On November 9th, the morning after Election Day, a sizeable number of people in this country are going to wake up knowing that they cast a ballot for the losing presidential candidate. In all likelihood, they are going to be angry, disappointed and scared by the prospect of living for the next four years with a government led by a candidate they did not support. From that moment to the end of his or her term, the next president will need to find a way to include them in a political system that advances their political, economic and social interests.

Today, with little more than a month until Election Day, public discussion remains focused on the existential threat that one candidate (or the other) allegedly poses to principles shared by all Americans, regardless of political creed. Unsurprisingly, both campaigns now seem to be more willing than ever to achieve victory no matter the political cost. Some supporters even admit that they think the stakes are too high in this election to be caught up in the methods by which it is won. But what happens when fear of the present replaces hope for the future?

We seem to reject our awareness of the fact that we too might end up as one of the people counted in that sizeable number. And we might feel, as undoubtedly such people will, that the rest of the world, “Just doesn’t get it.” We probably will be angry at those who “blew it.” We might be disappointed that fellow supporters “didn’t see it coming.” And we are likely to be scared by the uncertainty of “that man” or “that woman” leading the next administration.

Instead, we like to embrace the idea that we are in the majority. We want to wake in a celebratory mood, knowing that we supported the candidate we found best prepared to take our country in a new direction. Of course, one would be justified in that moment to appreciate the satisfaction of having one’s opinions and beliefs validated by other voters: “To the victors go the spoils.” However, one would demonstrate considerable foresight and compassion by turning toward those who have not experienced such a feeling.

Similarly, one who ends up on the losing side should not shun efforts at reconciliation. One might hold the minority’s ability to frustrate legislative and executive affairs, but one’s interests probably will be better served seeking out efforts where compromise is possible. One might feel that the winning side demands too much, but if compromise is the essence of our American democracy, than the fundamental idea that makes our republican government possible is acceptance of the fact that one can compromise on a policy without necessarily compromising one’s principles.

The second presidential debate on Sunday night thus offers an opportunity. Listening to each of the candidates talk, we can attempt to transcend the rhetoric of the moment and empathize with other voters, especially those with opinions starkly different from our own. This does not mean that we cannot focus on the important issues that continue to divide our society, but that we should look for those areas where we can make common cause.

Taylor Drew Holshouser is a junior in Saybrook College. Contact him at taylor.holhouser@yale.edu .

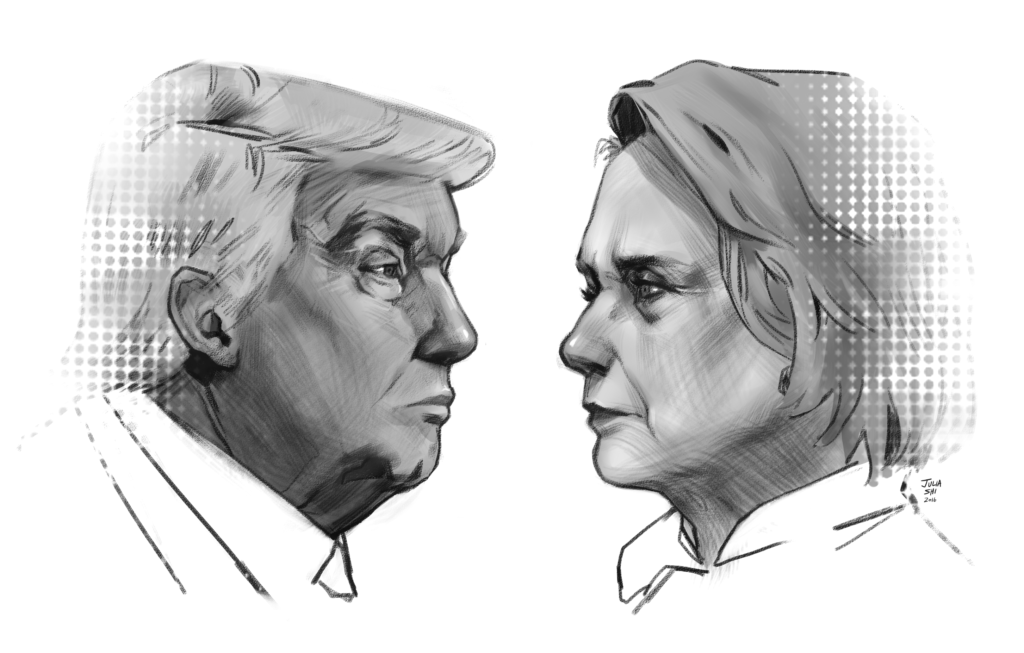

Illustration by Julia Shi.