Over 94 percent of women opt to remove their ovaries when undergoing a hysterectomy, a choice which might lead to negative health effects, according to Yale researchers at the School of Medicine.

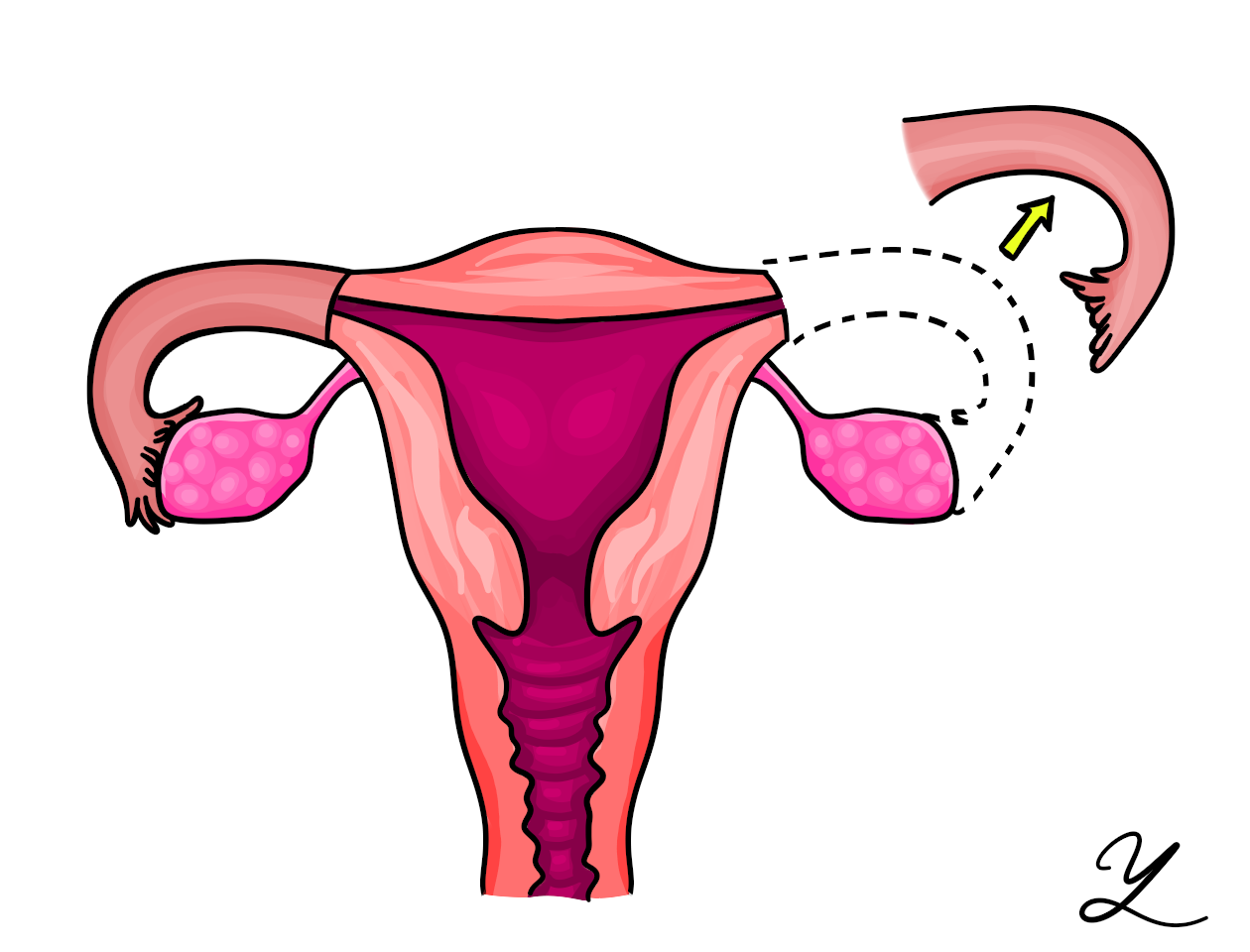

The new medical school study found that most women do not choose to conserve their ovaries when they have their uteri removed, even though studies have shown that ovary removal causes adverse health effects including bone, cardiovascular, cognitive and sexual health problems. Bilateral salpingectomy with ovarian conservation — removal of the fallopian tubes while retaining the ovaries — is an often-advised practice by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists in 2015.

Medical school professors and study co-authors Xiao Xu and Vrunda Desai studied the 2012 National Inpatient Sample for benign hysterectomies in adult women, which revealed that only 5.9 percent of women go through bilateral salpingectomy with ovarian conservation, leaving over 94 percent of women to remove their ovaries along with their fallopian tubes when undergoing the procedure.

“Keeping the ovaries is important,” Desai said. “Their removal can sometimes lead to … premenopause, or brain, heart and bone issues.”

The fallopian tubes are the major site where ovarian cancer develops, Desai explained. She added that the cancer exhibits few symptoms other than bloating and mild pain, making it hard to diagnose. Ovarian cancer is the eighth most common cancer, but it is the most deadly gynecological cancer, she said.

Desai said the researchers looked at 20,635 adult women who underwent hysterectomies for benign cases in 2012. She noted that the hospital rates of patients who underwent the bilateral salpingectomy procedure varied greatly, ranging from 0 percent to 72.2 percent of patients. Geographic region, patient volume served by a hospital and patient race were important factors in the likelihood that low-risk women would undergo bilateral salpingectomy and keep their ovaries, according to the study.

In describing the researchers’ challenges in conducting the study, Xu said their data was limited to inpatient hysterectomies, procedures that require postsurgical-recovery treatment in the hospital. But many outpatient hysterectomies, in which patients leave the hospital within 24 hours of surgery, also exist. Because their study examined cases from 2012, Xu underlined their future hope is to assess recent data for any differences.

“Our hope right now is to capture attention for providers and patients,” Xu said. “We want patients to be aware there are other options.”

Hugh Taylor, chief of OB-GYN at Yale-New Haven hospital, said Yale-New Haven has shifted, whenever possible, to leaving the ovaries within younger women who have a smaller risk of ovarian cancer.

“Yale’s been ahead of the curve,” Taylor said. “As the public becomes more educated, and the National Society guidelines change, I think more people will undergo [bilateral salpingectomies with ovarian conservation].”

At Yale New-Haven Hospital, there are stronger trends of younger women who prefer not to remove the ovaries at the suggestion of their doctors, especially those patients who are premenopausal, Taylor said. He added that anyone with less risk of cancer should keep their ovaries, as they regulate hormones and other health issues.

Lawson Tait introduced salpingectomies in 1883 as the treatment for ectopic pregnancy