It looked terrible for Yale. There, in one of the nation’s most widely read newspapers, was an article about the University receiving $40 million in annual royalties from a drug that was too pricey to sell in places where the disease raged on. It was March 2001, and The New York Times had quoted a letter addressed to the Yale Law School students campaigning against the prices. The letter, which had been written in February by Jon Soderstrom, managing director of Yale’s Office of Cooperative Research, the body responsible for dealing with patents and licensing, read, “Although Yale is indeed the patent holder, Yale has granted an exclusive license to Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., under the terms of which only that entity may respond to a request.”

The law students, part of a group called the Yale AIDS Action Coalition, had responded with their own request: “If you say you’ve got this license agreement that doesn’t leave you any wiggle room, then let us take a look,” recalled Marco Simons LAW ’01, one of the law students in the coalition and now the legal director of EarthRights International. The Office refused.

An outside organization, Doctors Without Borders, contacted the University independently in March to ask if it would allow South Africa to import generics of the drug, d4T, which Bristol-Myers Squibb had priced at $10,000 to $15,000. The Office’s response was the same: their hands were tied.

The students, Simons said, were gearing up for a big campaign. But it would turn out to be unnecessary.

The OCR had drawn media interest, and within a month of the Times article, on March 14, the University announced that Bristol-Myers Squibb was lowering the price of the drug.

“When we started out, we didn’t expect the rapid movements we saw,” Simons said. “With my experience, with university organizations, you have to fight for a long time to get movement.”

He said he thinks the swift change stemmed from recognition that if the University did not do something, it would soon find itself in an “embarrassing” situation.

“They could see [the pressure] coming,” Simons said. By the time the Yale AIDS Action Coalition held its first public event, “[they] were basically declaring victory.”

As Simons described it, the issue at hand was twofold. First, the medicine’s cost was essentially pricing out entire populations. Second, Bristol-Myers Squibb was unwilling to allow the importation and production of generics in certain countries.

That was 14 years ago. “We turned out to be on the vanguard of something much bigger,” Simons said in retrospect.

RISING PRICES

In August of this year, a drug company called Turing Pharmaceuticals acquired the rights to Daraprim, a drug that treats a potentially fatal parasitic infection. A month later, the price of the drug jumped from $13.50 a tablet to $750. The founder and CEO of the company, Martin Shkreli, perhaps more widely known as the “Pharma Bro,” said the price increase was defensible — Turing, he told The New York Times, was just trying to stay in business. But no matter. He was skewered. The Daily Beast called him “Big Pharma’s Biggest A**hole.” The BBC dubbed him “the most hated man in America.”

The Shkreli episode was so extreme — the price of a single drug tablet increasing by nearly 56 times overnight — that it became a national outrage. But a drug’s price increasing substantially without any obvious increase in efficacy was nothing new. In August, Rodelis Therapeutics acquired a tuberculosis drug from the Chao Center and increased the price of 30 pills from $500 to $10,800. Under pressure, Rodelis returned the drug rights to the Chao Center in September.

And from October 2013 to April 2014, the price of a multi-purpose antibiotic called Doxycycline went from $20 a bottle to $1,849 a bottle.

Policymakers have taken notice. In just the last year and a half, at least six state legislatures have introduced pharmaceutical transparency bills, which would require manufacturers to justify their drug prices. A Massachusetts bill would allow the state to set a maximum price for a drug under certain conditions. And a Pennsylvania bill would exempt insurers from paying for a drug if a company failed to file a required report.

Hearing the conversation about drug prices, someone could be forgiven for thinking that pharmaceutical companies alone are responsible for research and development. But between a quarter and a third of new drugs originate at universities, in laboratories that are funded by the National Institutes of Health, which in turn is funded by taxpayers. The university then sells the intellectual property of those drugs to interested pharmaceutical companies, working out patent and licensing provisions via its Technology Transfer Office (Yale’s equivalent is the OCR). The university receives royalties. The drug companies — for the most part — can price the drugs as they wish. That is, unless the university gets a company to sign on to certain access provisions.

In 2014, the OCR negotiated 11 exclusive licenses for medicines or medical-related technologies, mostly with smaller biotechnology companies. None were for blockbuster drugs or discoveries like d4T, according to John Puziss, director of licensing at the OCR.

On average, the OCR will license between 10 to 20 patents per year, Soderstrom said. In each contract, the University and the company have to agree on a number of provisions: among others, how much will the University and the researchers get in royalties, under what conditions can the exclusive license be revoked and in which countries will the University file patents?

Yale has come far since the 2001 d4T incident, and, in 2014, the OCR managed to include global access provisions in nine of its 11 exclusive contracts. Those provisions vary, but according to Puziss, the OCR usually tries to get a specific one in each contract — an agreement that the company won’t patent in low-income and low middle-income countries.

“Our license template basically says that Yale won’t file patents in [those countries],” Puziss said. “That’s where we start off, and every time we do a license, that’s a negotiation. We’re generally pretty successful in getting that clause.”

Still, if the company doesn’t agree to it, the OCR has backup options. If a company insists on patenting in low-income and low middle-income countries, it will sometimes agree to non-enforcement agreements that exclude those nations.

There are certain exceptions to the non-enforcement provisions, but the gist is that companies will not prosecute patent infringements for the wrong reasons but will still have the legal backing to prosecute infringements for the right reasons.

According to Justin Mendoza SPH ’15, the President of the Yale Chapter of Universities Allied for Essential Medicines — an organization that advocates for increased university focus on global health issues — the provision is great, in theory. But in practice, it does not make much sense.

Non-enforcement agreements don’t have their own type of patent, Mendoza noted. And if you’re a generic company looking to produce a drug to which you know Yale has given another company an exclusive license, you would have no way of knowing that Yale wouldn’t prosecute you for patent infringement.

“Unless [Yale were to] contact every generic company in the country and say, ‘Hey, please feel free to make this,’ you would just not produce it,” Mendoza said.

If a company refuses to forgo patent filing in these countries, the OCR can try a pricing strategy: getting the company to sell its drug at less than 25 percent of the market value in the U.S. and other developed nations. The provision is meant to make the drug affordable, but again Mendoza is skeptical.

“It’s really arbitrary — it doesn’t match up to income,” he said.

Finally, if none of those options works out, the Office will try something that consumers might recognize from Ben and Jerry’s or Patagonia: the 1 percent approach. One percent of the company’s drug sales will be donated to a global health organization or to the governments of low- and low middle-income countries, either as a cash or in-kind contribution.

But according to Mendoza, that provision doesn’t do much either.

“The important part of the provision is either it’s 1 percent of profits made in low- or middle-income countries, or it’s 1 percent of all profits,” he said.

GlaxoSmithKline, the company that pioneered the 1 percent approach, opts for the former.

Though the approach might look good on paper, Mendoza said, considering that only 1 percent of the industry’s entire profit margin comes from sales in low- and low middle-income countries, that’s 1 percent of 1 percent of a company’s profit.

He paused to do the math. “We’re talking about a thousandth of their profit margin,” Mendoza said.

Some of the provisions may be less than ideal to access-to-medicines advocates, but they are undoubtedly a step up from what the Office had in the early 2000s, which was, essentially, nothing. No non-patent, non-prosecution or even percentage-of-market-price provisions.

According to Puziss, there was no pricing provision in the Bristol-Myers Squibb d4T contract, so the OCR could not do anything when the price skyrocketed.

Soderstrom said it was the d4T fiasco that led to these changes. “After the experience we had with Zerit [the drug name for the d4T compound], we became a leader among our peers,” he said. “We started with the Nine Points.”

The Nine Points is a document written in March 2007 by 12 universities’ technology transfer officers, and signed by a significant number of other universities. Among the document’s major points are that universities should “carefully consider” where they enforce their patents, and should also include provisions in their contracts that address the needs of neglected patient populations.

The document also called on all its signatories to adopt licensing policies that reflected their status as institutions built and maintained for the public interest, but its language was broad.

“We were criticized for the bland general statement,” Soderstrom said. So in 2009, the university, along with Boston University, drafted another document colloquially called the Statement of Principles. Its language was more specific.

The first section of the document, for instance, states that universities won’t patent drugs in developing countries or enforce patents when possible. The signatories also agreed that when they did award exclusive licenses, they would, when possible, incorporate certain provisions in their contracts. Among those: an agreement that the university wouldn’t prosecute patents in certain countries, would intervene if the company were irresponsibly developing or producing the drug and would set different drug prices for nations of different income levels. The signatories said that they would also include “agreements to agree,” requiring the company to sit down with the university if it turned out that the drug served an unanticipated public health purpose.

In between the signing of those two documents, Soderstrom said, Yale changed its own licensing policies — the university’s default would be to no longer patent in low- and low middle-income countries.

“I remember the conversation with Rick Levin [then President of Yale],” Soderstrom said. “Rick was a huge proponent of doing the right thing for the right reasons.”

“IT’S NOT PUBLIC PROPERTY”

The OCR, as its new provisions suggest, has evolved since the early 2000s, but by how much is still unclear.

While Puziss was willing to tell me about the provisions the OCR tries to include in contracts, as well as the number of companies with which it successfully negotiated those provisions, he was unwilling to talk about details.

When I asked him which companies had included which provisions in their contracts, he said it was confidential information. “These things are regarded as very sensitive business information,” he told me.

“Why?” I asked. “Weren’t these drugs developed with taxpayer money?”

“Would you show your mortgage or bank account statement to strangers?” he responded.

I asked Soderstrom the same question I asked Puziss. “[Pharmaceutical companies] don’t want to trade what they consider to be [confidential business] plans about the company and the investments they’re making,” he responded. “You’ve got to remember that the pharmaceutical industry is high-risk, long-term R&D, and the bets that they’re placing are very large.”

I asked about the Freedom of Information Act, the law that allows citizens to file requests to see almost all government documents. The contracts don’t have to be hyperlinked on the OCR website, but why aren’t they FOIA-able?

“The grants are,” Puziss said. But the licensing information? “It’s not public property.”

Both Gilead and Merck declined to comment for this article. Public affairs officials from Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), the trade group that represents U.S. pharmaceutical companies, said their group is not involved in decisions about access provisions, and that “how a company decides what to do on licensing is an individual company decision.” Though Bristol-Myers Squibb public affairs officials said they would connect me with someone on their corporate team, they did not. The companies refused to talk even about what they believe they are doing well in the field of access. And from the side of the OCR, the contracts are confidential, and neither Soderstrom nor Puziss were willing to make them anything but.

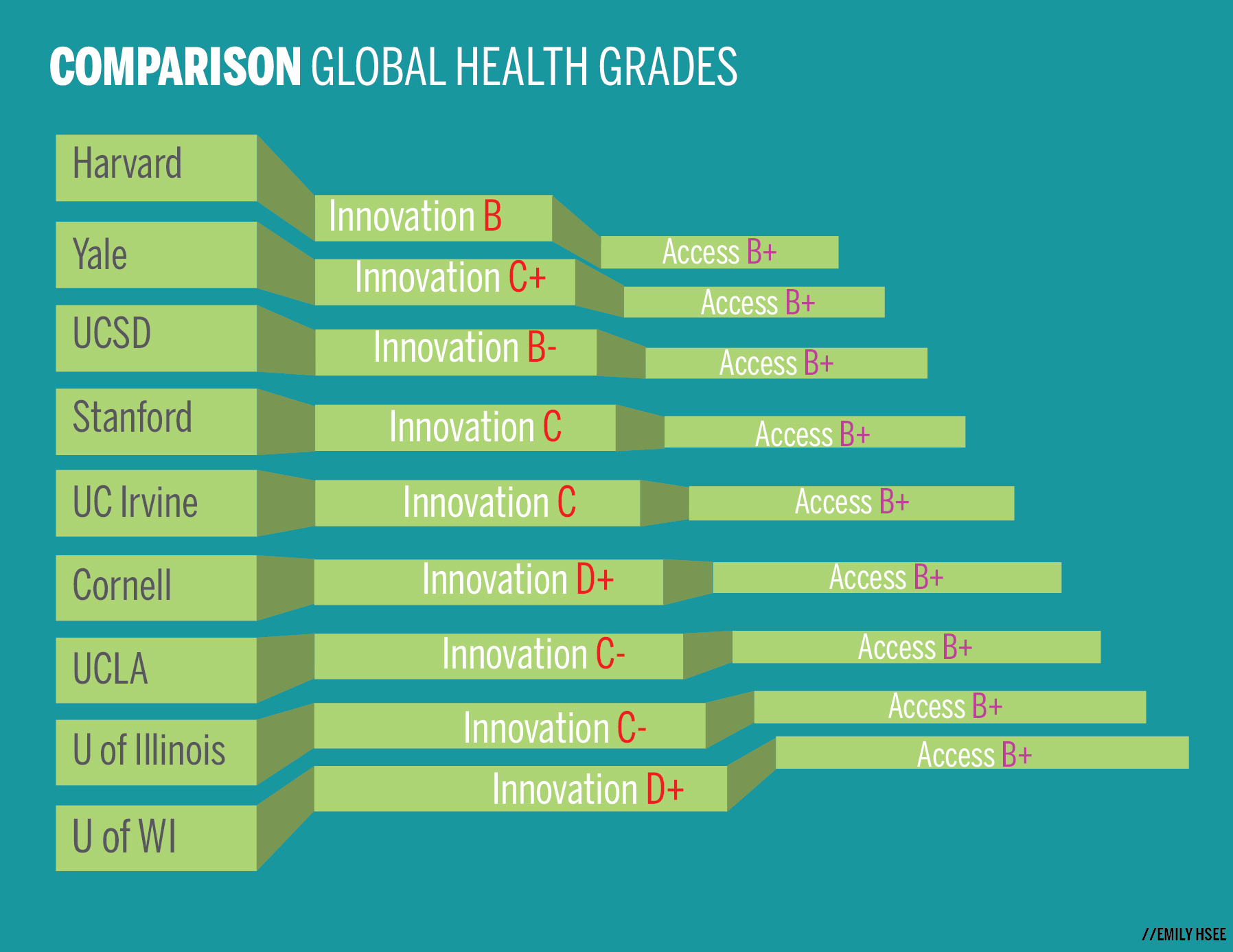

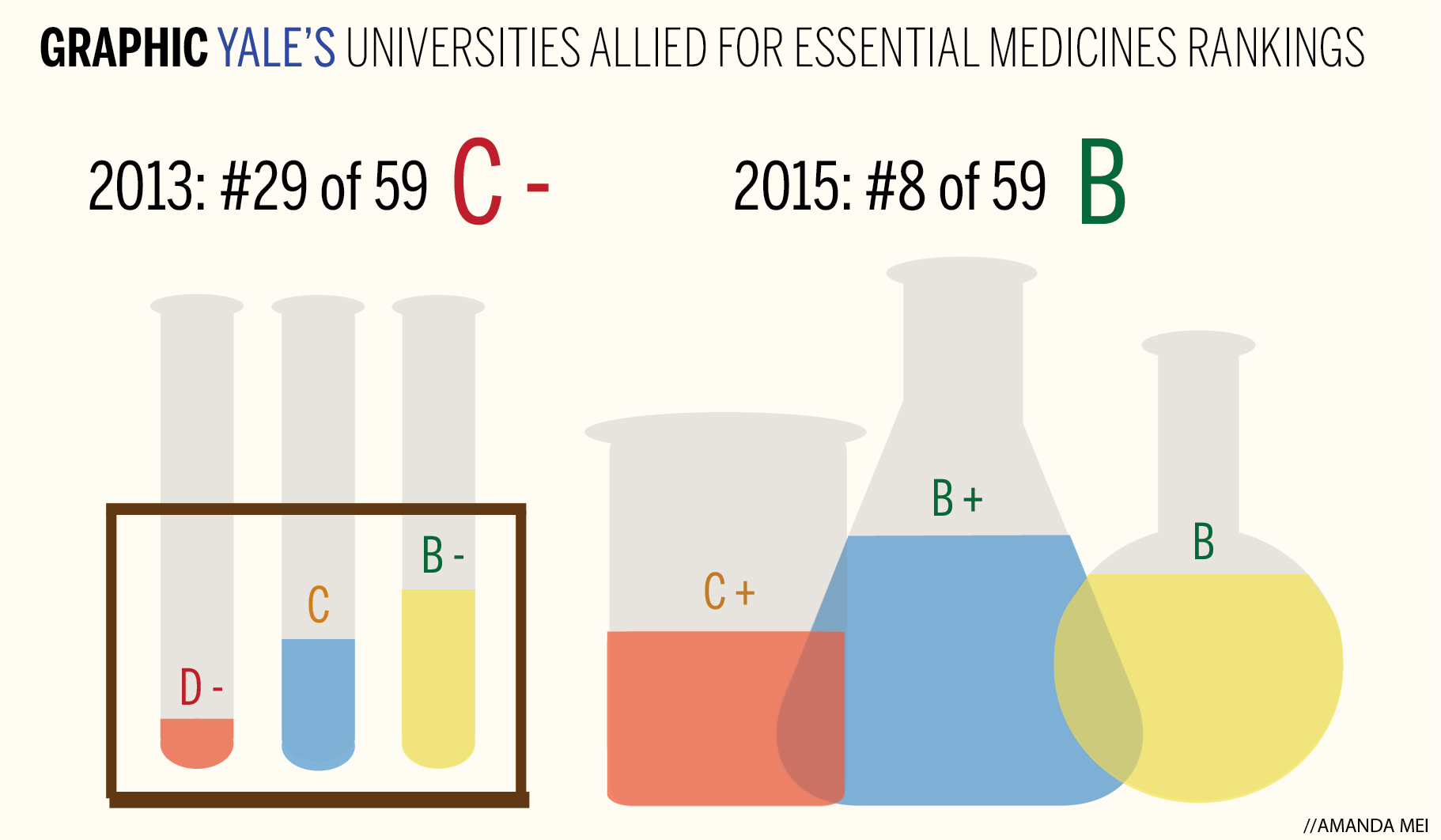

Despite signing on to both the Nine Points and the Statement of Principles, the University has done almost nothing to subject itself to outside accountability. In April, for the very first time, the OCR released information to Universities Allied for Essential Medicines, which was producing its second report card on universities’ research innovation, technology access policies and global health programs. The willingness to share information was a big step in transparency for the OCR — when UAEM was creating its first report card in 2013, the Office refused to share numbers.

Of the 59 universities evaluated in the most recent report card, released April 21, Yale came in 8th with a “B.” That was a significant jump from two years before, when Yale came in 29th and scored a “C-.” But the newest ranking still revealed issues with access.

One of the report card’s questions asks how often Yale pursues other access provisions when companies won’t agree to forgo patenting in low- and middle-income countries.

The preliminary answer on the survey is 81–100 percent of the time, but a follow-up survey question reveals that not a single one of these provisions included the biggest developing-world economies (Brazil, Russia, India, China, or South Africa).

Puziss said the question is not that relevant. Searching through the OCR’s database and starting in January 2014, he could not find a single time that the University had patented in Brazil, Russia or South Africa. He also said the University rarely patents in India, where the government has purposefully made patent protections weak. In these situations, additional access provisions are simply unnecessary.

Still, when the OCR does patent in India and China, the countries rarely benefit from access provisions. Together, those two nations represent 36 percent of the world’s population.

The last paragraph of the final point in the Nine Points document reads, “We recognize that licensing initiatives cannot solve the problem by themselves. Licensing techniques alone, without significant added funding, can, at most, enhance access to demands for which there is demand in wealthier countries.”

In other words, the question about whether university-developed medicines are being made accessible in the developing world isn’t just a question of access, of including certain phrases in contracts. Because it doesn’t really matter if there are systems in place to make medicines accessible if the medicines don’t exist — if they just aren’t being made. That second issue has nothing to do with patents and everything to do with the structure of the U.S. R&D system.

The R&D system in place today in the United States is relatively new. It began in 1980 with the passage of a bipartisan piece of legislation called the Bayh-Dole Act, signed into law by then-President Jimmy Carter. Before the Act, there was almost no commercialization of university research; any inventions made using federal funding had to be handed over to the federal government. The Act, for the first time, allowed universities to pursue ownership of their inventions.

According to Lisa Ouellette, an assistant professor at Stanford Law School who focuses on patenting under the Bayh-Dole Act, the change was necessary. Prior to 1980, she said, “the concern was that a lot of university researchers were doing cool things, but that the university wasn’t being used by society more broadly because there were no incentives to commercialize it.”

SUPPLY & DEMAND (AND THE PUBLIC GOOD?)

Before Bayh-Dole, universities were treated strictly as institutions for the public interest. But with its passage, universities now had an incentive to research commerciable drugs and technologies — that was where the royalties would lie. The change prompted questions about the purpose and future of universities. Would market demand begin to dictate university research? And how would universities remain accountable to the public when operating in a marketplace that responds only to supply and demand?

“One of the interesting things about the University selling off their research is [they] are nonprofit organizations, they’re taxed as nonprofits, but then they’re profiting off of their research,” said Hannah Brennan LAW ’13, a fellow at Public Citizen, a left-leaning federal advocacy organization.

According to Unni Karunakara, the former international president of Doctors Without Borders, the way that the U.S. allows universities to exercise intellectual property rights is unique.

In 2014, the average large research university spent 3.46 percent of its total biomedical research funding on global health research, training and collaboration, according to the UAEM report card. The majority of that money, though, was not spent on researching neglected diseases — viral, parasitic and bacterial diseases that have an outsized impact on low-income nations.

Though there was substantial variation in how much each university devoted to that type of research, the high was 28.1 percent and the low 0 percent. Yale’s score was particularly abysmal. Just 1.72 percent of the University’s biomedical research funding — half the average — was spent on global health research, training and collaboration. Of that, only 2.4 percent was spent on neglected disease research. In other words, just 0.04 percent of the University’s total biomedical funds.

According to Soderstrom, unfortunately, that research is simply not where the money lies.

“[Neglected and tropical disease drugs] are the hardest things in the world to try to license because they have the smallest market [of people who are able to pay for the drug], and they take just as much effort,” he said. “It’s just the nature of the capitalist, democratic system that we live in. If you’re a company that is beholden to its stockholders, what would benefit you the best is to invest in things that are going to generate significant profit.

Soderstrom said that at Yale, there have been instances in which researchers were pursuing vaccines for neglected diseases, but companies simply were not interested in licensing.

The system is not only skewed against the development of drugs for the world’s most impactful diseases. It is also skewed against pricing drugs, any type of drug, affordably. Even in the U.S., access issues abound. The irony, of course, is that those who have funded the development of the drug itself are the people being priced out of the market: the taxpayers.

Peter Maybarduk, the director of Public Citizen’s Access to Medicines Program, put it in more specific terms: “[The U.S. invests] $30 billion a year through the NIH, and then we give those technologies away to companies and allow them to charge consumers $100,000 a year for cancer treatments or $100,000 for a course of a Hep C treatment.”

Pharmaceutical companies usually say their drug prices are high because they need to recover the cost of R&D — they usually spend a significant amount of money to purchase the license from a university, or to conduct the R&D themselves.

But most of the experts I spoke with don’t buy the argument.

“When you start to look at the pricing [of drugs], it’s completely arbitrary — in certain countries, it’s priced differently,” UAEM President Merith Basey said. “They’re saying that they need to recoup their costs, but there are labs in Europe that have reproduced these drugs for $200.”

Brennan agreed. Drug prices simply aren’t based on R&D expenditures, she said.

“The narrative is breaking down for the pharmaceutical companies: they’re still saying they need to set prices high to account for R&D expenses, but it has become increasingly clear that they price drugs to maximize profits,” she said.

In fact, the pharmaceutical company officials themselves have already started to inadvertently tear down that narrative. According to Maybarduk, at a recent public forum, a Gilead official admitted that the company does not price according to R&D costs, but instead according to market prices.

Companies are able to do that partially because the U.S. federal government, unlike that in many other countries, lacks strong compulsory licensing abilities, said Ryan Abbott, a Southwestern Law School professor who specializes in health and intellectual property.

When I talked about this with Gorik Ooms, a human rights lawyer and the former executive director of Doctors Without Borders Belgium, he said the U.S. should look to India, where the government has made drug access a top priority, for a solution.

“If a public authority invests in a new medicine, then I think the intellectual property should stay with the public,” he said.

In fact, that’s the path a good number of countries besides India have opted for. According to Ouellette, Canada, the UK and Italy have all chosen to build a system that doesn’t incentivize pharmaceutical companies; the U.S. stands apart in how strong its incentives are.

India may be the developing world’s pharmacy, but it is the U.S. that is the world’s developer. Malaria, Ebola, influenza — all of these diseases are now treated or cured by drugs or vaccines developed in the United States. Lung cancer, heroin addiction? Treated or cured by drugs developed in university laboratories. HIV/AIDS? Once treated by a drug developed in Yale laboratories.

Soderstrom said that, since the d4T incident, leading academic institutions like Yale have started to pay attention to drug access. They’re trying to be proactive, “to be part of the solution as opposed to part of the problem.”

But the tension between the public and private spheres is still there. It probably always will be.

“In a sense, this [system] does cost taxpayers money,” said Abbott. “In another sense, private industry is how drugs get made.”

But to Ooms, who pointed out various alternative R&D systems, if people continue to believe that a private market is necessary, they are never going to make significant progress.

Karunakara agreed.

“The free-market economy — we work in that system. But that doesn’t mean we should not challenge it,” he said.

“This is not a song on iTunes. We are talking about life.”