David Hurtado

Months after June 23, when New Haven declared a state of emergency after a tainted batch of heroin led to a surge in opioid overdoses, local officials are still considering how to combat the city’s ongoing opioid issue.

In the wake of the June incident, which resulted in nearly 20 overdoses and three deaths, City Hall proposed equipping New Haven Police Department officers with the opiate anti-overdose drug naxolone — also known by its brand name Narcan. The idea, however, was met with resistance from the police and fire unions: Currently, firefighters are the first responders to medical 911 calls, and are equipped with and trained to administer Narcan, said Rick Fontana, the deputy director of emergency management.

New Haven’s Narcan supply dropped significantly after the June incident, but Fontana said that within days, the state replenished its supply of the drug at no cost, distributing roughly 700 units of Narcan throughout the city.

But no definite solutions are yet in place for New Haven to make significant headway in its fight against opioid use.

“[Harp’s] hope is that as many people as possible would have access to the antidote and be trained in its use,” city spokesman Laurence Grotheer said. “There’s no question that on [June 23], lives were saved due to the administration of Narcan.”

According to Grotheer, the progress of Harp’s proposal to equip police officers with Narcan has become a matter of negotiations with the police union.

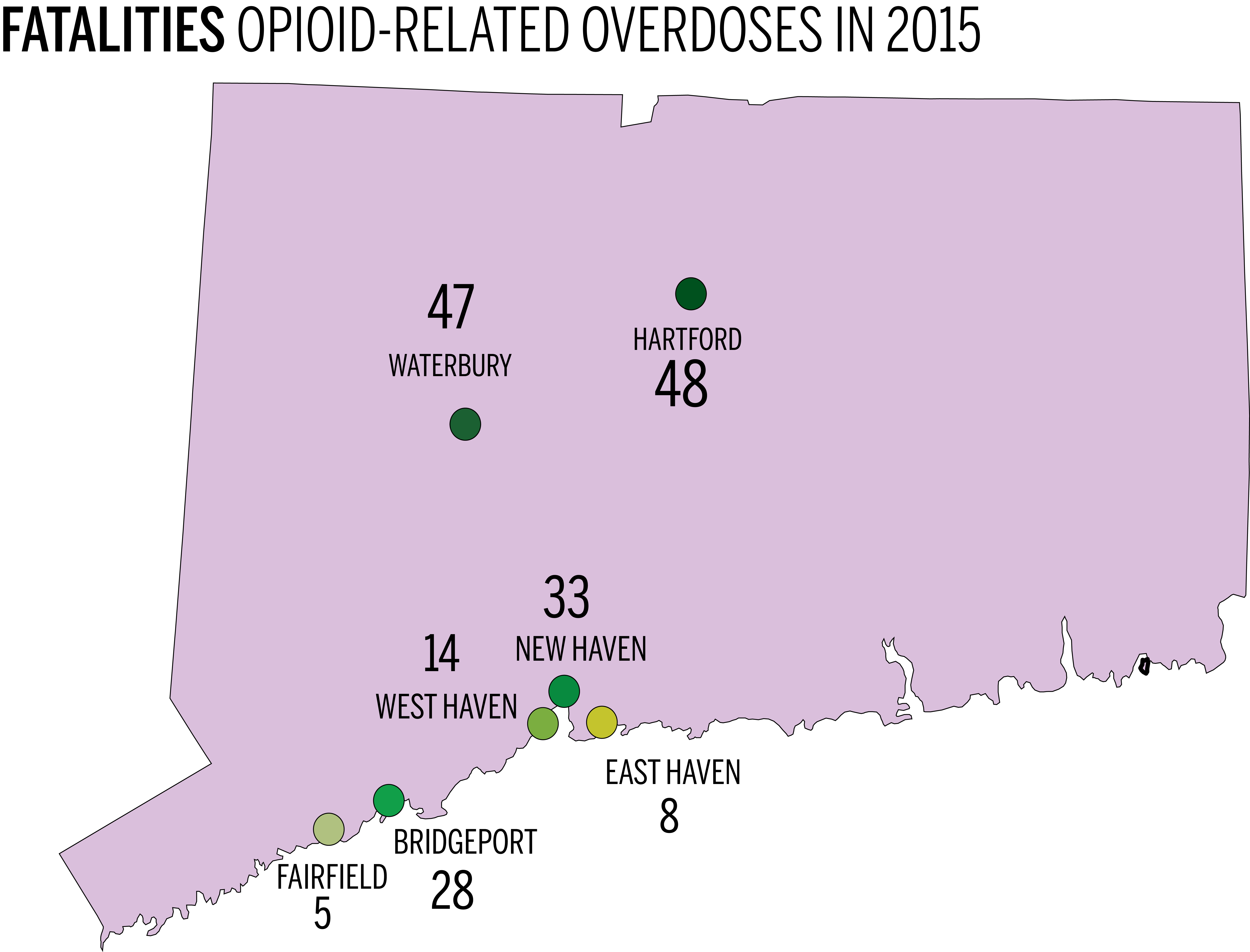

Fontana said that addressing the opioid epidemic remains one of Harp’s top priorities. He added that New Haven has one of the highest rates of drug overdoses in the state and estimated that firefighters and paramedics administer Narcan an average of five times per week in the city. Some incidents require multiple doses to revive the overdose victim, he said.

However, Fontana added that recent turnover in many of the city’s top leadership positions has slowed progress in the fight against citywide opioid use.

“We’ve had pretty big leadership changes, so at this point we’re still in the process of evaluating how to address it,” Fontana said. “When leadership changes, it becomes an obstacle in getting it done as quickly as you like. Plans for new initiatives get sidetracked.”

The NHPD, for example, has been without a permanent police chief for 14 weeks, since former Police Chief Dean Esserman went on leave and later stepped down from his position because of poor job performance. And the New Haven Fire Department just recently appointed its new fire chief, John Alston. The department has had several interim chiefs since former Fire Chief Allyn Wright retired in January.

As for combating opioid use with Narcan, Fontana said there are three main options to consider, including outfitting all police officers with Narcan and training them in its administration.

Another proposal is to launch a pilot program in high-risk areas like Downtown New Haven and Fair Haven to determine whether equipping officers with Narcan would be effective. And an additional option is to put Narcan kits in each police patrol car and train all police officers in its administration, a measure that would save the cost of outfitting roughly 400 law enforcement officials with $100 Narcan holsters.

The city is also looking to partner with pharmacies and outreach services to confront opioid use, Fontana said.

According to Fontana, the main considerations for these proposals are cost, effectiveness, collective bargaining and training for a department as large as the NHPD.

Yet progress is on the horizon. Fontana noted that the city has been collecting data on each Narcan administration episode, which will inform future initiatives, and has implemented a universal referral form to help those with drug addictions quickly receive help.

Additionally, following the June overdoses, the Connecticut State Department of Public Health said New Haven would receive $30,000 grants in each of the next three years to bolster efforts to combat the opioid crisis. Five other cities received the same grant on July 11.

Grotheer said the Harp administration hopes to see a broad-based approach to the city’s opioid epidemic, which might include training homeless shelter workers and health department personnel in administrating Narcan. The city is committed to identifying the sources of illegal drugs and restricting the use of fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that is used to increase heroin’s potency, Grotheer said.

NHPD spokesman David Hartman said the proposal to equip officers with Narcan was “only an idea, and not a bad one.” Yet he emphasized that the proposal is a consideration of the city government and that police officers are not the first responders to medical emergencies like overdoses.

However, Hartman added that the illegal sale of opioids is a police matter, and that the NHPD has been partnering with the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration to combat the problem.

“Now, when we get calls for overdoses, we try to collect evidence, even if we’re not going to make an arrest,” Hartman said. “We’re building with the DEA a local database of drugs and their origins.”

However, he added that the citywide and statewide conversations that emerged from this summer’s overdoses were crucial for the NHPD in understanding the pervasiveness of the city’s opioid issue.

“What has evolved from these incidents and the national spike in overdoses is a wider dialogue about the issue,” Hartman said. “It was eye-opening for us to see how many overdoses there are in New Haven, because we are not called to them.”