Friday marked the 17th anniversary of the still-unsolved murder of former Yale senior Suzanne Jovin ’99. Today investigators at the Chief State’s Attorney’s Office are still working to retest evidence and solicit potential witness accounts.

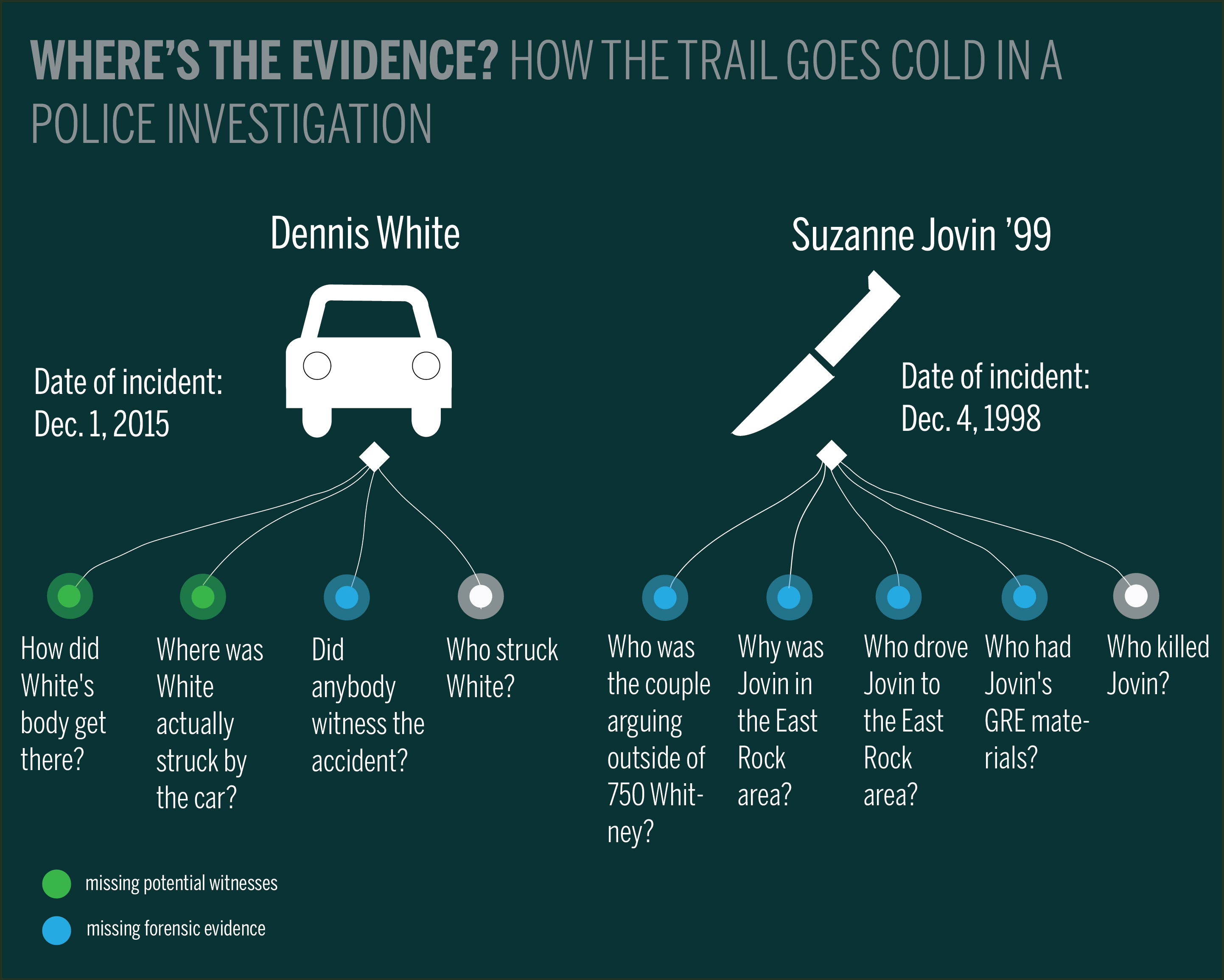

Days before the anniversary of Jovin’s murder, police officers were dispatched to the area of Davenport Avenue and Elliot Street after they received reports that a man lay bloodied in the street. According to New Haven Police Department spokesman David Hartman, doctors who examined the victim — Connecticut resident Dennis White, 37 — said his injuries indicated he was likely struck and dragged by a vehicle. But investigators found no evidence at the scene to suggest that White was struck by a vehicle at that location. He was in critical condition as of Dec. 2, Hartman said. Due to a lack of evidence, he added, police investigating the case are having difficulty determining how to proceed with the investigation.

Sometimes investigators have few leads, as in White’s case. But sometimes they pursue their leads for nearly two decades, as with the Jovin case.

“You can only investigate what you have to go on and what resources you can pour into it,” Hartman said. “And it’s unfortunate, but sometimes things don’t get solved. Sometimes a criminal will do a good enough job to clean up any evidence … Sometimes a municipal department might not have the ability to find minute evidence in every case. That’s the sad reality of it.”

Some cases have little physical evidence and witnesses fail to come forward. New Haven State’s Attorney Michael Dearington said that at a certain point, if a case is not moving forward, it may remain open without being an active investigation. Although White’s case has not been declared cold, Jovin’s case is currently under investigation by Connecticut’s Cold Case Unit.

The Cold Case Unit at the Chief State’s Attorney’s Office was established in 1998. According to Mike Sullivan, the chief inspector for the Connecticut Division of Criminal Justice, the office currently has 30 to 40 cases in its inventory, including the Jovin case. Kevin Kane, the chief state’s attorney, explained that his office has set up this cold case task force to work with local, state and federal law enforcement agencies to pool resources and investigators.

Sullivan explained that the Cold Case Unit compiles police reports, witness and victim statements, and any information that accumulated over the course of the original investigation. The unit then re-interviews people relevant to the case and retests evidence. Sullivan said it is a comprehensive approach with a team of scientists, detectives and lawyers.

“We take a systematic approach,” Sullivan said. “We go through the case from scratch like it wasn’t investigated before. We look at the case through fresh eyes.”

Sullivan said that as time passes, witnesses sometimes become more willing to open up and testify. He also explained that while other departments have new cases coming in every day, the Cold Case Unit has the luxury of being able to focus only on the selected cold cases.

Kane said though there has been no substantial progress on the Jovin case in the last year, he hopes that publicity might trigger a witness’s memory.

Jovin was found just before 10 p.m. on Dec. 4, 1998, on the corner of Edgehill and East Rock roads. When a Yale-New Haven Hospital physician who had been walking in the area found Jovin, she was alive and bleeding on the sidewalk after being stabbed 17 times. She died at Yale-New Haven Hospital that night.

In the past year, investigators have not uncovered any new substantial information about the events leading up to Jovin’s murder, Kane said. But investigators are still pursuing leads that may answer questions that could reveal important insights to the case.

On the evening of the incident, Jovin turned in her penultimate draft of her senior thesis on Osama bin Laden, and worked at a pizza-making party at the Trinity Lutheran Church for the local chapter of Best Buddies, an international organization that brings together students and mentally disabled adults. After returning to her apartment that night, Jovin told a friend that she was going to retrieve her GRE study materials from an unnamed person who borrowed them. After she logged off her computer, she returned keys from a borrowed University vehicle to the Yale Police Communications Center at Phelps Gate. She then left Phelps Gate and turned left on College Street at around 9:25 p.m.

Thirty minutes later, a 911 call was placed by a passerby to report that a woman had been stabbed. Kane said that given Jovin’s dress and the amount of time that passed, that it is very likely Jovin was driven to the area where she was found — nearly two miles away from campus.

“To this day, we don’t know why Suzanne walked out of Phelps Gate and turned left on College Street,” Kane said.

Kane said there are a number questions that the police are pursuing at this time.

According to a prepared release from the Chief State’s Attorney’s Office provided to the News, at the time of her murder, there were reports that a man and a woman were arguing outside of 750 Whitney Ave. Reportedly, a Caucasian man and a woman left the front entrance of the apartment complex at around 9:30 p.m. and walked between the arguing couple. Police still do not know who the couple leaving the apartment building was and are hoping that their identification may lead to information about who was arguing at the complex. Police are trying to determine if the woman involved in the argument was Jovin.

Police received several reports about an argument in front of the complex. A taxi cab driver in the area also reported an argument between a man and a woman in its vicinity. Police believe that the cab driver’s passenger — who was described in the release as a black woman in her late 30s or early 40s wearing a white outfit similar to a health care worker’s — may have information that can corroborate the driver’s witness reports. Police hope that new witnesses coming forward might reveal whether or not Jovin was involved in the argument.

Additionally, a woman who drove by the resident physician who rendered aid to Jovin after she was found stopped and asked if the resident needed assistance. The resident declined assistance from the woman, who had two children in her car. Identifying the woman as a witness who may have seen or heard something that she did not realize was important may provide crucial information to the investigation, Kane said.

“You can’t help but think that there might be someone out there with information,” Kane said.

There is not a huge body of physical evidence for the Jovin case, but Kane said this is not unusual. Sullivan explained that the vast majority of homicide cases do not have DNA evidence and that such cases are built on witness testimony. Sullivan said even if police find a fingerprint on a gun, that does not mean that the fingerprint belongs to the killer. Police and lawyers need eyewitness testimony to understand a case and corroborate other evidence.

Hartman said even if police have DNA from the blood of a perpetrator found at the crime scene, unless that person’s DNA has already been logged in one of the state’s databases, it does not serve as an immediate lead.

One such database is the Integrated Automated Fingerprint Identification System. Hartman explained that before IAFIS launched in 1999, police had to take fingerprints and manually compare them to individual fingerprint cards. According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s website, IAFIS is the largest criminal fingerprint database in the world and has an average response time of 27 minutes for electronic criminal fingerprints, with information submitted voluntarily by state, local and federal law-enforcement agencies.

“There are more and more cases that are cold that are being reinvestigated because of all of this new technology,” Hartman said. “There are great strides now in retaining forensic evidence [and] in retesting forensic evidence as new technology evolves.”

Hartman explained that even if police cannot link forensic evidence discovered at a crime scene to a perpetrator right away, if that person is later picked up for another crime, that evidence can link the person to the original crime.

Technology has changed the way that detectives investigate because of what some lawyers call the “CSI effect,” in which jurors trust DNA evidence over witness testimony. Sullivan said that people know that television shows, such as CSI, do not reflect the way real police work is done. Even so, he said, it give people unrealistic expectations about what evidence is credible.

“If DNA found at the scene is clearly the DNA of the person who committed the crime, I think jurors find that the most compelling evidence,” Dearington said. “I think everyone agrees now eyewitness testimony isn’t what it used to be.”

According to Sullivan, there have been around 1,100 unsolved homicides in Connecticut since 1980.