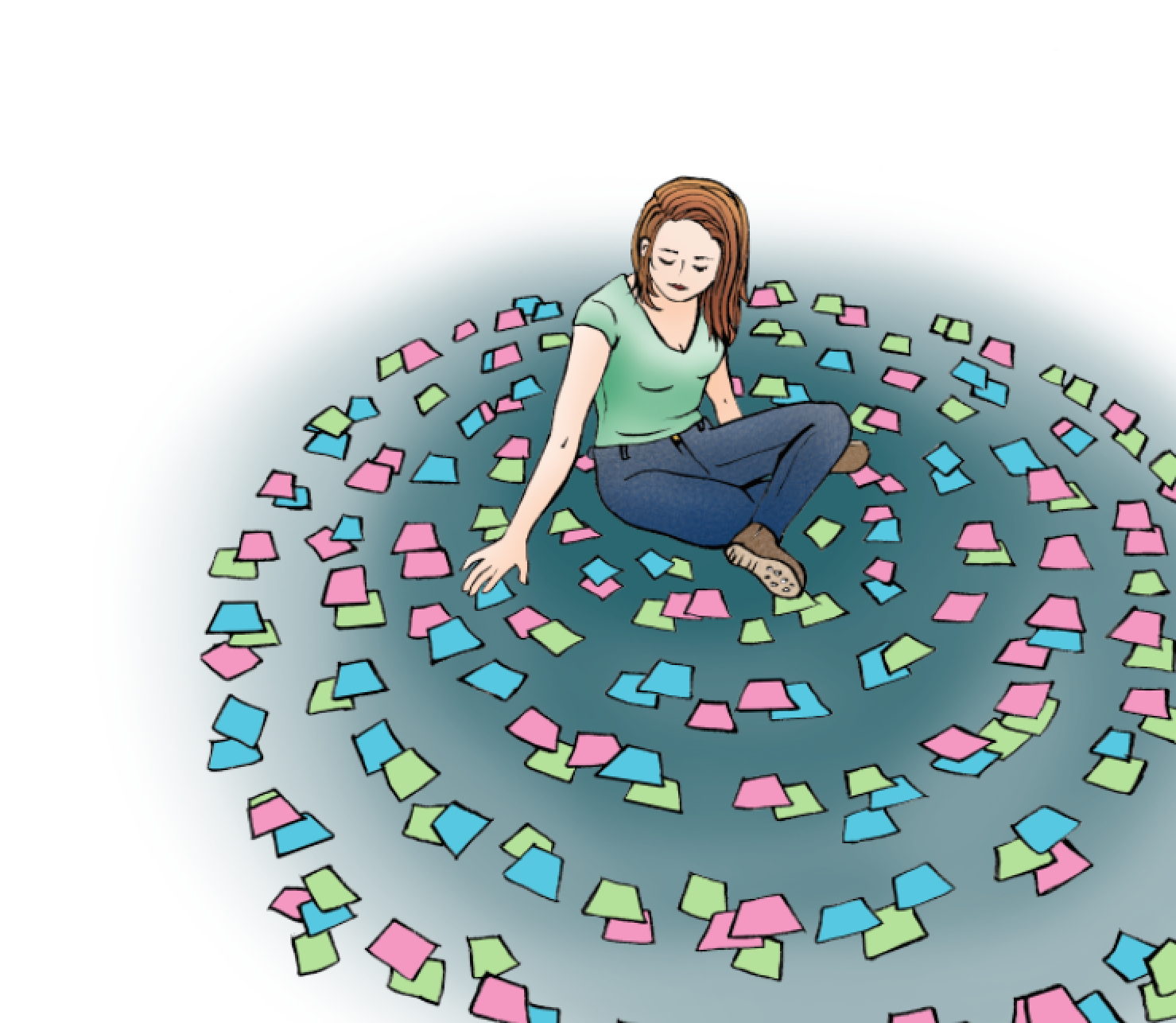

For the first month of “Journalism,” my dormitory wall was covered in colorful sticky notes outlining events indicative of Yale’s apparent culture of sexual disrespect. Green sticky note: in 2008, members of Yale’s Zeta Psi fraternity held up a sign reading “We Love Yale Sluts” outside the Yale Women’s Center. Pink sticky note: in 2009, 53 freshman women were rated on desirability — and the number of drinks it would take for someone to find them attractive, including “blackout” — in a widely circulated email (the authors of which remain unknown) to the Yale undergraduate community. Blue sticky note: in 2010, members of the fraternity Delta Kappa Epsilon marched through Old Campus chanting “No means yes, yes means anal.”

Pinned up beside the sticky notes was the 2015 survey from the Association of American Universities that reported alarmingly high statistics about campus assault: Yale’s rate of misconduct exceeded the average of the 27 schools surveyed. According to the survey, a quarter of Yale undergraduates had experienced sexual assault, and 74 percent of undergraduate women had experienced harassment. Last year, when the statistics were released, they provoked a campuswide reaction and review.

But these publicized scandals and distressing numbers weren’t the end of the story — in fact, the more women I talked to, the more I understood that my “gray area” experience with Michael (was it assault or wasn’t it?) was not the exception, but the norm.

“When you get a group of women together, so often it will just turn to talking about this sort of stuff,” said Helen Price ’18, the co-founder and director of the advocate group Unite Against Sexual Assault Yale. “Almost everyone, even if they don’t call it sexual assault, has had some sort of really horrible gray area experience. And it’s so fucked up. It’s like everyone’s a member of this secret, fucked-up little club that no one talks about until you’re part of it.”

Imagine getting together with your girlfriends — perhaps at a dining hall table, perhaps for wine on a Friday night — and bringing up an experience you had one Saturday evening. Perhaps the experience was ambiguous. Perhaps it wasn’t. You mention a name.

“Oh, you were assaulted by that person too? So was I,” your friend says.

That kind of exchange happens “all the time,” said Sonia Blue ’18, a member of USAY, which was formed in the wake of the AAU report. The people around this table — often women, but certainly not always — belong to a Yale society more secret than Skull and Bones: the “secret club,” a term used by multiple people I interviewed to refer to those whose experiences involved dubious consent, but were not clearly assault.

Still, others said the story of sexual assault at Yale had an entirely different set of victims. According to Stuart Taylor Jr., the co-author of “The Campus Rape Frenzy: The Attack on Due Process at America’s Universities,” the problem is not the apparently high statistics around assault, but the institutional targeting of accused men, and methods of trial and expulsion that favor the accusers. Yale’s University-Wide Committee on Sexual Misconduct, which is responsible for hearing cases and inflicting punishment, is a “grossly unfair” way of handling campus assault, Taylor says. The lack of clear legal proceedings — no recordings of procedures, public documents, a jury of one’s peers or a clear definition of what constitutes misconduct — makes it a “cure that is worse than the crime,” he added.

As I interviewed and investigated, I found that almost everyone agrees that there is “something sick going on at Yale,” in the words of Taylor — but what constitutes that sickness is more uncertain. Those who have gone through the UWC process as accusers (predominantly but not all women) feel the Committee fails to adequately punish assaulters. But others who’ve been accused or simply watched proceedings from the outside feel that the UWC acts on a singular desire to expel men — especially athletes — at the first glimmer of wrongdoing in a rushed, secretive and biased process.

And, at the intersection of both viewpoints lies a confusion about what constitutes consent and qualifies as assault: women wonder if they’ve been raped, men wonder if they’ve raped someone. For something as life-altering as sexual misconduct, or allegations of it, the ambiguity is intolerable.

Consenting While Intoxicated

This clash of opinions itself demonstrates the ingrained difficulty of addressing issues of sexual misconduct on campus — everyone feels targeted by a system that consistently fails them. But as I waded further into the investigation, more profound ambiguities emerged — ambiguity of whom this affects, what happens to them and why. At the center of the ambiguousness of my experience and others’ is the question of consent.

Every freshman at Yale attends a workshop with CCEs who make clear that, for any sexual experience, consent must be “positive, unambiguous and voluntary.” As part of this workshop, CCEs specify that consent is not the absence of a “no,” but the presence of a “yes.” Furthermore, CCEs and Yale’s Sexual Misconduct Response website specify that consent is unobtainable from someone who is “mentally or physically incapacitated, whether due to alcohol, drugs or some other condition.” The website goes on to define incapacitation as the lack of ability to make decisions regarding one’s own sexual activity.

Was I incapacitated that December? Did I consent? Could I have? I was in a state of “blackout,” which happens when one has consumed enough alcohol that the hippocampus stops being able to produce memories, preventing an individual from recalling anything. The confounding factor, however, is that even if someone is in the state of blackout, they can still be fully operational — talking, laughing, drinking more and, indeed, having sex as if they are only minimally drunk.

One CCE I spoke with said you can be drinking, but not be incapacitated and still give consent. When is someone incapacitated? According to that CCE, incapacitation falls “somewhere along the spectrum” of intoxication such that an individual might slur their words, forget their location or not remember their name. At this point, an individual cannot consent.

“Incapacitation is a [Blood Alcohol Content] that changes from state to state, and CCEs generally don’t give that number because it’s not about separating out gray cases in the workshop so much as saying ‘you should know better,’” the CCE said, referring to the early-year workshops conducted for freshmen and sophomores. “Blackouts are different — they’re about spikes in BAC and not level, correlated but not always. But memory loss makes everything incredibly tricky.”

UWC Chair David Post told me that cases of incapacitation are some of the most difficult ones handled by the UWC. In these cases, the burden falls on the UWC panel to decide if there is a “preponderance of evidence” to suggest that a person was drunk or otherwise so impaired that they could not consent.

“Each case is different and there is no single factor used to determine if a person was incapacitated,” Post said.

But if you’ve assaulted someone, alcohol isn’t an excuse: there is one standard for hearing consent across the board, drunk or not, according to USAY board member Lindsey Hogg ’17. Indeed, because of a lack of language for the spectrum along which sexual assault can fall, Hogg said she has had men — fraternity brothers and male athletes especially — come to her with a worrying question: “Did I just rape this girl?”

“That’s such a big, terrifying word to say, to tell people to label themselves as a rapist,” Hogg said. “We don’t have a breadth of language to talk about these experiences, [and] we don’t have a label for someone who has assaulted someone non-violently. It’s better to label everything under an umbrella to avoid a gray area, but I think what we’ll see is more of a nuanced language form around these things. The only answer I see right now is we have to be more comfortable labeling things as assault, to support people who want to identify as survivors and just rolling with that.”

Another Story

As prevalent as the secret club is the problem of men — especially male athletes and fraternity brothers — who feel targeted by the UWC. Cases of sexual assault that are elevated to a level of national interest tend to involve prominent athletes — consider Brock Turner, or Jack Montague — and fraternities have endured a near-constant wave of scrutiny, at Yale and beyond, for apparently fostering environments in which sexual assault isn’t only common, but condoned. One current Yale male athlete I interviewed, who requested anonymity, said that prior to attending Yale, he was warned by family friends to be “incredibly careful” in his interactions with women because of perceived bias against male athletes.

“If you make a mistake, from the guy’s perspective, you’re put in a way tougher position because they tend to side with the girls,” he said. “It’s scary sometimes, for the guy. Nothing is written down, nothing is being recorded. All that people have to judge you on is what is said from the case. Let’s say you have consensual sex with a girl, and she then changes her mind because she doesn’t like you or she regrets it — that’s a threat. That’s very scary, even though you’ve done nothing wrong.”

This perspective is crucial, and organizations like USAY have worked to include groups of men in the conversation. Max Cook ’17, the former president of Yale’s Sigma Nu fraternity, as well as a member of USAY and Yale’s soccer team, said that members of his team have felt frustrated by public opinion pieces that blame rape culture on male athletes, while simultaneously excluding them from any productive dialogue. Cook described this as a “flaw in activism.”

“How are you supposed to fix a community that you deem to be unhealthy if [male athletes and fraternity brothers] are never involved in conversations about how this campus works or how to do better?” he asked.

But, with only three exceptions, most individuals in fraternities or on sports teams that I reached out to declined to comment for fear of having their words twisted, being associated with issues of assault or because they had been treated poorly by journalism in the past. I turned to friends, journalists who — though they usually attempted to be helpful and cordial — also ultimately declined. A few male friends even expressed wariness about my intentions: my role as a journalist twisted their faith in me as a friend, which perhaps was deserved, but still concerning.

And, even after writing and researching the story, I still couldn’t determine whether this perceived bias was real or deserved. Women I interviewed felt the odds were stacked against them in disciplinary proceedings, and prominent men on campus were more likely be pardoned, or given a lighter punishment.

“With athletic teams, there’s a lot of complacency that goes on. It’s still this boys club, and it’s allowed to be that way because they’re athletes,” one anonymous woman said. “[Fraternities and athletes] need to be held accountable. So many times they just aren’t, which is why I was so fucking shocked they did the right thing with Montague.”

Another woman I interviewed told me that she sees a “a strong culture of entitlement here, where people feel like they deserve things just by the nature of being privileged white men [who] are a very predominant group [here].”

“I feel like it’s not like they would ever necessarily force someone into doing something they wouldn’t want to do, it’s that they wouldn’t expect that someone wouldn’t want to do something,” she said.

Unanswered Questions

Early on, I interviewed a Yale woman who was assaulted her freshman year and subsequently encountered delays as she attempted to report her rape to the Title IX coordinators. As we talked, and she told me about her experience, I felt the journalistic armor of a tape recorder and reporter’s notebook slip away. I was a woman, and I was angry. I didn’t want to ask questions — I simply wanted to sit and cry and commiserate about the bad things that happen to our friends and sisters in dark rooms that no one ever talks about. I left the interview and cried quietly on a sidewalk corner.

I wrote this woman’s story into the first draft of my article for “Journalism.” In the margins, my professor wrote, “How do you know this?” The comment was fair: in the wake of the now-infamous Rolling Stone article “A Rape on Campus, Nov. 19, 2014,” which did not corroborate an alleged campus assault and led to the subsequent legal and journalistic downfall of the author, journalists are hypersensitive to the possibility of conflicting stories, lies and sources who lead them astray. It is unacceptable to publish an anecdote without the qualifying “he said” or “she said,” and preferably copies of official documents or emails, along with responses from the assailant themselves.

Equally unacceptable, of course, was how I wanted to respond to my professor’s inquiry: “I know because I know. I know because I hear the fear and the anger and the betrayal in their voices. I know because I, too, have been there.” The answer is as ineffective in a classroom as it would be in a court of law, but it felt invasive and insensitive to return to the women who had trusted me with their most traumatizing life experiences and request corroboration. To do the job of a journalist, I had to abandon an empathy that drove the story in the first place.

For this reason — and for others — writing about sexual assault is a prodigious and urgent challenge. Reporting can be emotionally brutalizing, especially if your head and your heart — your role as a friend and your role as a journalist — are in direct conflict. For the duration of “Journalism,” I cried all the time. I relived December over and over again every time I wrote a paragraph or transcribed an interview, and became restless with frustration. And still, the question that had been lingering in my head for nearly a year — the question that drove the story in the first place — remained unanswered: was I raped? That made the whole process of inquiry even more irreconcilable — who was I to feel the pain of the people I interviewed? Who was I not to? Was our pain the same?

In the end, the article I submitted for class was lifeless under the scrutiny of corroboration, lacking the power I had hoped it would carry. What was demanded of me by the standards of journalistic integrity also demanded that I sacrifice the humanity that had compelled me to write in the first place. Retrospectively, I chose the wrong thing to write about — I was never going to be unbiased. I was in it for myself — to find out if I had been assaulted — as much as I was in it for the story or the grade. I chose this topic because I wanted to write about something to which I could devote myself completely; I wanted to become obsessed, and I did, except the passion that drove me was coldly absent from the ultimate product.

But maybe these stories — stories about humanity, its fragility and the shocking chasms opened up by lack of communication — would be improved by a little more selfhood and empathy between the lines of journalists’ articles. People didn’t want to talk to me in my capacity as a journalist, and in truth, I wouldn’t have wanted to talk to me either. The very question “can you prove to me you were assaulted?” would set me reeling; telling a journalist what you might not disclose to a close friend seems inconceivable.

Stories are crucial in provoking dialogues, but my impression is that journalism has been ineffective in solving this problem: campus assaults, or “gray area experiences,” happen all the time no matter how often The New York Times or the News publishes another story detailing a flawed disciplinary process. It’s the heartfelt recognition of painful human experience that makes conversations worthwhile, and I believe more conversations like these will increase empathy in the cultural dialogue.

Here’s the other crucial thing: this story is a small piece in what must be an ongoing and acutely sensitive discussion. This story is a fraction of a breathlessly big problem, and the stories that we need to make room for are about the extremely high levels of assault and harassment happening to queer or transgender individuals, the frightening impact race has on who’s assaulted and how those cases are treated by the UWC. It’s essential to tell those stories — for me, for everyone. Luckily, I have immense faith in the future of journalism, and in my peers, to continue this dialogue in new and empathetic ways.

Rape is a real problem on Yale’s campus, and I have felt myself recede inward as a result of the crippling helplessness that this culture of disrespect demands. But we can’t retreat into ourselves and hope it gets better — I’m done feeling small. We have to talk and exercise understanding and hold each other accountable. If you’re in a meeting of the secret club, offer support and solidarity, whether you’re a member or not. Advocates, USAY, CCEs, SHARE, others: keep doing your thing, because we need you, badly. And for all of us: let’s think, empathetically, about how what happens on a Saturday night affects the way we exist in this place we call home. Maybe I didn’t walk away from this story with answers, but I walked away knowing that we can do something, and the conversation has to start now.