A few dozen students sit in a lecture hall at the Yale Law School on a Tuesday afternoon. They are dressed casually, their backpacks bedecked with orange felt squares bearing the letter “Y.” Their furrowed brows mask a mild excitement, and they whisper amongst themselves across the rows of desks. It’s two weeks into the second week of their spring semester, and the undergraduates of Fossil Free Yale are full of energy.

And it is energy that brings them here. Part of Yale’s $25.6 billion endowment is invested in the fossil fuel industry, and for the past four years, students in FFY have been calling for divestment. Polluted seas, smoky skies, rising tides — FFY argues that Yale has a moral obligation to pull investments from the industry held largely responsible for destroying the planet and changing the climate.

A line of students in the center row of the hall raise six orange posters, one letter per student: “D-I-V-E-S-T.” Silence falls as members of Yale’s Advisory Committee on Investor Responsibility (ACIR) file into the hall.

Yale Law professor and chair of the ACIR Jonathan Macey stands to speak. Yale University is a not-for-profit organization, he says, and its governing body is the Yale Corporation. Macey describes the ACIR — composed of two members of the faculty, two staff members, two alumni and two students — as “a kind of conduit … between the Yale community and the [Corporation].”

Macey exhibits a mixture of neutrality and caution while discussing Yale’s investments. FFY sits silently and waits for him to finish: his message is familiar, and they have heard it before.

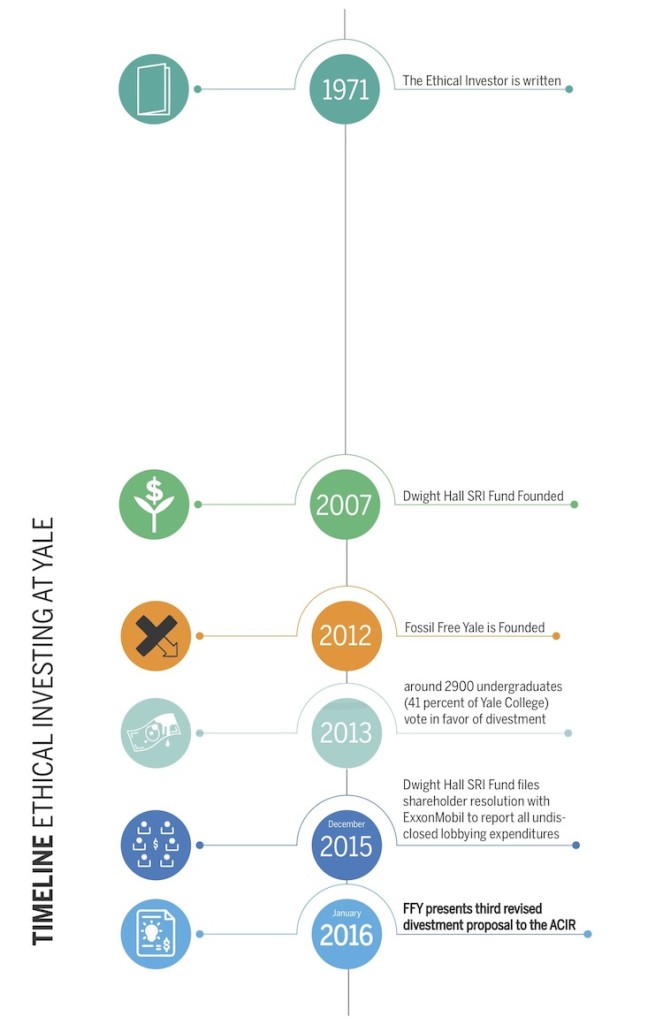

When Macey ends his speech, FFY Communications Director Chelsea Watson ’17 steps to the stage to present FFY’s third revised divestment proposal. “We are serious, yet Yale does not take us seriously,” she says. “We have given you our all, and we now leave it up to you, the ACIR, to decide what you will do with it.”

Fossil Free Yale has been the public face of divestment on campus for the past four years. Mobilizing undergraduates, the group has fought, without success, for Yale to remove its investments from the fossil fuel industry.

Recently, though, another group has started advocating for divestment.

Behind the front-and-center FFY crowd sit four members of the Dwight Hall Socially Responsible Investment Fund, an undergraduate group founded in 2007 with 20 members, a $100,000 endowment and an entirely different approach.

They watch Watson’s speech from the back row, all wearing suits.

—

Like so many battles in human history, the divestment debate at Yale centers on a book. The Ethical Investor — a 150-page text written in 1971 by a Yale Law School professor and a Yale theology professor — has guided the University’s investment decisions for over four decades. Every tricky moral question about Yale’s endowment in the past 40 years has been addressed, in some way or another, by consulting the book.

University Provost Benjamin Polak has described The Ethical Investor as a “touchstone” for Yale’s investment policies, a “simple and transparent” standard to keep the endowment in line with the University’s mission. Since it was published, Yale has divested from companies in apartheid South Africa and oil companies in Sudan in accordance with the book. The Yale Corporation Committee on Investor Responsibility (CCIR), which takes advice from the ACIR, said in a 2014 statement that those divestment choices were based “on a well-identified set of injurious actors,” companies which were assisting oppressive regimes that violated international human rights and freedoms.

The CCIR has already contended that climate change and oppressive regimes are vastly different problems.

In their 2014 statement, the CCIR said that The Ethical Investor’s premise is that Yale’s endowment should prioritize the University’s teaching and scholarly work over non-economic ethical issues. And one of the book’s authors, Jon Gunnemann GRD ’75, agreed in a Yale Daily News article last year, saying the endowment should support the educational goals of the University and “not be used as a social weapon.”

“The solution to [climate change] cannot be identified with a specific set of companies or even companies alone,” the CCIR wrote in 2014. “Sensible and sound governmental policies are essential to reduce the threat of climate change.”

Instead of appealing to ethics, though, the new Dwight Hall SRI Fund is using a specific passage in the book to push for divestment.

The passage reads: “The university will not exercise its shareholder rights, but will instead sell the securities in question, if a finding is made that: it is unlikely that, within a reasonable period of time, the exercise of shareholder rights by the university will succeed in modifying the company’s activities sufficiently to eliminate at least that aspect of social injury which is grave in character.”

In plain language, this means that if the University cannot get a company to improve by engaging with that company — a right that Yale has as a shareholder — Yale must divest from that company.

Could Yale be trapped by its own rules, forced by its own book to divest from fossil fuels? If Yale plays by the book, divestment from fossil fuels could become a real possibility in the near future.

—

After Watson finishes presenting Fossil Free Yale’s case to the ACIR, the FFY members rise en masse and march from the room. Only the ACIR, the four members of the SRI Fund and a few nonaffiliated students remain.

A calmer tone sweeps the space. The ACIR members, who had sat solemnly during the FFY presentation, turn in their seats and begin chatting. A certain professional friendliness comes over the audience, and the SRI Fund takes the stage.

In 2014, the SRI Fund purchased around $2,000 of ExxonMobil stock. And in December 2015 they filed — alongside other shareholders, including a Swedish pension fund and United Steelworkers — the first shareholder resolution by a student-led fund in the country.

The resolution asks ExxonMobil, the largest oil and gas company in the nation, to report all of its undisclosed lobbying expenditures. ExxonMobil’s expenditures have come under scrutiny after investigative reporting from major news organizations revealed that the company has funded groups like the American Petroleum Institute and the National Association of Manufacturers, which have helped obstruct evidence of climate change. Climate activists have also called out ExxonMobil for lobbying against scientific research in order to downplay the threat of global warming.

A shareholder resolution is a request made by investors in a company to vote on the direction of that company. The resolution is only the first step in a long process that usually, in the case of large companies like ExxonMobil, never comes to a vote. The company can table the resolution, and if it ever does come to a vote, it rarely gets majority support from other shareholders.

This is precisely how the SRI Fund hopes to corner Yale into divesting from fossil fuels: by showing that big companies like ExxonMobil do not listen to their shareholders. By filing a resolution that ExxonMobil is unlikely to green-light, the Fund could force Yale — another shareholder in ExxonMobil — to vote. And signs show that Yale would vote in favor of the SRI Fund’s resolution.

Macey said the ACIR is committed to voting in favor of resolutions that are consistent with the reality of climate change, citing this as reasoning for encouraging the ACIR to support the SRI Fund’s resolution. Such clear support contrasts starkly with the taciturn response the ACIR has given to FFY’s petitions in the past.

Russell Heller ’19, a member of the SRI Fund, said the plan could prove more effective than the direct-action approach favored by FFY. Heller said the SRI Fund prefers legislative methods and going through bureaucracy over making demands of the University.

“We’re taking a different route,” he said.

—

In FFY’s view, The Ethical Investor is an outdated guide with little to add to the present climate debate.

“The Ethical Investor is limited because it was written four-and-a-half decades ago,” Nathan Lobel ’17 told the ACIR at the Law School. In his presentation, Lobel said the book was an inadequate text, and would not help FFY convince the Corporation to divest.

Another FFY organizer, Elias Estabrook ’16, said the book needed an addendum because the scale of the climate change issue was almost incomprehensible for the authors who wrote it in the 1970s.

FFY argues that The Ethical Investor’s recommendations fall short in the face of the modern fossil fuel industry. They also believe the book downplays the efficacy of social movements and political action to create change. Given Yale’s prestige as an elite educational institution, FFY argues that divestment could signal to the global community a heightened awareness of the dangers of fossil fuels.

“By divesting, Yale would contribute to a consciousness shift within its community and beyond,” one FFY report reads.

For FFY, the lack of shareholder engagement in the fossil fuel industry is old news. Even though the group has not presented a test case like the SRI Fund’s, they have cited instances where large fossil fuel companies, including ExxonMobil, have not listened to their shareholders.

“Within the modern context, shareholder engagement has failed,” FFY member Griffin Walsh ’19 said.

Fossil fuel companies, FFY’s argument goes, cannot stay in business without extracting oil from the Earth. A fossil fuel company cannot, without destroying its business model, listen to shareholder or consumer calls for greener energy alternatives. And even if a shareholder resolution like the one proposed by the SRI Fund passes, no lobbying disclosure form could prevent ExxonMobil from staying in the oil and gas business.

“A fossil fuel company can’t leave reserves in the ground and remain in business,” Watson said at the ACIR meeting. “They are invested in the status quo. Shareholder resolutions will not work.”

—

Even as these student groups stand waist-deep in procedures and protests, the divestment debate is ultimately about the purpose of the University’s endowment.

The financial cost of divestment, some argue, could outweigh any social capital Yale might gain. As Yale seeks to continually grow its endowment, the Corporation may choose to ignore the moral culpability of fossil fuel investment. But can Yale strike a balance between fiscal prudence and ethical leadership?

School of Public Health professor Robert Dubrow, who attended the ACIR discussion, urged the committee to “take moral leadership and make a public recommendation in favor of divestment.”

While administrators have mostly given radio silence on the topic of divestment and fossil fuel companies, Yale’s Chief Investment Officer David Swensen recently recommended that Yale’s outside investment managers take climate change into account when investing Yale’s money. Swensen wrote that they should “assess the greenhouse gas footprint” of certain companies and try to make “investments with small greenhouse gas footprints.”

Speaking with the ACIR at the Law School, Dubrow asked why, if Yale is already attempting a kind of behind-the-scenes, gradual divestment, the University has not made any kind of public commitment to divest. He said divestment should be treated primarily as an ethical issue, not a financial one.

Some professors and students disagree, taking a purely economic view of the endowment.

A February 2015 study from economic consulting firm Compass Lexecon found a “highly likely and substantial” potential that divestment could decrease an endowment’s investment returns. No big oil, no big returns.

“The economic evidence demonstrates that fossil fuel divestment is a bad idea,” wrote lead author Daniel Fischel in the study. “These costs have real financial impacts on the returns generated by an investment portfolio, and therefore, real impacts on the ability of an educational institution to achieve its goals.”

Although lawyers, endowment specialists and economic professors agreed with the report’s findings, FFY members pushed back and said Compass Lexecon’s report was biased, since it was financed in part by a petroleum company. Furthermore, investing in oil and gas may not be as lucrative in the future as it has been, according to Brett Fleishman, senior analyst from the pro-divestment group 350.org. As oil prices plummet worldwide, companies in the U.S. oil industry like ExxonMobil have found their returns stagnant, signaling to some investors that oil profits may be on the decline.

“If you were an oil and gas exploration firm,” said William Jarvis ’77, director of the Commonfund Institute, an investment firm, “you’re close to out of business.”

—

FFY is at a crossroads now. In their view, the ACIR is an ineffectual organization, and the administration remains silent. The biggest issue they have, beyond climate change, is the University’s power structure. Estabrook said Yale moves at a snail’s pace, and thinks it impedes necessary and timely change.

In 2013, one year after the group’s formation, FFY was told to show how much student support it had through a referendum. Collaborating with the Yale College Council, FFY got 52 percent of the undergraduate student body to respond to questions about divestment. Of those who responded, 83 percent voted in support of divestment, which totals to around 43 percent of all undergraduates, or around 2,900 people.

In the spring following the referendum, several FFY members were given two hours’ notice to come to a meeting with the CCIR. They skipped class, hurriedly prepared an information packet, and made a presentation. But after the meeting, Yale gave FFY the cold shoulder.

“It was basically a slap in the face. We did everything we were told to do,” Watson said.

FFY did not turn the other cheek. Shifting their tactics, they began to stage protests and demonstrations, their megaphones pointed at Woodbridge Hall. When FFY members staged a sit-in inside President Salovey’s office, Yale Police wrote 19 students citations for trespassing and asked them to leave the building.

Yale pushed back on divestment in a way no University had before. With the sit-in, Yale became the first school to use police action against divestment protests. Harvard climate activists blockaded Harvard Yard for a week, Swarthmore students held a monthlong sit in; both protests were uninhibited by the schools’ administrations.

“It did hurt to be arrested by your University, rather than have a door open,” Estabrook said.

The sit-in was designed to force Yale to make a decision, to come face-to-face with FFY and give an answer. Watson said the sit-in answered a big question for FFY: If Yale finally listened to students, would it change its policies? The answer, Watson said, was a resounding no.

“They were listening and they didn’t care,” she said.

—

Although the University has kept silent on the topic of divestment, Yale may soon be forced to make a definitive decision. If the SRI Fund’s shareholder resolution is supported by Yale and then voted down, as SRI members expect it will be, the University will be presented with a dilemma. Can the University comply with its own rulebook while remaining invested in a company with a clear case of shareholder disengagement? Although the Dwight Hall group and FFY claim to be working independently, a victory for the SRI Fund would undoubtedly give ammunition to FFY against the University.

“If Yale votes its shares and then the measure fails, that … kind of proves [Yale] wrong and gives weight to the divestment argument,” Heller said. “[Yale is] going to have to revisit their entire ethical guidelines.”

The resolution was filed in December 2015, though first unveiled at the ACIR meeting on Jan. 26, 2016. Dwight Hall will meet in the coming months with ExxonMobil representatives. Heller said he expects ExxonMobil to table the resolution. Until then, the SRI Fund is standing firm, watching and waiting.

Macey is optimistic, not that the resolution will win a majority of shareholder votes, but that the mission of getting lobbying disclosures might succeed. Often, even shareholder resolutions that get fewer than 5 percent support are enacted voluntarily by the company a few years later. This is about getting marginal, incremental change in a company, he said.

“The fair measure of the success of one of these campaigns is whether they do it voluntarily,” Macey said.

—

Nearly a month after their meeting with the ACIR, on a chilly winter afternoon, FFY holds a “speak-out” on Beinecke Plaza. Forty-five students circle four suited, headless mannequins representing members of the Yale Corporation. Taking turns, the students share their frustrations with Yale’s unwillingness to change.

“We need to critically question if this power structure is a legitimate and appropriate governing structure for Yale,” says Alina Aksiyote ’16. “We shouldn’t be okay with the fact that Yale runs without student opinion.”

While the speeches focus largely on divestment, at times, they blur into more general condemnations of everything students see wrong with the University, from the name of Calhoun College to a lack of diversity among the faculty.

“We should have more of a say,” Aksiyote says. “The more we build with each other across grades, and really keep a presence here, that will be really powerful. I feel like things are really changing.”

Nobody uses a megaphone. Nobody is arrested. The speak-out lasts an hour, and then 45 undergraduates hug, pack up and walk away.