As the trustees of the Yale Corporation consider new measures designed to improve their transparency and accessibility, the vast majority of undergraduates remain largely uninformed about the Corporation, from the way it makes decisions to the names of its 17 members.

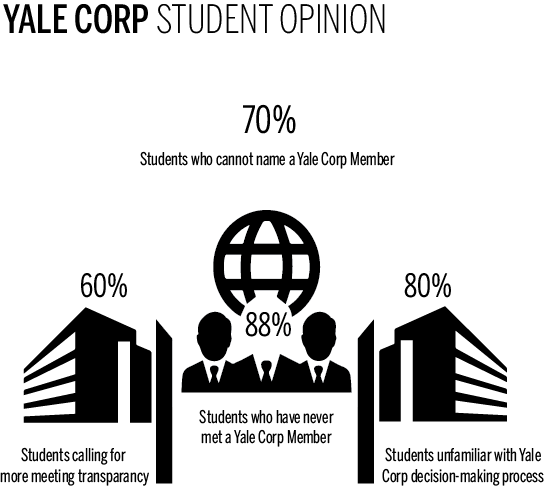

A News survey distributed in January found that 70 percent of Yale undergraduates do not know the names of any Corporation members, aside from University President Peter Salovey. Moreover, around 88 percent of respondents said they had never met a member of the Corporation, and 80 percent said they were unfamiliar with the Corporation’s decision-making process. The 806 responses represent around 15 percent of Yale’s undergraduate population, and results have not been adjusted for bias.

Last year, students complained that the Corporation was deaf to undergraduate concerns and overly secretive in its decision to keep the name of Calhoun College. But despite those complaints, undergraduates are mostly unfamiliar with basic information about the trustees that is already publicly available, according to the survey.

“I’m not sure exactly who is part of the Yale Corporation, like if it’s specific people who are involved, if it’s well-known administrators,” Duncan Moore ’20 said in a follow-up interview. “I just know that they handle a lot of the administrative technicalities.”

As the highest governing body at the University, the Corporation — whose 17 members come from academia, the business world and other industries — confers honorary degrees and has authority over Yale’s finances. Last year, the Corporation had final say over the naming of Calhoun College, the debate over the title “master” and the names of the two new residential colleges on Prospect Street.

Since the 1980s, the Corporation — which meets on campus several times a year, with its next gathering scheduled for later this month — has developed a reputation among students as a secretive organization disconnected from undergraduate life. The Corporation does not publicize the dates or agenda of its meetings, and meeting minutes remain sealed for 50 years.

In a follow-up interview, William Viederman ’17 said students can only demand so much from the trustees. For instance, they should not be expected to attend freshman orientation to explain how the Corporation functions, he said.

But, he added, the Corporation must do more to ensure that students’ voices are heard in important University decisions.

“That will make students curious and encourage students to do a little research of their own,” Viederman said.

In an email to the News, Corporation senior fellow Donna Dubinsky ’77 said she was not surprised that Yale undergraduates know little about how the University trustees operate.

“I certainly didn’t when I was a student,” said Dubinsky, who was an undergraduate in the 1970s. “I look forward to more two-way dialogue in the coming years to help bridge this gap.”

In the survey, more than 60 percent of respondents called on the Corporation to announce its meeting dates, publicize its meeting agendas and release meeting minutes. Nearly 80 percent of students who described themselves as active in the Calhoun naming dispute said the Corporation should give undergraduates a greater voice in University decisions.

“The Corporation has an immense amount of power and is not directly accountable to the student body,” Viederman said. “It feels to me like the least they can do is be a little transparent and help us understand what’s going on.”

In September, as part of an effort to reach out to Yale undergraduates, the Corporation met with a group of 30 students for breakfast at Mory’s. Around the same time, Dubinsky held an open lunch at Jonathan Edwards College that was attended by a handful of students.

Last week, Dubinsky told the News that the Corporation discussed new measures designed to improve the body’s accessibility at its December meeting. But she declined to comment on precisely what the Corporation is considering.

“They’re very positive measures moving us in a great direction,” Dubinsky said. “But until we figure out how to make it all work, we’re trying to keep it to ourselves.”