Around 60 law enforcement officials, including New Haven Police Chief Dean Esserman, rallied against the country’s high incarceration rates at a Wednesday press conference in Washington D.C.

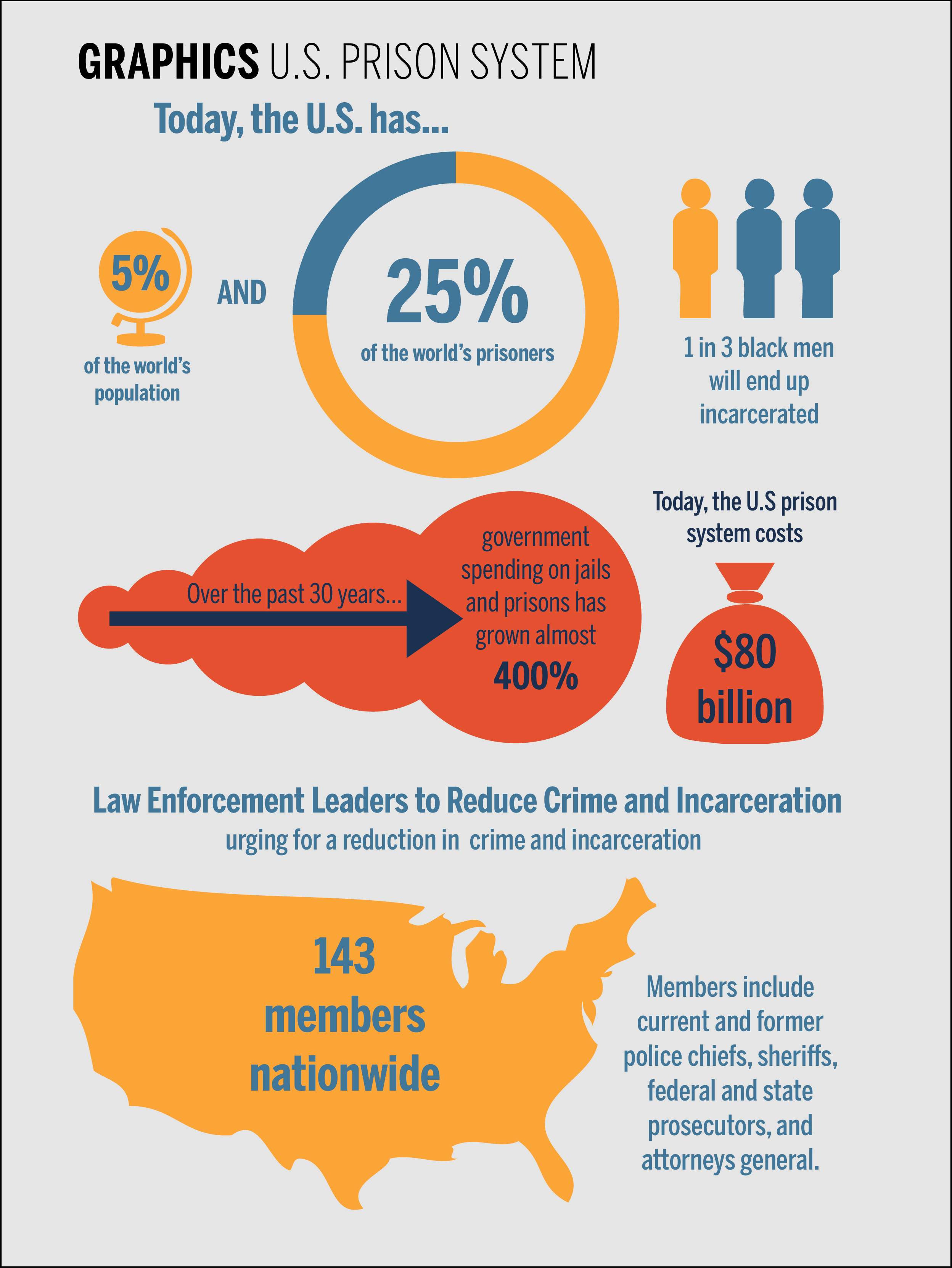

The attendees were members of Law Enforcement Leaders to Reduce Crime and Incarceration, a group of 143 current and former police chiefs, federal and state chief prosecutors and attorneys general committed to decreasing incarceration rates in the United States while taking a hard line on violent crime. Thursday, after the conference, the Senate Judiciary Committee passed the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act.

Wednesday marked the first official meeting of the Law Enforcement Leaders, who hail from all 50 states, but Esserman said New Haven has long been a leader in the national fight against mass incarceration. The city recently received $1 million to fight recidivism, with some of that funding allocated to reducing recidivism for juvenile offenders.

“There are many who deserve an alternative to prison,” Esserman said. “We need to come up with accountability and punishment, but accountability and punishment doesn’t always mean prison. Prison needs to be reserved for the most violent among us.”

Esserman said he is proud to represent New Haven, particularly after Mayor Toni Harp’s December visit to Washington D.C. to represent the Elm City at the U.S. Conference of Mayors. At that event, President Barack Obama lauded Harp and the city for connecting young people with supportive services such as My Brother’s Keeper, a mentoring program for disadvantaged youths that Obama launched.

Esserman said that after serving as a prosecutor and then as police chief for over 20 years, he realizes he has “put too many children in jail.”

He added that through his role as chair of the Juvenile Justice and Child Protection Committee for the International Association of Chiefs of Police, he has spoken with Attorney General Loretta Lynch about continuing the conversation about the criminalization of children.

“I think the punishment doesn’t just have to fit the crime, it has to fit the individual,” Esserman said.

Children’s brains take years to develop, Esserman said, citing research and outreach work conducted by the Child Development-Community Policing Program — an alliance between the Yale Child Study Center and the New Haven Police Department formed in 1991 — as essential to his understanding of juvenile justice.

The Child Development-Community Policing Program facilitates coordination between law enforcement and mental health specialists to effectively support children and families who have been exposed to violence.

“Children who have grown up in environments … rather than being harbors of safety and developmentally enhancing stimulation are in fact exposed to toxic stimulation in the form of what is objectively chaotic circumstances and at times horrifying circumstances,” Steven Marans, the director of the National Center for Children Exposed to Violence and founder of the Child Development-Community Policing Program, said.

Like Esserman, Marans said that simply punishing criminal behavior is not enough. Rather, it is important to understand where individuals come from, how they are doing emotionally and the nature of their family history, he said.

Marans added that criminal activity is generally viewed as having a singular source and singular solution.

“Not all violent behavior is the same,” Marans said. “The outcome may be … but the individuals who are engaged in these activities need to be thought about and understood in a more detailed way than often occurs in many places across this country.”

The state’s Office of Policy and Management and the University of New Haven’s Tow Youth Justice Institute were awarded $190,000 of the $2.3 million in total funding that Connecticut received from the federal Department of Justice. The funds are expected to improve outcomes for juveniles under community supervision.

Increasing alternatives to arrest is one of the four priority issues on which the Law Enforcement Leaders to Reduce Crime and Incarceration are focusing. The remaining three are restoring balance to criminal laws, reforming mandatory minimum sentences where necessary and strengthening community and law enforcement relations.

Nicole Fortier, the counsel in the Justice Program at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law, who serves as the senior coordinator for the Law Enforcement Leaders, explained that the group is responding to a national call for change in the criminal justice system.

“What this group is doing is coming together and saying that as law enforcement they know for a fact that [current] policies need not be there to keep crime down,” said Fortier. “They know that you can reduce crime while reducing incarceration.”

Fortier cited the statistic that though the United States makes up 5 percent of the global population, it is home to 25 percent of the global prison population. Further, she noted that these incarceration rates are a significant expense for the country. It costs $80 billion a year to run both prisons and jails, excluding the cost of law enforcement and courts, she said. The Law Enforcement Leaders’ focus on violent crime as opposed to petty crime aims to protect the communities while avoiding unnecessary mass incarceration, she added.

Esserman, Marans and Fortier all said attempts to simply punish negative behavior out of society have proven unsuccessful.

The Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act, which enhances mandatory minimums for certain crimes while establishing recidivism programs and limits on solitary confinement for juveniles, enjoyed bipartisan support.

The act includes elements of February’s proposed Smarter Sentencing Act, which aims to reduce mandatory-minimum sentencing for controlled substance offenses. Richard Davidson, Rhode Island Press Secretary for Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, explained that Thursday’s bill is more comprehensive.

“These policies will better equip inmates to pursue productive, crime-free lives after prison — helping to reduce prison populations, cut costs and make communities safer,” Whitehouse, a Senate Judiciary Committee member, said in a press release Thursday.

The Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act passed in committee by a vote of 15–5.