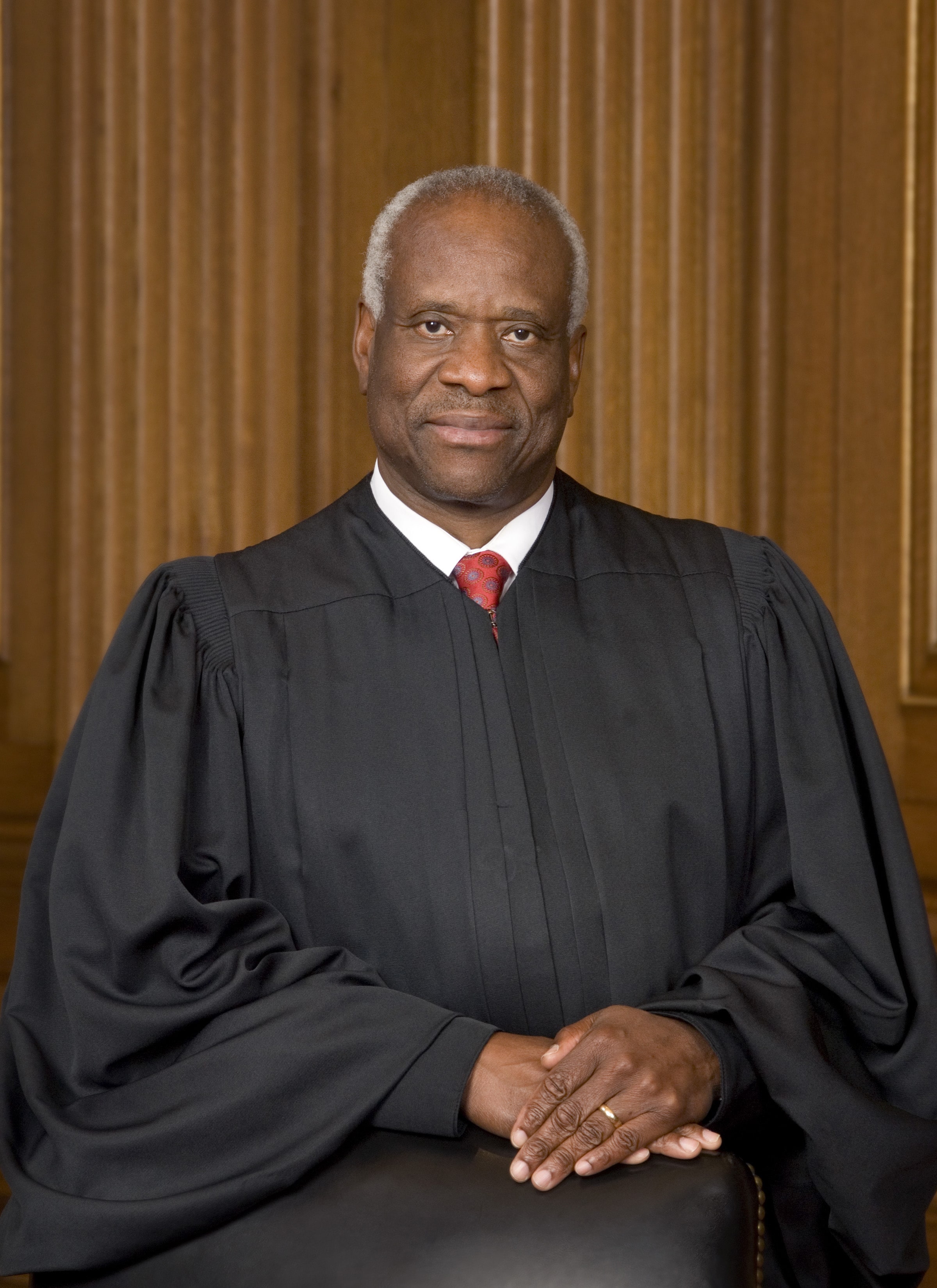

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The Yale Federalist Society and Yale Law School co-hosted a conference in honor of Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas LAW ’74 on Feb. 10–11.

Marking a celebration of Thomas’ 25 years on the Supreme Court, the conference attracted students from universities and law schools across the country. Thomas, who had expressed ire toward Yale in his autobiography “My Grandfather’s Son,” returned to campus to share his experiences before and while serving on the Supreme Court. Attendees interviewed said they admire Thomas and his originalist interpretation of the Constitution.

“I think it is really timely because as people have concerns about the actions of individuals in government, there has been a lot of interest in constitutional limits on government and how the courts can protect rights,” said Will Simpson, a conference attendee and third-year law student at the Boston University School of Law. “I think this conference comes at a really timely moment for popular interest and non-legal interest, and what these judges do.”

Thomas was born in a small, predominantly black neighborhood near Savannah, Georgia. Growing up as the only black student in his grammar school — and the first in his family to attend college — Thomas developed compassion for black youth, saying that his position in college, rather than in prison, was a fortune and a privilege. Panelists who had clerked for Thomas previously, such as William Consovoy and Nicole Garnett LAW ’95, a law professor at Notre Dame Law School, noted that the empathy Thomas demonstrated contrasted sharply with the image of a “cruel” judge that others projected on him.

An originalist interpretation of the Constitution focuses on the original intent of the writers and framers of the Constitution, as opposed to judicial activism, which can involve personal or political considerations. Thomas has been hailed as a staunch defender of originalism.

Regarding the conference’s timeliness, Garnett speculated that the public might see recently nominated Judge Neil Gorsuch espouse similar views to those of Thomas, but added that it is too early to tell.

Simpson said he admires originalism, highlighting Thomas’ commitment to a “stable written word of law.”

“At minimum, I think [originalism] provides a very useful boundary for what is an acceptable interpretation,” Simpson said. “Maybe there is a range of answers within the balance between what could have been an original public meaning, and I think that really useful as far as applying and interpreting written laws.”

One topic of contention that arose during the conference, particularly during a panel on Thomas and criminal justice, revolved around the potential for jurisprudence on executive power. The panel — which featured Marah McLeod, an associate professor of law at the Notre Dame Law School; Adam Mortara, a lecturer at University of Chicago Law School; William Pryor Jr., from the U.S. Court of Appeals on the Eleventh Circuit; and Kate Stith, a Yale Law School professor — mentioned that Thomas may invoke judicial checks on President Donald Trump’s executive orders only if such a case reaches the Supreme Court.

The panel also discussed the importance of having a full court at the time of a case on executive power, to avoid a tie.

Steven Tian ’20, who attended all the panels, called Thomas a pioneer on originalism. To that end, he said that hearing from the “original originalist” was a great opportunity, and expressed optimism about Thomas’s jurisprudence under the Trump administration.

“I think one of the great things about [Thomas] is that he sticks to his guns on what he believes no matter who the president is,” Tian said. “His doctrine of originalism is very strict. And I think we have cause to hope that the Constitution will be upheld over these next four years of Donald Trump.”