Starting next fall, the “student summer income contribution” — summer earnings that students on financial aid are expected to contribute toward their tuition — for all upperclassmen will drop by $450, while that figure for students with “the highest financial need” will decrease by $1,350.

The changes were announced at a packed financial aid town hall meeting held Monday night in Linsly-Chittenden Hall. At the meeting, which was organized by the Yale College Council, Director of Financial Aid Caesar Storlazzi and Dean of Undergraduate Admissions Jeremiah Quinlan took turns explaining the policy reforms before hearing questions from students. Their announcement comes three weeks after a Nov. 17 email from University President Peter Salovey, in which he stated that the “student effort” would be reduced beginning in the 2016–17 academic year, among a series of other policy changes in response to recent campus movements. The student effort is a combination of the summer income contribution and a “student employment” expectation — earnings from a term-time job — that students are asked to put toward their term bill. Monday’s town hall was the first time since then that students have heard details about the reduced student effort, such as how large the reduction will be and whether the changes will affect the term-time expectation or the summer earnings requirement. Following the meeting, students interviewed welcomed the announcement as a first advance toward full financial aid reform, but emphasized that conversations about completely abolishing the expected contribution must continue.

“This is the first baby step … to making Yale accessible to all deserving students and all potential students,” said YCC President Joe English ’17, who has made financial aid policy a central issue of his time in office. “This conversation and this advocacy will not end — it will pick up tomorrow.”

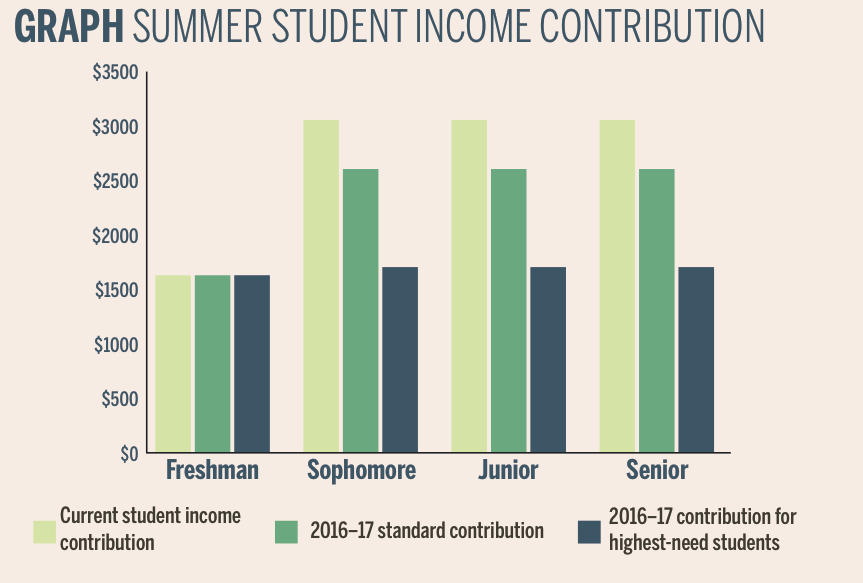

This academic year, the expected student effort is $4,475 for freshmen and $6,400 for sophomores, juniors and seniors. The student employment expectation, formerly known as the self-help amount, is currently set at $2,850 for freshmen and $3,350 for upperclassmen, while the student summer income contribution is $1,625 and $3,050 for freshmen and upperclassmen, respectively.

The student effort has been rising steadily over time, prompting widespread concerns among the student body about equity between students on financial aid and those from more wealthy families. Many on campus have decried the student effort, calling for its elimination to ensure that all Yale students can have the same Yale experience, which includes having time to pursue extracurricular activities and other interests. Since 2008, the student effort has increased by 17 percent when adjusted for inflation — nearly $1,000 in current U.S. dollars.

In January, the YCC published a report highlighting issues faced by financial aid recipients, such as a lack of transparency about aid policies and an inability to pursue unpaid summer opportunities. Since then, administrators in the Office of Undergraduate Admissions and Student Financial Services have been discussing reforms to the University’s aid policies, including possible changes to the student effort. Additionally, this summer, University Provost Ben Polak convened a committee to discuss Yale College’s financial aid policies. The committee consisted of high-ranking administrators such as Yale College Dean Jonathan Holloway, Deputy Provost Lloyd Suttle and Associate Vice President for Finance Steve Murphy. Polak then met with Salovey to present options for modifying the student effort before making a final decision.

In Salovey’s email, he specifically acknowledged the role that student activism has played in the reform process, making a direct allusion to the YCC report.

WHAT’S NEW

In total, the new changes will add $2 million to the University’s annual financial aid budget. At the meeting, Storlazzi emphasized that these funds are coming from additional administrative spending on financial aid and are drawn from the general budget of the University. Currently, Yale spends around $122 million per year on undergraduate financial aid. Quinlan said tuition for other students would not rise as a result of the reduced student effort for aid recipients.

At the outset of the meeting, Quinlan highlighted that the changes come in response to three issues he believes to be most troubling to students based on the YCC report and meetings with students both this year and last: the rise of the student effort, the jump in expected contribution between a student’s freshman and sophomore year and the need for heightened concern for Yale’s most financially needy students.

For the first time, the University has introduced a new category of students considered in the University’s financial aid policies: those with the “highest need.” Typically, Storlazzi said, these students have a parent contribution of zero, are eligible for Pell Grants if they are U.S. citizens, and come from families with no family assets, such as a home or family business. These students compose 10 percent of all students on financial aid, or around 300 students, according to Storlazzi. There are nearly 2,800 undergraduates who receive financial aid from the University.

Storlazzi added that students with the highest need should not be expected to contribute as much toward their expected student effort because they often have to send money back home, making it more difficult to meet the financial demands that Yale places on them.

The policy changes also address a sharp increase in the student summer income contribution between freshman and sophomore year. In the YCC’s January report, the committee wrote that many students matriculate to Yale with an incomplete understanding that this expected cost would rise during their time in college. Quinlan in the past has defended the disparity, noting that the required contribution is lower freshman year to allow students to ease into the expectation. While Quinlan maintained at the town hall that having this gap is “good policy,” he acknowledged that the changes have softened the transition.

The freshman-sophomore year jump has now been reduced to $1,475 from $1,925 for most students on financial aid, and to $575 for students with the highest need. Over four years, students with the highest need will pay a total of $4,050 less than they were previously expected to, while the remaining students on financial aid will pay $1,350 less.

Quinlan said the administration’s decision to focus the changes on the student summer income contribution as opposed to the student employment expectation is intended to allay summertime inequality, in which students on financial aid are often limited in which activities they can pursue because of Yale’s summer earnings expectation. He said students seem not to have as much trouble with the term-time cost, as data from the Yale Student Employment Office shows that students on financial aid who work on-campus jobs spend an average of less than five hours per week at those jobs.

Additionally, freshmen with the highest need will receive increased college start-up funds, which are used for extra expenses like winter clothes or room furnishings. This number has been increased from $800 to $2,000 for domestic students and from $1,000 to $2,000 for international students.

LUKEWARM AT BEST

Students at the town hall meeting were skeptical of the University’s changes. During the question and answer session, many students expressed disapproval of the changes as merely a half-measure, with several sharing emotionally charged stories of how the student effort has negatively impacted their Yale experience.

“We’re working like dogs and we’re not getting as much back as we deserve,” one student said to a round of applause. “We don’t want to keep a status quo of unfairness.”

“You’re supposed to bring leaders here to make the world a better place,” said another. “A lot of those leaders are low-income.”

Sara Harris ’19, who attended the event, said the measures are a step in the right direction, as long as they are the first steps and not the last.

Mikayla Rudolph ’19, another attendee, criticized Storlazzi and Quinlan for not being sensitive enough to students receiving aid, adding that the administrators do not seem to understand how difficult it is for students to navigate the process by themselves.

“There’s just a clear divide between the experiences low-income students have and the views that the directors of these departments have,” she said.

Another student questioned Storlazzi and Quinlan on their decision not to factor in varying levels of need, but instead divide students into just two categories: those receiving financial aid and those with highest need. The student suggested a sliding scale of reduction in student effort. Quinlan replied that he would consider alternative options for these classifications moving forward.

Though he is not officially involved with the decision, Dean of Student Life Burgwell Howard said he attended the meeting to hear student concerns that would inform his future work with undergraduates. He noted that he was interested in the students’ philosophy that while inequalities are a part of life, those should not exist at Yale as perpetuated by the student effort.

While Quinlan defended his view at the meeting that affordability should be the main consideration when administrators evaluate financial aid policy, students who attended generally felt that administrators should place more weight on ensuring that financial aid provides a common Yale experience for all students, regardless of wealth. When pressed to describe the Yale experience, Quinlan declined to do so, leading another student to interrupt him to say that the Admissions Office has already defined it in its marketing brochures.

Ultimately, Storlazzi said Student Financial Services will have to rely on others for input on what the Yale experience is and should be.

MOVING TO ZERO

Despite the reduction in the student summer income contribution, Tobias Holden ’17, who also attended the meeting, said both components of the student effort are still limiting. He also expressed that he would ultimately like to see the student summer income contribution completely eliminated. An aspiring medical student, Holden said applicants to medical schools are expected to do activities like research or working at a hospital during the summer, which is difficult for students who cannot afford to accept those positions unpaid.

He added that it is extremely difficult to find a paid research position during the year.

“The student income contribution is actually making it so that I’m not going to apply to professional school until I’ve had a year to work and save money outside of Yale,” Holden said.

English told the News that the YCC stands by its recommendation to eliminate the student summer income contribution entirely, articulated in the group’s January report. He took care to emphasize that while Monday night’s announcement was the culmination of many months of work, the YCC will continue to push for further financial aid policy reform. He said he is already scheduling meetings with administrators to discuss the topic further.

Storlazzi and Quinlan reiterated this notion, stating that there will be an annual review of whether the University is affordable for all students.

“Conversations about the financial aid program are ongoing,” Storlazzi said. “This isn’t the final decision. It doesn’t mean we’re never going to change this again.”

Still, prospects for a complete elimination of the student effort seem bleak at this point. Quinlan said the proposed reduction was the amount that made “financial sense” for Yale, given that the University has limited resources.

“Financial aid is a priority, but not the only priority,” he said, citing faculty diversity and enhancements to the library system as other important costs.

If Yale had unlimited resources, Storlazzi said, there would not be an expected student contribution. The claim is a philosophical shift from arguments in favor of the student effort by alumni and members of the Yale Corporation, who have maintained in the past that for a student to appreciate his or her Yale education, he or she must have “skin in the game,” according to English.

Holden dismissed the “skin in the game” idea as absurd.

“I think it’s ridiculous to imply that low-income students don’t already have a stake in their education,” he said.

Correction, Dec. 8: A previous version of this article misstated the administrators who met this summer to discuss Yale College’s financial aid policies. In fact, it was Deputy Provost Lloyd Suttle and Associate Vice President for Finance Steve Murphy, not Emily Bakemeier or Shauna King.