The leaders of two graduate student assemblies presented administrators with new data last week illustrating the financial struggles of graduate-student parents — the latest development in an ongoing campaign to secure child-care subsidies from the University.

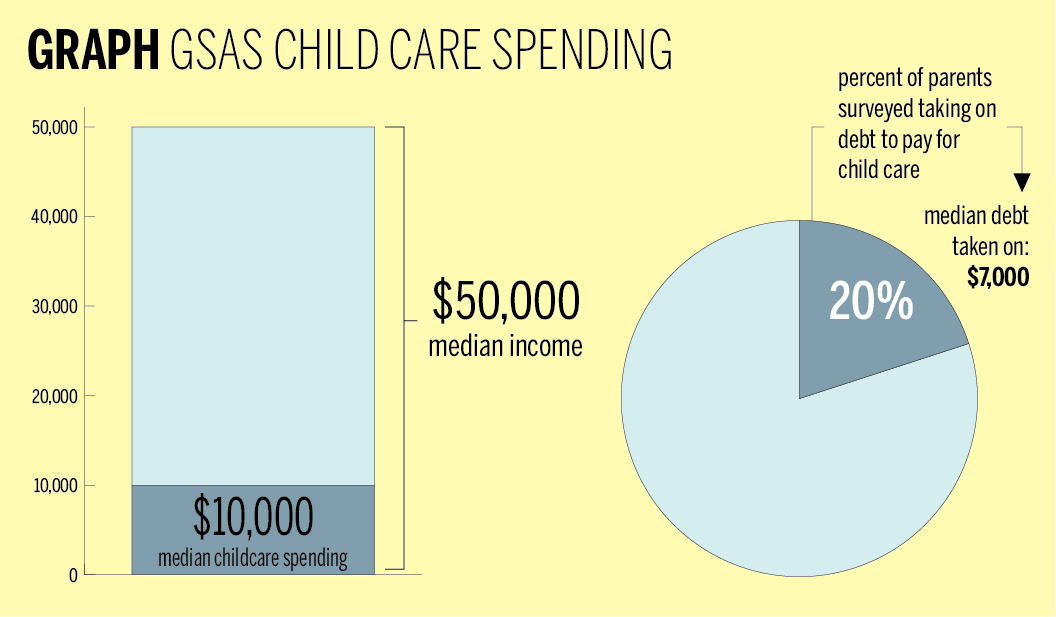

Elizabeth Mo GRD ’18, president of the Graduate and Professional Student Senate, and Elizabeth Salm GRD ’18, president of the Graduate Students Association, met with Graduate School of Arts and Science Dean Lynn Cooley last Thursday to advocate for financial support for graduate-student parents, who make up about 5 percent of the graduate and professional school population. Currently, the University does not provide any form of child-care funding for graduate- or professional-student parents, although it does offer free health care for students’ children. The data, compiled via a survey last semester, indicate that 20 percent of student parents in the Graduate School have taken on debt in order to pay for day care, at a median rate of $7,000 per year. On Tuesday, Cooley told the News that after months of discussions with the GSA she has made the child-care subsidy her “top fundraising priority,” and that the University must do more to support graduate-student parents.

“Providing greater child-care support is extremely important so that we can attract and retain the best students, especially women, in graduate school,” Cooley said.

The survey drew about 230 respondents, roughly two-thirds of the total number of student parents at Yale, although Mo said the data has not undergone thorough analysis and could be subject to change. The Facilities and Healthcare committee of the GSA also plans to release a separate report on the challenges faced by graduate-student parents before the end of the semester.

The campaign is focused primarily on the expenses associated with child care. Many graduate-student parents say the University, which does not currently collect data on the child-care spending of student parents, has an obligation to subsidize day-care costs. The seven Yale-affiliated but privately owned child-care centers on campus are among the most expensive in New Haven — the cheapest of the seven costs more than $1,300 per month — and offer only a limited number of spots.

The new GPSS data illustrates the substantial burden child-care costs impose on graduate-student parents. The median annual spending on child care for student parents in the graduate school is $10,000 — about 20 percent of the median income for families in that group. According to the GPSS survey, student parents in the professional schools spend even more on child care and tend to take on larger quantities of debt, but those additional costs are partly offset by their higher future earning potential.

The University does provide graduate-student parents with some services designed to ease the financial strain of raising children. It offers health insurance at no additional cost to the children of student parents enrolled on the Yale Health plan, as well as paid relief from academic work for eight weeks following a birth or adoption. Jeremy Jacox MED ’15 GRD ’15, a Graduate Student Life Fellow who specializes in assisting graduate-student families on campus and who is a student parent himself, said those offerings set Yale apart from many of its peer institutions.

But alongside Harvard and Dartmouth, Yale is one of just three Ivy League schools that does not provide child-care subsidies to graduate and professional students. If the University continues to neglect the child-care needs of graduate student parents, it risks stymying the progress of women in academia, Jacox said. At other peer institutions, child-care subsidies are often distributed on a need-based scale.

“Yale would be a beacon of progressive thinking on this issue by launching a development program to raise funds for a child-care facility on the main campus and an endowment to substantially reduce the cost of infant and toddler care on campus,” said biology professor Paula Kavathas, who serves as chair of the Women Faculty Forum, a gender equity group.

This is not the first time University administrators have taken up the issue of child-care support for graduate student parents. In 2005, then-University Provost Andrew Hamilton announced plans for an on-campus day-care center for the children of faculty and graduate and professional students, but the initiative fell through due to complications in zoning laws.

In 2006, the last time the GPSS gathered data on the financial burden of child care, 9 percent of graduate-student parents surveyed indicated that they had taken out loans in order to pay for day care, spending an average of $900 per month. 10 percent of respondents said they had considered leaving the University because it did not adequately support graduate students with children.

In recent years, the controversy over child-care support has grown even more fraught, as graduate students weigh the personal benefits of starting a family against the difficulties of navigating an increasingly competitive academic job market.

Anna Jurkevics GRD ’15, who has two children, said that when she announced her first pregnancy, she was greeted with “shock” from peers and advisors.

“Yale is a childless world,” she said. “I’ve had to fight to remind people to take me seriously.”

Jurkevics could not afford any of the on-campus day-care centers affiliated with the University, and she eventually enrolled her now two-year-old daughter in the Sunshine Preschool in Hamden, Connecticut, which costs $1,160 per month, nearly $200 less than the cheapest Yale-affiliated daycare. Nevertheless, for nearly two years, she and her husband could not afford a car and had to take turns biking their child to school, wrapping her in wool blankets on wintry mornings.

But the Thursday meeting appears to signal a new approach to these issues from administrators who some graduate-student parents say have previously ignored calls for child-care subsidies.

Last spring, Cooley held a “Dine with the Dean” luncheon to discuss the concerns of graduate-student parents, but only four student parents were able to attend, and the rest of the slots were filled by students in the economics department.

“We just got cut off,” said Jurkevics, who attended the lunch. “The rest of the lunch was about the econ students, how it was drafty in their building.”

At the lunch, Jurkevics added, she got the impression that Cooley did not understand the challenges of balancing child care with doctoral work, speculating that administrators from older generations are disconnected from the needs of modern graduate students.

“It sounded like it had never come across her desk that here are parents who are graduate students,” Jurkevics said. “It didn’t seem to be that she initially believed that it really was a problem.”

Cooley told the News that she “can only imagine that the student misunderstood something I said,” adding that she has been working with the GSA to formulate a subsidy plan since she was appointed dean in 2014.

Jacox said he attributes the lack of child-care subsidies at the University partly to the fact that no campus organization is dedicated specifically to lobbying administrators on behalf of graduate student parents.

“There isn’t very much parental representation on some of those committees, and maybe that’s why some of those issues haven’t come up historically, until more recently,” said Jacox, referring to the efforts of the GSA and GPSS.

But the push for child-care subsidies has gained momentum in recent months. On top of the GSA and GPSS initiatives, the Graduate Employees and Students Organization, the unofficial graduate student union, included child-care support in a list of demands it delivered to University administrators last May.

“Within the community, we all know that there is a population of parents,” Mo said. “We’re aware that it’s a struggle. And we’re trying now to be a voice for this group.”