After reinstatement, what next?

In January 2015, a freshman named Hale Ross ’18 injured himself falling from the fourth floor of Bingham Hall, and then withdrew from Yale for mental health reasons, according to friends and family.

Ross, a cross country runner, was reinstated in fall 2015. But on the evening of Oct. 30, 2016, he committed suicide in his dorm room in Calhoun College.

The story of Ross’ withdrawal and reinstatement comes from multiple interviews with his father, John Ross III ’79, as well as a former teammate and two friends and classmates in Calhoun, both of whom raised questions about the level of mental health support Ross received after returning to Yale.

“I’m incredibly saddened and shocked by the fact that it seems his mental health was not made a priority and that he somehow slipped through the cracks,” said a friend and classmate of Ross’ in Calhoun, who wished to remain anonymous due to the sensitivity of the situation. “For someone who had been clearly unstable and unwell, it’s frightening to see such a tragedy still occur. It makes me all the more afraid that a student dealing with mental health issues who has not overtly expressed that he or she is struggling will have trouble finding the adequate resources at Yale to get better.”

Ross’ father — who said the Bingham incident was never formally deemed a suicide attempt — told the News that Ross was seeing a doctor outside of Yale at the time of his death. He added that although Ross had significant support from the Calhoun community, he did not know of “any other supports” his son received at Yale. Vice President for Communications Eileen O’Connor said she could not comment on the reinstatement of a specific student.

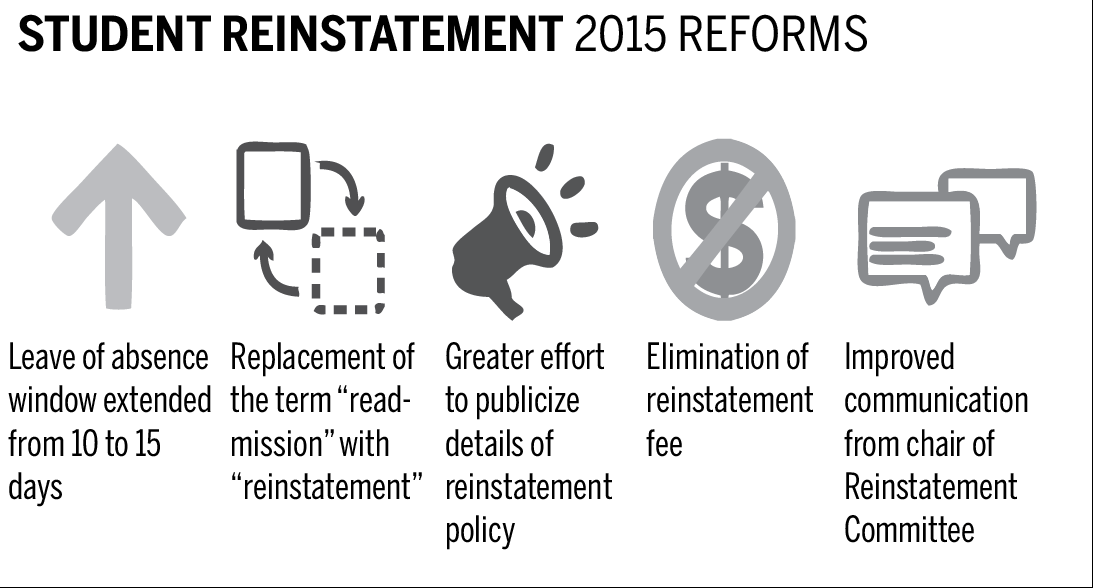

The University revised its withdrawal and reinstatement policies a year and a half ago following the suicide of Luchang Wang ’17, who, like Ross, had recently been reinstated. Those reforms focused on changes in terminology and adjustments to the timeline for withdrawal, among other issues.

But the circumstances surrounding Ross’ death have raised questions about another area of mental health policy: The support students receive following their reinstatement.

In interviews with the News, nine students who have gone through the reinstatement process for mental health reasons — some of whom withdrew after the 2015 reforms and many of whom said they hoped to shed light on a process few students understand — expressed distrust toward Yale’s Mental Health and Counseling program. Many of these students also shared concerns over the support mechanisms available to reinstated students like Ross, an aspect of the system that was not addressed in detail by the 2015 reforms.

Yale College Dean Jonathan Holloway cited the deans of the 12 residential college as the first line of support for students returning to campus, in addition to leaders of the cultural centers, Yale’s religious communities and others. But students interviewed reported a wide range of experiences with their deans, and many called for Yale to institute a more consistent support system.

“Those are the two suicides Yale has had — kids that have been gone before, not people who have never left,” said Rachel Williams ’17, who was reinstated in January 2014 after a mental health-related withdrawal, in reference to Ross and Wang. “So this whole theory that Yale has, that if [it sends] people home, they’re just going to get better, and everything’s going to be magical, and they’re going to have zero culpability, is bulls–t.”

(Ngan Vu)

A DECENTRALIZED SYSTEM

Under current Yale College policy, any undergraduate can petition for a leave of absence within the first 15 days of a new semester and later return to campus without much effort or expense. But students who withdraw — or are forced to withdraw, often for mental health reasons — after that 15-day period face significantly greater hurdles to reinstatement, including on-campus interviews and academic requirements. And once they return, the process of reintegration — going back to class, staying healthy, interacting with administrators — can present a new set of challenges.

All nine reinstated students interviewed by the News emphasized the role, positive or negative, of their residential college deans in the transition back to campus. Holloway told the News that deans are not required to meet with reinstated students, though the University has “the expectation” that they will reach out to students returning to campus.

According to student interviews, the University’s decentralized support system has led to a wide range of post-reinstatement experiences. Not every dean understands how to help students with mental health issues, students explained, and frequent administrative turnover — eight deans and heads have left their positions in the last year — can deprive students of consistent, familiar support.

Ray Mejico ’17, a member of Ezra Stiles College who withdrew for mental health reasons in the fall of 2014, described a disheartening return to campus that made him question the effectiveness of the residential college support system. When Mejico was reinstated in the spring of 2016 after a year and a half away from Yale, he said he received no institutional support from the University. Stiles was in the process of switching deans, and “there were no real resources when I came back,” he said.

Early in the semester, Mejico had coffee with the interim Stiles dean after she reached out, a gesture Mejico said he appreciated. But the new permanent dean, Nilakshi Parndigamage ’06, has not been in touch, and when Mejico met Parndigamage this fall to get his course schedule signed, she treated him like “just another face and another student that she has to push through the system,” he said.

In an email to the News, Parndigamage said she frequently meets with Stiles students who have recently been reinstated, and sometimes communicates with their parents and instructors as well. She did not comment on Mejico’s specific case.

By contrast, Eugenia Zhukovsky ’18, who was reinstated in the fall of 2015, said she had an overwhelmingly positive experience with her dean, Mia Genoni, who worked in Berkeley College until last semester.

“Me and my dean were very close and still are,” Zhukovsky said. “She reached out to me and made sure that I was OK every week. She called it a spider sense, she knew when something was wrong. She’d notice if I hadn’t talked to her for a while, she’d be like ‘are you OK?’”

Zhukovsky has stayed in touch with Genoni since the former Berkeley dean left Yale last spring to become dean of the University of Richmond’s Westhampton College. Still, Zhukovsky added that her experience with Genoni does not necessarily reflect those of most reinstated students.

“From what I’ve heard from other students and deans and their reinstatements, I think [Genoni] did that in good will, which was amazing for me, but may not have been the same situation for everybody,” Zhukovsky said.

Monica Hannush ’16, who was reinstated in the fall of 2013, had a much more difficult experience in Pierson College, where she butted heads with college administrators.

“I had a very poor relationship with my dean,” Hannush said. “We had a new [head] in Pierson at the time, but I was trying to stay maximally off his radar. The last thing I would have done was make a meeting with him.”

Holloway told the News that students who prefer not to approach administrators in their residential colleges can reach out to other advisors at the University, such as coaches, chaplains and cultural center directors.

“There’s no doubt there’s variation [among deans], because we aren’t robots,” Holloway said. “For students who really did have a difficult time with their dean, it’s important to remember that they have other resources. It’s not that it’s easy for an individual who’s not having a positive experience with an adult on campus to go to another adult and say this isn’t working, but every student has options.”

None of the 12 residential college deans other than Parndigamage responded to emails or phone calls requesting comment for this story.

According to former Saybrook College Dean Paul McKinley — who now works as director of strategic communications for Yale College — college deans are highly attentive to the needs of reinstated students.

“There are people standing by 24/7 who are also paying attention 24/7 to how people are doing,” McKinley said. “There is a tremendous amount of outreach that is going on all the time. They are very mindful of people who have come back and work with them closely.”

Assistant Dean of Academic Affairs Pamela George — the chair of the committee that evaluates reinstatement applications — told the News that residential college deans help reinstated students plan their semesters, and refer them to other campus resources. She added that the deans receive “extremely thorough training.”

“It always takes some time for reinstated students to establish a personal connection if the dean is new, but because the deans live in and take their meals in the college, they have many opportunities to meet with reinstated students,” George said. “All deans, veteran or new, know exactly whom to call when a student needs help.”

Still, Williams said that upon returning to Yale, she did not receive institutional support beyond Branford College, where she had a strong relationship with her head of college and dean. She added that the University should offer reinstated students broader support and recognition.

“Even making you feel like they know that you exist and that you are a student again after they kicked you out and took you back, and that they are aware of this [would have been helpful],” Williams said. “They’re going to make a whole big fuss about sending you home, and then you come back and it’s like ‘Oh, did that happen?’ It would have been helpful to feel like somebody was thinking about it.”

(Ashna Gupta)

AFRAID TO ASK FOR HELP

The University announced reforms to the withdrawal and reinstatement process less than two years ago, in spring 2015. They included an extended timeline for leaves of absence, policies designed to alleviate the financial burden on withdrawn students and the replacement of the term “readmission” with “reinstatement.”

But they did not directly address one of the central reasons that Wang — who had withdrawn earlier in her college career and committed suicide in January 2015 — was unwilling to use Yale’s mental health resources: a rule in Yale’s academic handbook allowing the director of MH&C to recommend students for withdrawal against their will.

“She was routinely lying to her therapist,” a friend of Wang’s told the News in January 2015. “It was very common for her to express suicidal ideations and then she immediately followed that up, explaining that if we reported her she would be kicked out of Yale and have no reason left not to kill herself.”

Nearly two years later, that concern seems to have endured, especially among students who have experienced Yale’s reinstatement system firsthand.

Five of the nine students interviewed said they have avoided interacting with MH&C for fear of being forced to withdraw. One student — who was reinstated in the fall of 2015 and asked to remain anonymous — said she instinctively “self-censor[s]” around anyone affiliated with the University.

Hannush said she initially got along with her clinician at MH&C, but later regretted sharing information that administrators ultimately used to force her to withdraw. Although Hannush recognized that the counselors at MH&C were trying to help her, she said the experience left her feeling “betrayed by the system.”

In February 2013, Williams’ freshman counselor — an important resource for her before her withdrawal — took her to Yale Health for treatment for self-inflicted cuts. The doctor called in clinicians from MH&C, and soon an ambulance was transporting Williams to a psychiatric ward at Yale New Haven Hospital. Shortly after, Williams was forced to withdraw in what she described as a “Salem witch trial situation.”

“That’s when I learned. I had been completely honest with my therapist at home, who I had been working with for two and a half years, because that’s how you make progress,” Williams said. “I was completely honest with her, so that’s what I thought you were supposed to do. You’re supposed to be honest. Nope. I would never go to Yale MH&C now and tell them anything.”

Yale College’s Academic Regulations state that the Yale College dean can require a student to withdraw if MH&C advises that the student “is a danger to self or others because of a serious medical problem or that the student has refused to cooperate with efforts deemed necessary by Yale Health to determine if the student is such a danger.”

According to Holloway, individual clinicians can report concerns about a student to MH&C Director Lorraine Siggins, who typically meets with the clinician or interviews the student before deciding whether to recommend a required withdrawal. Students’ conversations with MH&C clinicians are not shared with the deans of the residential colleges.

“It’s based on the clinician’s interpretation of the exchange that’s happening with the student, and all the information that the clinician has with the student,” Holloway said. “It’s not about a stray word, or some phrase that’s taken out of context.”

Siggins did not respond to multiple requests for comment. However, Holloway defended Yale’s withdrawal policy, saying that the University always has students’ best interests at heart.

“Our main thing is that we want students to be healthy,” he said. “It is not about reputation, it’s about students’ health and well-being. The best place people get healthy is to be at home or some facility close to home which can tend to their needs. For students who are struggling with these issues, we never want to kick them out. We want them to get healthy, we want them to come back.”

Alexa Little ’16, who was reinstated in fall 2014, said she recognizes that the policy is designed to keep Yale students safe. But despite those good intentions, she said, the University’s power over personal health decisions creates a “surrealist landscape” in which students are not given the benefit of the doubt “when it comes to handling their own health.”

One student currently working toward reinstatement — who requested anonymity for privacy reasons — said Yale’s withdrawal policy discourages students from reporting suicidal thoughts.

“This is an issue that administration and people who have been around the Yale scene for a while have known about,” the student said. “This has basically been a hush-hush, don’t ask, don’t tell situation for a long time.”

Last spring, the student reported suicidal thoughts to MH&C officials and admitted himself to the psychiatric ward at Yale New Haven Hospital. After a few days at Yale New Haven, the student believed he was well enough to remain at the University — but he was overruled by his doctors, who insisted that he leave campus.

“Yale does not care about a student’s well-being,” the student said. “The reality is, Yale does not care about the welfare of the students. Yale cares about whether or not there is a tragedy that occurs on their doorstep and whether or not they get the publicity for it.”

NEXT STEPS

A Yale College Council report on withdrawal policies helped drive the University’s reforms in 2015. Now, nearly two years later, the YCC is planning to make withdrawal and reinstatement a focus of its advocacy work once again.

In an interview with the News, YCC President Peter Huang ’18 said that this year the YCC will likely explore the support mechanisms available to students after reinstatement. In 2015, he explained, the YCC proposed a peer mentoring system — similar to the cultural centers’ peer liaison program — that would match recently reinstated students with older advisors who have been through the process. The proposal was not incorporated into the 2015 reforms, but Huang said the YCC may push to see it introduced in the near future.

“[Reinstated students] definitely feel a disconnect from the community,” Huang said. “I think that’s something that we need to look through again. We’re just trying to look into different avenues so that we include support. Especially for an issue as nuanced as this, there can never be enough support.”

Indeed, Hannush and Zhukovsky suggested initiatives similar to the peer liaison proposal. They said that they would have benefitted — both before and after their reinstatement — from the advice of someone who had been reinstated.

“It’s not the going at it alone that’s as hard as the idea that you are going at it alone when you’re not,” Zhukovsky said. “We’re in a place with a lot of people, a lot of resources. There’s got to be at least one person for everybody that can help support.”

George said she holds periodic lunch meetings with reinstated students to help them transition back to Yale. The lunches are not mandatory, but they allow students to stay in touch with George and ask questions about their return to campus.

“We are continuing to manage the implementation of this still newish system, which I do think is an improvement on the past,” Holloway said. “We’ll keep our eyes on it to see how we’re doing. This is a process that we’ll know a lot more about in a year’s time when we’ve had more cohorts come back.”

But Hannush, who did not get along with her college dean, said the University should still do more to support students reinstated for mental health reasons.

In her view, the University should not only make it clearer to students what resources are available upon their return; it should also allow students to more easily transfer out of colleges if they feel uncomfortable, even during the course of the school year or right before the start of classes in August.

According to Williams, the University must introduce a greater degree of choice into its withdrawal policy, given that once students return to campus they are often afraid of being forced to leave again by MH&C.

Regardless of potential changes, some students who have gone through the reinstatement process said they may never look at Yale in the same way.

“It’s tough to have had such love for a place and go through that difficult experience and come back fundamentally changed,” Little said. “No one was happier to go to Yale than I was, and now I have a very difficult relationship with Yale because I went through this process.”