“Should I post this?” a student near me at breakfast asked his friend. “Overheard: remember when Overheard was funny?” Aside from confirming my firm belief that no worthwhile thoughts arise before noon, his sarcasm highlighted a seismic change happening within Yale’s social-media sphere. Overheard at Yale, once our largest Facebook recycling bin for all the mishegas said on campus, has become a civic commons for dialogue.

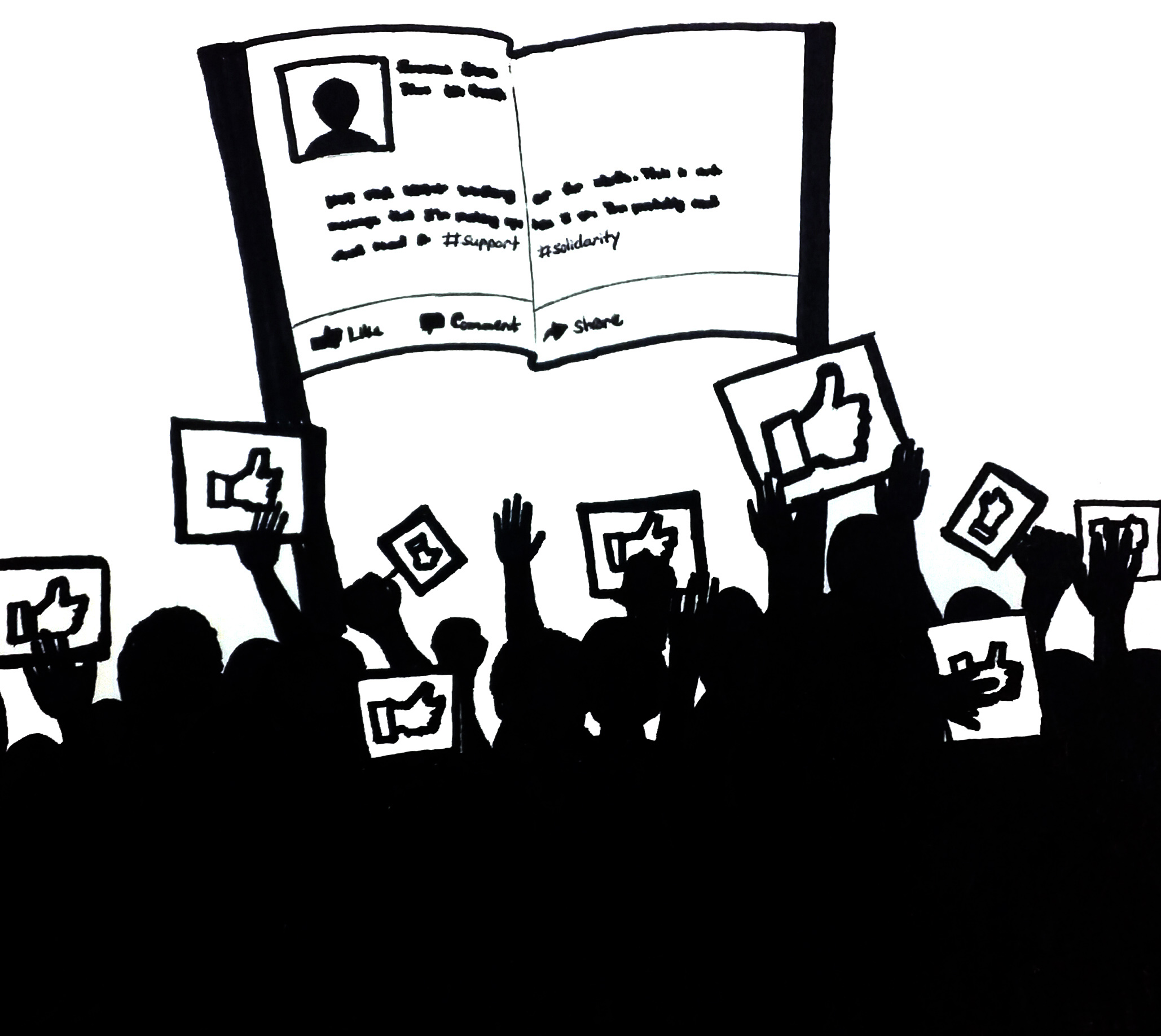

The evolution of Overheard is just one of the changing fault lines in Yale’s social-media climate. We repost articles from exterior media outlets, from the News’ opinion pages or from letter-like and essay-length statuses. The French flag flies over many of our profile pictures, just as a rainbow did this summer. A deluge of copy-paste #InSolidarityWithMizzou statuses flooded our newsfeeds. These reposted statuses and colored photos say to Facebook users “You don’t get to have access to your social-media news today. Today is not about your Facebook friends — today is about this event. Right now, this is what is relevant.”

Such postings and comment wars emphasize a new and basic truth: Facebook is our generation’s most powerful weapon in our collective communication arsenal.

Yet many see this weapon as little more than vanity activism: using issues to forage for likes. As the rapper T.I. says, “United we stand / Because we created a hashtag for Sandra Bland.” Unfortunately, T.I.’s words do describe a fraction of Yale. In an earlier moment of campus controversy, a friend succinctly condemned a vanity activist among us by quipping, “Yeah, of course she’s alright — she got 400 likes.”

Luckily for us, vanity activism categorizes only a sliver of Yale’s online community. More frequently, people post out of a vague awareness of injustice, without actually fighting for equality. Here, complaints about copy-paste activism bubble to the surface. Simply recycling written language seems passive: “Post an article, change your profile picture and — that’s it! That’s all you have to do. You’ve paid your social-civic dues — you’re now on the Side of Right.”

Most concerned-but-uninvolved Facebook users are, in fact, not social-media activists, but social-media sympathizers. These sympathizers, unlike vanity activists, post in good faith and from the best intentions. They know there are great, problem-filled chasms in our world, but they don’t do much to fix them, content to be lifted by the rising tide. There is some truth to the apathy criticism, just as there is some truth to the vanity criticism.

But let me clue you into an amazing little secret about social-media activism: It doesn’t matter to the success of the movement whether or not someone is a like-vulture, a lemming-poster or a megaphone-activist.

Why? Because social-media visibility serves a critical function: critical mass. A copy-pasting friend countered claims of apathy — correctly, I think — with the following addendum: “I lay aside my unease about copy-paste activism with the hope and intuition that voices in numbers wield power and the knowledge that this simple, clear message is a lot more important.”

Herein lies the crux of the matter. Social-media sympathizers are useful because they disseminate a message to others who are equally concerned but also uninvolved. With these postings, online voices join an offline chorus to affirm that “we out here, we been here, we ain’t leaving, we are loved” — we the inept-but-concerned allies, we the abstractly-interested-in-inequality intellectuals, we the photoshopped-profile-picture reposters. Social-media activism at its most effective gets people out from behind their screens and onto the streets for moments of face-to-face community dialogue. Regardless of the motive, this bandwagon-jumping enthusiasm fuels the momentum sparked by vocal community members who have a more direct personal stake in the issues at hand.

Look no further than President Salovey’s “Toward a Better Yale” email sent out Tuesday afternoon. Activists in our community used social media as an organizing strategy, their movement-minded hands and voices wielding the real megaphones. In part, this change comes from the energy of the social-media activists that managed to engage national media attention, whether or not the reporting was accurate. Gears are now turning in the great, creaky University apparatus called “The Administration,” gears that will push Yale forward. And with the turning of these gears come a more diverse faculty, better-funded cultural centers, better mental health services etc. The decision-makers of Yale have heard and are listening, partially because of our social-media response to racism. Public frustration has finally agitated the people who need agitating. With the help of Facebook’s “What’s on your mind?” prompt, we are now in motion. Another Yale is possible offline, and it’s in no small part due to the work of this online Yale.

Amelia Nierenberg is a sophomore in Timothy Dwight College. Contact her at amelia.nierenberg@yale.edu .