Over the last few years, with cases of sexual misconduct on college campuses garnering widespread media attention, various groups from across the political spectrum have weighed in on what effective Title IX enforcement should look like and whether colleges are equipped to enforce it. Last month, the Association of American University Professors added to that conversation with a new draft report, which raised concerns about how schools’ applications of Title IX may be jeopardizing faculty freedom and actually hampering efforts at gender equity.

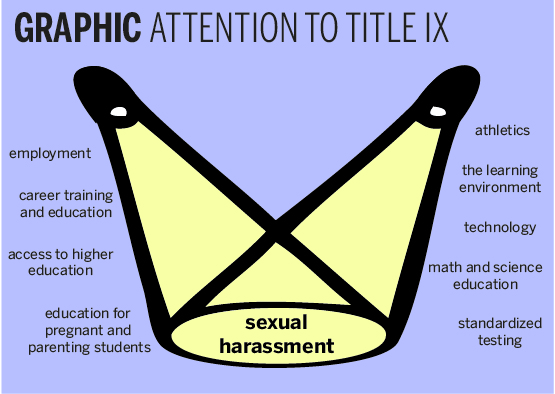

Title IX — a federal statute among the Education Amendments passed in 1972 — protects individuals from sex discrimination in all educational programs and activities that receive federal financial assistance. But as universities have recently used the statute to crack down on sexual misconduct, faculty rights to academic freedom, including free speech, due process and shared governance, have been upended “in unprecedented ways,” the report argued. In particular, it pointed to attempts to censor faculty expression in the name of preventing harassment. In addition, an overemphasis on Title IX’s provisions regarding sexual harassment and assault has led the federal Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights and university administrations to neglect other components of Title IX protection, the report said, such as equal access to athletics, career training, technology and math and science education.

Yale itself has recently grappled with questions of proper sexual misconduct adjudication, as well as of faculty free speech, but not in conjunction with each other. Both authors of the AAUP report and Yale professors interviewed agreed that the concerns raised in the report, while relevant, do not seem to be pressing issues on Yale’s campus. The draft report is open to comments from AAUP members until April 15 and will be published later this spring.

Although members of the AAUP drafting committee said they are not familiar with the specific circumstances at Yale, they agreed that shared governance between faculty, staff and administrators should strike a balance between effective policies against sexual harassment and overreaching ones that infringe upon academic freedom and disregard other aspects of gender equity.

“Overly broad definitions of ‘hostile environment sexual harassment’ have intruded on academic freedom in teaching, research and public speech,” said Risa Lieberwitz, a professor of labor and employment law at Cornell University’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations who chaired the drafting subcommittee. “[These definitions] have been used by the Office for Civil Rights of the Department of Education, which enforces Title IX, and by some university administrations in taking punitive measures against faculty members.”

The report listed cases in which faculty members were accused of sexual harassment when they included sexually explicit materials in their curriculum. In some cases, the professor was dismissed by the university. Not only was due process denied to faculty members on several campuses, the report said, but they were also “largely excluded” from participating in shared university governance and determining how and whether sex should be discussed, taught and researched.

According to Anne Runyan, an ex-officio member of the AAUP drafting subcommittee and a professor of political science and women’s, gender and sexuality studies at the University of Cincinnati, WGSS is an under-resourced department in many universities. If research and teaching on gender, sexuality, gender and sex discrimination are further curtailed because they may be “uncomfortable” topics for students, Runyan said, the field’s situation would only worsen.

Runyan added that the OCR’s 2011 guidelines, which state that Title IX should not be interpreted in ways that interfere with academic freedom, seem to have been lost in many universities’ Title IX procedures. According to the guidelines, speech and expressions that are perceived as offensive by some students are not legally sufficient to constitute a sexually hostile environment under Title IX; instead, the harassment must be serious enough to limit or deny students’ participation in their education program. But when this caveat is overlooked, Runyan said, there is no longer “a robust and critical educational environment.”

The report also highlighted the “preponderance of the evidence” standard that universities use to adjudicate cases of alleged misconduct, which only requires more than 50 percent certainty that the offense occurred. This is a lower standard than is used in criminal courts, and Lieberwitz argued that the OCR’s 2011 decision to replace the “clear and convincing evidence” standard with this new standard curtails faculty members’ rights to due process when they are accused of misconduct.

But Dean of the CUNY School of Law and visiting professor at the Yale Law School Michelle Anderson LAW ’94 defended the preponderance standard, noting that most college campuses that have identified a standard of proof for their disciplinary proceedings have used the preponderance standard for years. It is therefore incorrect to say that the “clear and convincing” standard was the “prevailing” standard before the OCR clarified the issue in 2011, Anderson said.

Professors on Yale’s campus said faculty rights and meaningful enforcement of Title IX are not mutually exclusive. They emphasized the role faculty have played, and continue to play, in shaping Yale’s enforcement policies. Yale’s University-Wide Committee on Sexual Misconduct — which hears all formal complaints of sexual misconduct — was formed in July 2011 as a faculty-driven initiative, a few months after students filed a Title IX lawsuit against the University. Last semester, UWC procedures were modified based on recommendations from a faculty committee led by Yale Law School professor Kate Stith. David Post, chair of the UWC and professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, also told the News that the chair position “has been, is currently and will continue to be a senior faculty member.” Roughly half of the UWC’s members are professors.

“I do not know enough about Yale to comment specifically, but it does appear … that the faculty-driven and populated [UWC] comports with the kind of faculty input AAUP is recommending as long as faculty also had input in how sexual misconduct policies were formed, not just the adjudication of them,” Runyan said.

History Director of Undergraduate Studies Beverly Gage ’94, who chairs the Faculty of Arts and Sciences Senate — a body intended to serve as a voice for faculty concerns — did not return a request for comment.

The AAUP report also noted that the narrowed emphasis of Title IX on sexual misconduct has diverted attention and resources away from other crucial components of gender equity.

“While the original aims of Title IX and the legal meaning of ‘sex discrimination’ encompass more than sexual violations, today the claims most readily associated with Title IX involve sexual violence or sexual harassment, whether actual conduct or speech,” the report continued. “Further, the singular focus on sexual harassment has overshadowed issues of unequal pay, access and representation throughout the university system.”

Runyan said students deserve “kudos” for highlighting the pervasiveness of sexual misconduct on college campuses and applauded their efforts to demand administrative attention and response. But she emphasized that other areas of sex and gender discrimination are not solved, and female faculty could be hurt, not helped, by Title IX.

Professors on Yale’s campus affirmed the University’s commitment to effective Title IX enforcement, including but not limited to addressing sexual misconduct.

“Faculty members are strong and active participants within the UWC, and faculty from across the University have a long history of active engagement in addressing sexual misconduct and other issues related to Title IX, such as gender equity,” Post told the News.

Other faculty members serving on the UWC directed all requests for comment to Post.

University Title IX Coordinator and Deputy Provost Stephanie Spangler emphasized that it is important to take all forms of gender discrimination — which is the overarching focus of Title IX — seriously.

Associate Dean for Academic Affairs at the CUNY School of Law and visiting professor at the Yale Law School Julie Goldscheid said addressing sexual misconduct on college campuses ultimately calls for a balance of different factors.

“Universities’ obligations to respond to sexual assault on campus require a nuanced response that requires careful balancing of a range of factors,” Goldscheid said. “OCR investigations are administrative responses to claims of discrimination and are not criminal proceedings. The overall goal of advancing equality should figure prominently in all responses.”

Correction, Apr. 4: A previous version of this article misstated that most campuses have used the “preponderance of the evidence” standard in their disciplinary processes for years. In fact, many campuses have not articulated a clear standard, but the colleges that have identified a standard of proof have used the preponderance standard for years.