As the Greater New Haven Water Pollution Control Authority looks to add another town to its network, a lawsuit against the city and the authority may cause complications.

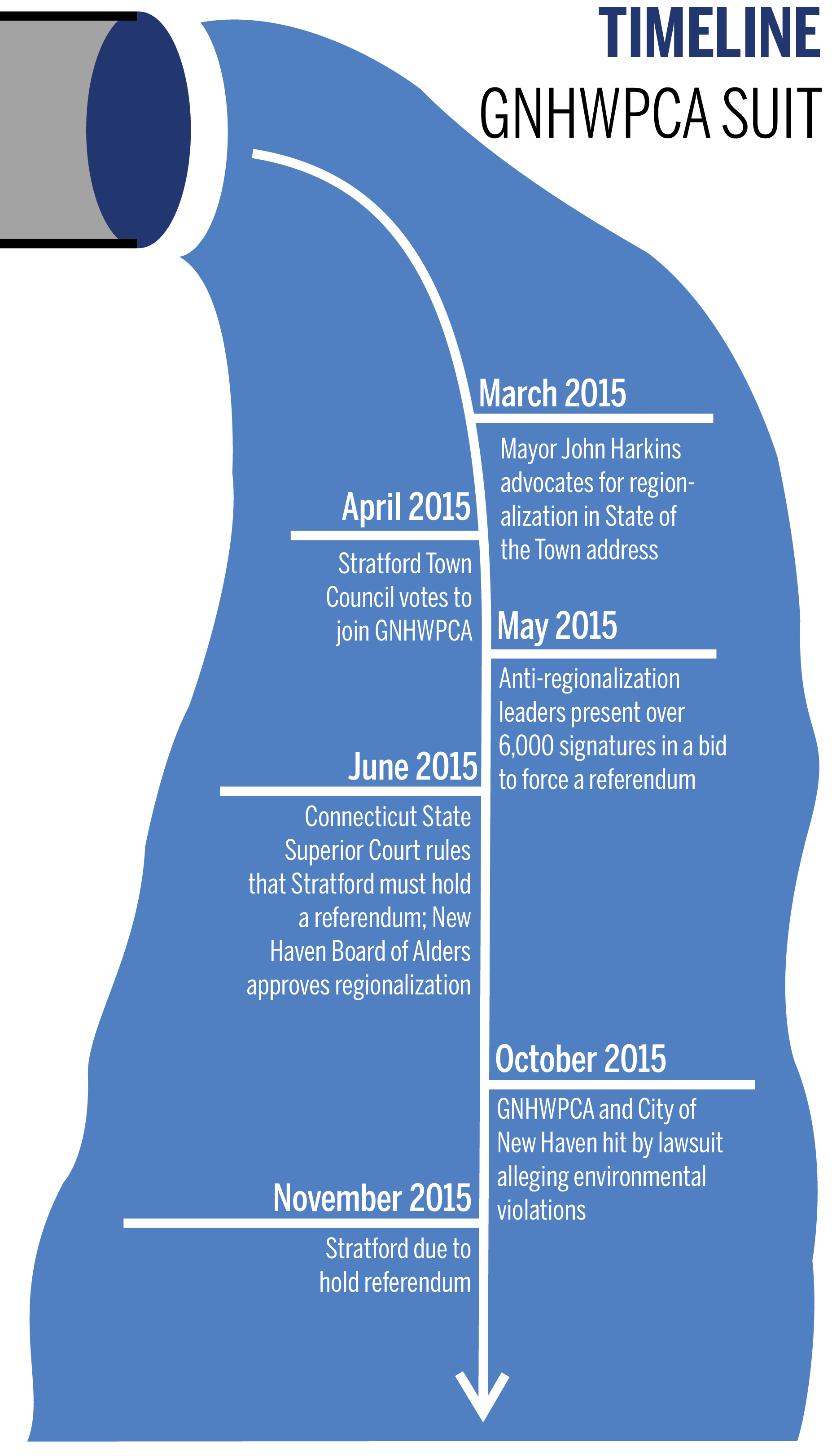

The GNHWPCA and the City of New Haven were named as defendants in a lawsuit filed on Oct. 2, in which plaintiffs, 26 Crown Associates — the Philadelphia-based owners of an apartment building in the Ninth Square neighborhood — have alleged that negligence on the part of the GNHWPCA has left their building’s basement prone to flooding with sewage during storms. The plaintiffs also alleged that the GNHWPCA and the city have violated the Clean Water and Connecticut Environmental Protection Acts by discharging raw sewage into Long Island Sound during storms and other instances of heavy rainfall.

The lawsuit comes a month before Stratford is due to vote on joining the GNHWPCA by selling its wastewater treatment plant and bonded debt to the authority — a move that voters call “regionalization.”

The New Haven Board of Alders approved this regionalization in June, but a citizen-led push in Stratford for a November referendum on regionalization delayed the merger. If it goes through, Stratford will have joined New Haven, Woodbridge, East Haven and Hamden as members of the GNHWPCA.

Christopher Rooney, the plaintiffs’ attorney, said the GNHWPCA’s current infrastructure is not equipped to handle the volume of sewage it currently carries. He said 1,500 residential units are due to come online to the sewer system — an influx that might add to strain on the current system.

Much of the sewer system in New Haven does not currently carry storm water and regular wastewater in separate pipes, the plaintiffs said in the lawsuit. They alleged that this failure to separate causes the release of raw sewage onto their property during “significant weather events” that lead to flooding in the area. The plaintiffs alleged that this phenomenon occurs on other properties, not only their own.

Lynne Bonnett, a New Haven environmental activist who has often confronted the GNHWPCA over alleged environmental violations through her work with the New Haven Environmental Justice Network, said much of the area between the West River and the Quinnipiac River has a sewer system that combines storm and wastewater. Bonnett added that the city has known the combined sewer system to be a problem since the early 20th century, and the GNHWPCA is currently in the process of digging up and replacing pipes and separating the systems.

According to the lawsuit, the plaintiffs seek three forms of restitution. The first is money damages for the flooding, which Rooney said amounts to a “temporary taking” — government appropriation of property for a limited amount of time. The plaintiffs also seek a temporary injunction against the city further expanding the user base for the sewer system until it can protect against overflows into the Long Island Sound and private properties. The third form of restitution aims to force the city to perform infrastructure improvements to prevent backflow onto private properties and reduce discharges into the Sound.

The last demand might prove particularly burdensome for the City, Rooney said.

“When they fix the system, it’s going to take tens of millions of dollars,” he said. It’s expensive enough that the city has chosen not to do it for 15 years … The city doesn’t seem to want to remedy it because to fix it, they’ll have to spend a lot of money on water tank installation & repair.

Rooney said the plaintiffs’ allegations of Clean Water Act violations are made under “citizen’s suit standing” — a clause in the Clean Water Act that allows citizens to sue if they witness violations.

City Engineer Giovanni Zinn ’05 did not return request for comment. Annex Alder and GNHWPCA Chairman Alphonse Paolillo Jr. directed requests for comment to the authority’s attorneys.

Catrina Kohn of Robinson & Cole LLP, the law firm representing the GNHWPCA, said in a Friday statement that the authority denies all allegations.

“The GNHWPCA denies any liability and states that it is operating its system in accordance with its lawfully issued regulatory Permits and Consent Orders,” the statement read.

The statement also said that the GNHWPCA is in “constant communication” with the state Department of Energy and Environmental Protection so as to be notified of any compliance issues.

Work on sewer separation in the area around Trumbull Street occurred throughout 2014. Sewer separation efforts are meant to stem “combined sewer overflow” events, which often occur during storms and leak raw sewage into rivers that flow into the Sound.

New Haven currently has 22 active CSOs, a large number of which are located around the Mill and Quinnipiac rivers. A 2011 survey by the GNHWPCA found that the removal of all city CSO locations would cost at least $550 million. The plan for removal involves separating combined sewers in Downtown and Fair Haven and constructing tanks to store excess combined wastewater.

From May 2014 to April 2015, the GNHWPCA saw a total of 172 CSO events, totaling 27.7 million gallons of discharge. That figure is significantly lower than the previous year, which had 297 CSO events totaling 104.2 million gallons of discharge.

Now that the Elm City and GNHWPCA have been served with the lawsuit, Rooney said the defendants will have 30 days from Oct. 2 to file a response. That filing deadline means that the lawsuit will not approach resolution until long after Stratford votes on whether to join the GNHWPCA on Nov. 3.

According to Henry Bruce, treasurer of the anti-regionalization “WPCA Get Answers” group and a talismanic figure in the anti-regionalization movement, it is not yet clear whether the lawsuit will influence the impending Stratford referendum over regionalization.

The Stratford Town Council approved selling the Town’s own WPCA to the GNHWPCA in the spring, but a petition movement garnered enough signatures — roughly 7,500 in a town of 33,000 voters — to force the town to hold a referendum on the proposal in November. Stratford Mayor John Harkins took the petitioners to court, claiming state law did not require a referendum. But the Connecticut State Superior Court sided with the petitioners in June and put regionalization on hold.

Harkins’ Chief of Staff, Mark Dillon, did not respond to request for comment on the Town’s reaction to the lawsuit.

Bruce said the lawsuit goes a long way toward supporting many of the points made by the anti-regionalization movement.

“I don’t know that it will greatly influence it one way or another,” he said. “But it’s basically another example that supports our claim that, down the road, if the sale goes forward, the GNHWPCA has huge capital expenditures ahead, and all rate payers in the regional authority will bear the brunt of the capital expenditures.”

Rooney echoed Bruce’s sentiment. He said all taxpayers in the authority’s jurisdiction — which would include Stratford residents if the deal passes — will finance any capital improvements to the GNHWPCA system that the lawsuit demands.

But Stratford’s geographic separation from New Haven means that the proposed regionalization would be only a financial merger, not a physical one. Stratford’s sewer system would continue to serve Stratford exclusively, so any updates to New Haven’s infrastructure would not affect the town.

Bruce said the referendum has taken on a significance beyond just the question of regionalization. Much of the discontent over the regionalization plan centered on how the Stratford’s administration has handled it. Critics say the Town Council passed the deal too quickly, without enough time for public input.

“I don’t think it’s a partisan issue. I think it’s a Stratford citizen taxpayer issue,” Bruce said. “I would say that this has become a referendum on Harkins and a referendum on our elected officials acting fiscally responsible.”

The diverse party affiliations of residents who have signed the petition for a referendum prove that regionalization is a largely nonpartisan issue, Bruce said.

With three weeks to go before the vote, Bruce said he is optimistic about the anti-regionalization movement’s chances.

“I’m confident of success,” he said. “I think in the next three weeks, we’re going to go through a process of reminding everyone what they learned in the springtime — remind them that this is not a good deal for the town’s taxpayers, remind them that the mayor wanted to deny us our rights.”