The renaming of Calhoun College comes in the midst of a national discussion on building names and other historical artifacts tied to the legacy of slavery in America — a conversation that has played out differently at each school.

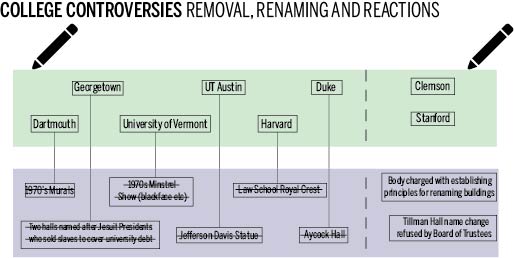

In a communitywide email announcing the name change Saturday afternoon, University President Peter Salovey said that in drafting its report, the Committee to Establish Principles on Renaming studied precedents at other schools, such as Georgetown University, Harvard Law School, Princeton University and the University of Texas at Austin. Yale has learned from these institutions while “charting its own course,” Salovey wrote.

In the past few decades, many colleges and universities have altered campus traditions and naming practices in light of their ties to racist moments or figures. Most campus conversations confronting histories of racism and protests against visually offensive signs began in the early 1970s, after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 allowed an influx of students of color to enter historically white colleges.

Educational institutions have responded to these discussions with varying degrees of engagement, and grappled with difficult question of how they can preserve history while removing its physical manifestations. Yale’s procedure in changing the name of Calhoun College, which involves preserving works of art bearing Calhoun’s name and likeness, may prove influential as other schools nationwide deal with similar issues.

“Part of the reason Yale struggles with [Calhoun] today is that it chose not to struggle with it then,” said Craig Steven Wilder, professor of history at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and author of “Ebony & Ivy: Race, Slavery, and the Troubled History of America’s Universities.”

Wilder explained that by not fully addressing the original concerns raised by Yalies in the 1970s, Yale would eventually have to come to terms with its history later on. Dartmouth College, after its 200th anniversary in 1969, addressed its early history as an academy for the education of Native Americans, Wilder said. According to Wilder, by taking the time to reflect on crucial social issues as early as 1970, Dartmouth was able find resolutions to its more glaring elements of racism on campus before they turned into prolonged conversations.

One such change, Wilder noted, came for the Hovey Murals at Dartmouth, which portray the mythical founding of Dartmouth by Eleazar Wheelock, class of 1733. The artwork controversially featured Wheelock introducing Native American men to rum and a Native American woman reading a book upside down. Dartmouth’s discussion following its 200th anniversary, Wilder explained, led to the murals’ eventual removal from public view.

Princeton recently decided to retain the names of both the Woodrow Wilson Residential College and Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs despite student protests against Wilson’s historic connection to racist government policies. But every case is different, and the analogy between Woodrow Wilson and John C. Calhoun, class of 1804, is not a simple one, Wilder said.

“Wilson’s legacy on our campus and beyond is very different from Calhoun’s legacy in this country and at Yale, and that led to different outcomes in applying similar principles,” said John Cramer, Princeton’s director of media relations.

At Georgetown University, two buildings, Mulledy Hall and McSherry Hall — both named in honor of former Jesuit university presidents who had organized the sale of slaves in order to pay off-campus debt — were renamed, respectively, after Isaac, the first enslaved person noted in the records of Georgetown’s slave sale, and Anne Marie Becraft, a free woman of color who founded a school for black girls near Georgetown in 1827.

University of North Carolina recently changed the name of Saunders Hall, named for a former KKK leader in North Carolina who served as a university trustee, to Carolina Hall. Additionally, taking heed of concerns that the renaming would lead to the erasure of important historical issues, the administration also coordinated the construction of an exhibit in Carolina Hall that contextualizes the controversial past of its former namesake.

“I’ve talked to a lot of people from some of the other campuses,” said Cecelia Moore, who heads the task force on UNC-Chapel Hill history. “There’s a way to sort of tell this history without freezing the campus in time.”

Moore explained that Saunders, like Calhoun for Yale, no longer represents the values of UNC. She added that her task force has plans to set up projects that will explore specific interpretations of the university’s history, such as with race issues in America, in order to keep telling the stories of people like Saunders without honoring their name.

Vanderbilt University removed the “Confederate” from the inscribed “Confederate Memorial Hall” on campus last year. Vanderbilt Chancellor Nicholas Zeppos publicly said the name runs against Vanderbilt’s founding values of union and healing after the Civil War.

Harvard Law School faced a similar issue over the school’s crest, which belonged to that of the family of slaveholder Isaac Royall. A successful student movement dubbed Royall Must Fall spearheaded the campaign to remove the crest from the law school.

The face of activism has varied across institutions, however. While student and community activists in various groups pushed for the renaming of Calhoun College, the student governments at the University of Texas at Austin and Duke University made the recommendations that resulted in change at their institutions.

In UT Austin, the student government voted to remove a statue of Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War. And at Duke, the student government voted to rename Aycock Hall, named after former North Carolina Gov. Charles Aycock, a prominent white supremacist from the early 1900s.

Additionally, Clemson University’s Faculty Senate and Graduate Student Government both asked their university to rename Tillman Hall in February 2015. The hall was named after Benjamin Tillman, a former South Carolina governor who espoused white supremacist ideals, advocated for the murder of black people and led efforts to institute Jim Crow laws in South Carolina during the late 19th century. The chairman of Clemson’s board of trustees, however, immediately refused the proposition.

Stanford University announced in March 2016 that it would create a committee to establish general principles to rename streets and buildings — just a few months before Salovey announced the Committee to Establish Principles on Renaming in August. Unlike Yale, Stanford’s committee has not yet released a report.

“The university’s naming committee is still at work and we expect to have a recommendation from them at end of the academic year,” said Ernest Miranda, senior director of media relations at Stanford University.

In 2006, Brown University released a report acknowledging the relationship between the New England slave trade and the university’s founding, but no peer institution, including Yale, has followed suit, Wilder said.

He added that if Yale’s administration had taken an interest in the same type of self-examination that Brown exercised in 2006, the Calhoun decision would likely not have taken as long. Instead, he added, it was left to grass-roots movements to bring about change.

For Wilder, part of the solution for universities struggling with their connections to the slave trade means coming to terms with the complete role of slavery in America’s history.

“The history of slavery is not embarrassing, the history of slavery is actually our national history,” said Wilder. “Until we can confront that reality, we’re always going to remain a divided and tormented nation.”