Mohamed Hafez paced around his cluttered studio at 909 Whalley Ave. as he discussed his native Syria. “I am an architect, so I know how buildings fall apart,” he told me.

As he spoke, Middle Eastern music played on loop in the background. Stacks of cardboard boxes brimmed with metal gears, rock chunks, decomposing radios and toy cars. Wrenches and graphite sketches covered every inch of the wall — printed photographs of the aftermath of Aleppo bombings hung alongside Hafez’s sculptural renderings. Red flowers — representative of martyrdom — and dirtied scraps of fabric were interwoven into models of Syrian city ruins and paired with Quranic messages of hope. The pieces showed the intersection of Hafez’s architectural knowledge and Syrian pride. Using found objects — many from junkyards or donated by his admirers — Hafez constructed landscapes with dollhouse furniture, metal piping, Styrofoam and ingenious layering techniques.

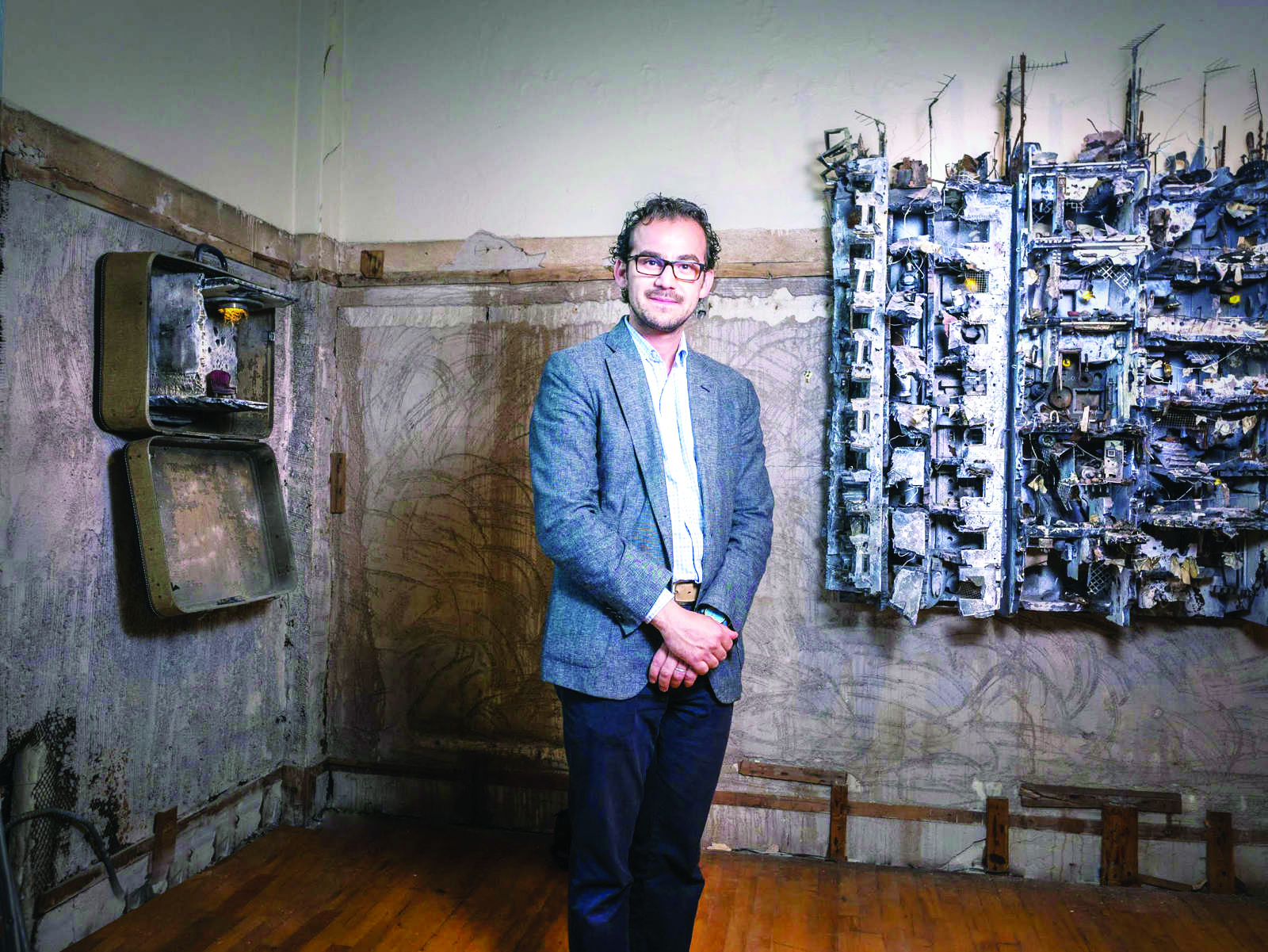

Although his studio seemed dysfunctional at first glance, there was a sense of controlled chaos. His walls were full but the floors were clean, his workspace overflowing but the storage area tightly organized. A soft-spoken but serious artist and architect, Hafez dressed smartly, carrying himself in a way that made people want to listen to him without ever needing to raise his voice. He was clean-cut and steady, but his eyes were troubled while discussing Syria’s devastation.

In 2011, a year before the Syrian Revolution erupted as part of the Arab Spring, Hafez visited his family and noticed a growing sense of unrest among the civilian population. Now, in 2017, the bloody civil war that followed the revolution has been raging for six years. Violence initially broke out when Syrian President Bashar al-Assad cracked down on protests, and the conflict was further spurred on by existing ethnic and religious divisions. Full-fledged war commenced in 2012, and many other countries such as the United States and Russia became involved in what some have described as a pseudo proxy war. According to the nonprofit media campaign IAmSyria.org, 450,000 people have died in the conflict and tens of millions have been displaced — some of whom are Hafez’s friends and family. As Hafez watched the horrors from afar, the destruction of Syria and its people became the centerpiece of his work.

By day, he does corporate work at the architectural firm Pickard Chilton, but Hafez said he makes art to stay sane. He was born in Damascus, the culturally vibrant capital of Syria. When he was a child, however, Hafez’s father relocated the family to Saudi Arabia for 14 years. Still, he considers Syria his home and later returned as a young adult. Fiddling with a square of purple architectural foam between his fingers, his gaze was steady when he discussed his nostalgia for old Damascus and the rich array of intersecting Biblical, Roman, Greek and Islamic architecture. When war bombings destroyed some of these buildings, he grieved for their loss.

—

Mohamed Hafez moved to the United States to pursue an architecture degree at Iowa State University. It took him over a year and a half to receive his student visa, and that was only after he contacted his embassy officer several times and was repeatedly told that his application was “in process.” At the time, Syrian students were only eligible for single-entry visas. Fearing he wouldn’t be able to receive a return visa to the U.S., Hafez was unable to visit his family in Syria for eight years — he was only able to go back when he became a naturalized U.S. citizen. He spoke with a somber voice when he described his overwhelming homesickness for Syrian culture and people.

As a practicing Syrian Muslim student in Iowa, Hafez found little to do for recreation; he laughed as he described his adherence to the Islamic policy of alcohol abstinence. It was during this time that he created his first piece of art, an untitled, simple scene of a Syrian doorway. “The work always started as a personal refuge [from my homesickness], and it continues to be that,” he said.

Later on, Hafez found it heartbreaking to witness the physical deterioration of his country during the Syrian Civil War. He mourned both the human tragedy and the loss of many priceless archaeological sites that could never be repaired. Through his work, Hafez attempted to preserve aspects of his homeland, using recorded sounds from the balcony of his old residence in Syria, markets, courtyards and public spaces. It is through multiple dimensions that Hafez expressed his deep love for the Syria he left behind.

One of his pieces, “Between Love and War,” explored the relationships lost after the destruction. Aspects of traditional Syrian architecture overlapped with objects of war, instilling a sorrowful sense of contrast within the piece. Hafez started the piece with basic sketches, but the work expanded organically as he worked. Purple architectural foam slathered in paints of varying shades of gray formed the basis of the structure. He then added and subtracted found objects such as radio bulbs to represent a hanging light, and a dish strainer to act as window screening. He threaded dried anemone flowers through the rusted metal, bright-red and brave against the rubble. “Between Love and War” formed a visually striking street scene of Syria.

Courtesy of Mohamed Hafez.

—

Hafez’s usual composure broke down when he talked about his home. He continually passed his eyes across the deconstructed pieces hanging on his walls, his hands fidgety and eager to work. The newspapers don’t tell stories about individuals, he said while tugging at the loose strings on his sweater. They tend to extrapolate upon numbers and statistics, capitalizing on the images of nameless, identity-less children who have been displaced. But Hafez was honest and spoke eloquently, claiming nothing but his own story.

Damascus in the 1990s was bustling, he said. It was the true city that never sleeps — people go to bed at two or three in the morning and wake up early the next day for work. Unlike the “fast-food, fast-life” attitude of New York City, Damascus culture prized time spent with family and friends. Dinner can last as long as four hours, during which people sit around the tables and voices fly in a cacophony of exchange and love. Hafez described his memories of Damascus as unsettled nostalgia, as he longed for a city that no longer exists with the same fabric. “I miss the simplicity and joy of life,” he said. Hafez was fortunate in that his area of town in Damascus escaped total destruction. But for cities like Aleppo, “it will take generations to forget,” and decades of institutional reform to physically rebuild.

Hafez mourned the death of the country he once knew, now in such devastating conditions. “Think of the children that did not live [Syria’s] glory. All they have experienced of their country is war,” he said. “The institutions have failed us. … It’s a shame in humanity’s record that we allow a disaster like Aleppo to happen again and again.”

The tragedy in Syria has extended well beyond its borders — the massive flow of refugees from the country following the outbreak of war has become an alarming international issue, and often a political one. Under the Obama administration, the United States responded to the crisis by accepting increasing numbers of Syrian refugees — a total of 18,000 arrived between 2011 and 2016 — and setting a goal of 110,000 resettlements. But recent executive orders issued by President Donald Trump have put these refugees at risk. On Jan. 27, 2017, Trump put into place a system of filtering that he referred to as “extreme vetting.” Those from “terror-prone” nations — including Jordan and Syria — were prohibited to enter for 90 days, and the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program was suspended entirely for 120 days. Trump also lowered the 2017 goal of resettlements from 110,000 to 50,000, setting off a chain of legal chaos and general confusion.

Hafez shared his concern about the gradual strip of human rights, and the increasing “radical rhetoric” that acts as a breeding ground for government authoritarianism in both Syria and the United States. The resulting marginalization of minorities consistently appears throughout his work. He emphasized the importance of viewing refugees as equal humans, with the same hopes and dreams. Rather than giving up in the wake of troubling times, he insisted upon augmenting activism efforts and engaging in productive dialogue. He pointed to factionalized discourse in the U.S. “People don’t know about a lot of us, you know?” He smiled, slightly exasperated, as he mentioned how people are always shocked that his mother is blonde and doesn’t wear a hijab. Fumbling with a square of purple Styrofoam, Hafez crinkled his eyes faintly as he openly discussed his views on the differences and similarities between the American and Syrian governments.

However, when asked about his political opinion of the newly elected Trump administration, he fidgeted and was reluctant to respond directly. “You know, I don’t like going into politics,” he hesitated before going on. “I am a Muslim-Syrian artist, and I do not feel safe expressing my political opinion. Write that down.”

While Hafez isn’t a refugee in the legal sense of the word, he said he shares a similar sense of displacement. Hafez described his feeling of rootlessness as “disturbing,” knowing he is a citizen of two countries: one of which has crumbled into ashes and another which does not welcome him. And, perhaps more than anything else, this is why he makes art — to reconstruct his own identity and to explore the culture of refugees and disconnect between Syria and the United States.