As tuition costs at the nation’s largest universities rise, Congress is pressuring schools like Yale to spend more from their large endowments on financial aid for low-income students. But University officials said the endowment is a complicated system and these proposals may be misguided.

Earlier this month, two congressional committees, the Senate Committee on Finance and the House Committee on Ways and Means, sent letters to 56 private colleges with endowments larger than $1 billion, including Yale, to inquire about how these universities manage and spend their endowments. In January, New York Republican Rep. Tom Reed drafted a bill that would require universities with endowments larger than $1 billion to spend 25 percent of their endowment returns on financial aid, with penalties for schools that do not comply. Yale currently spends around 5 percent of its $25.6 billion endowment on financial aid but does not calculate spending relative to its annual endowment returns.

These congressional efforts may misunderstand how university endowments work, according to University spokesman Tom Conroy. And the bill, if passed, could seriously disrupt Yale’s financial stability.

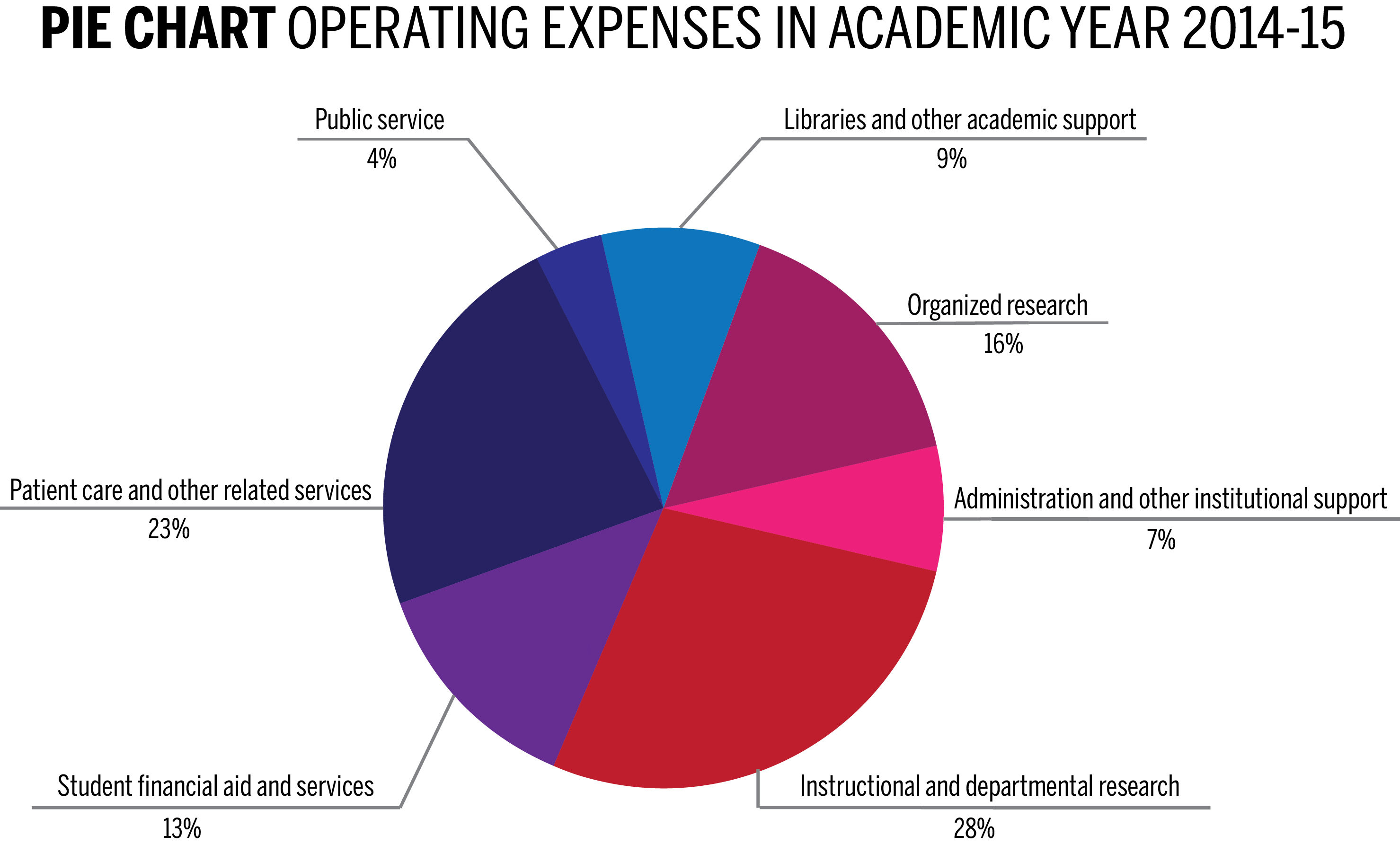

“Based on what we know about the bill, it is highly problematic,” Conroy said. “It sends the message that universities should spend less of the endowment revenue on research, on library and museum collections and on helping local communities. It could undermine Yale’s ability to meet its legal obligations to donors and could quickly diminish the endowment’s purchasing power.”

Yale’s Chief Financial Officer and Vice President for Finance Stephen Murphy ’87, who oversees the University budget, did not respond to requests for comment.

Conroy said Yale will respond to the Congressional request for information about endowment management and use before the April 1 deadline. The letter cites a National Association of College and University Business Officers’ report, which found that endowments over $1 billion had an average return of 15.5 percent. In the 2015 fiscal year, Yale saw an 11.5 percent return on its $25.6 billion endowment, which is still below the 15.5 average cited across other wealthy schools, though it is above many other Ivy League endowments.

The bill also does not take into account the “smoothing rule,” which is designed to keep University spending steady over a long period of time regardless of market fluctuations. The rule, which according to the 2014 Yale Endowment Report is “at the heart of financial discipline for an endowed institution,” keeps spending at a constant level from year to year, even when the endowment rises and falls dramatically. According to the endowment report, the smoothing rule makes sure Yale can spend money both on its current students and on future generations of students. Over the past decade the average spending rate from the endowment has been 5.1 percent.

But under Reed’s bill, universities’ annual spending would be tied to market performance, which could lead schools to spend excessively during times of financial prosperity and to cut spending during times of financial downturn.

While most nonprofit organizations are required by law to spend at least 5 percent of their earnings toward their missions, universities like Yale fall in a separate category of nonprofit and have greater flexibility with how much of their earnings they spend. Nonprofits are also tax exempt, which means the IRS cannot collect any of Yale’s earnings. These laws were put in place to encourage charitable enterprises like schools, but some in Congress think wealthier schools are not paying their fair share to students.

The letter, written by three Republican lawmakers, said that despite large investment returns, many schools continue to raise their tuitions. The committees, the letter said, are looking into “how colleges and universities are using endowment assets to fulfill their charitable and educational purposes.”

But Conroy said Yale is already using its endowment in a way that fulfills its educational and charitable obligations. Annual returns from Yale’s endowment fund much of Yale’s financial aid grants for low-income families, Conroy said, and the endowment also goes toward aiding New Haven students afford college and encouraging staff and faculty to buy homes in the Elm City.

“Everything that Yale does to improve the quality of life in New Haven … is ultimately made possible by the endowment,” Conroy said.

In addition, the endowment funds much of Yale’s educational undertakings as well. The overall financial aid budget for Yale is approximately $269 million a year. The endowment provides one-third of the annual University budget, while only 9 percent of the budget comes from student tuition and fees, Conroy said.

“Endowment spending is nearly twice the amount from a decade ago, and it provides funding for every school and department on campus,” Conroy added.

This is not the first effort from Congress to control university endowment spending. In January 2008, the Senate Committee on Finance asked 136 of the nation’s wealthiest schools to disclose information about endowment spending. The move came one year after schools like Yale and Harvard were seeing high investment returns of over 20 percent.

“Tuition has gone up, college presidents’ salaries have gone up and endowments continue to go up and up,” Republican Sen. Charles Grassley, who sat on the committee, said in a 2008 interview with The New York Times. “We need to start seeing tuition relief for families go up just as fast.”

But managing the endowment and budget is a complex balancing act, and congressional pressure has the potential to disrupt the balance, Conroy said.

“Yale does not believe that the balance it has been carefully achieving would be improved by statutes that mandate spending levels or limit the University’s choice in allocating resources,” Conroy said.