Jessica Yuan ’15 had no idea what kind of salary to expect right out of college for a job in architecture. During her junior year, she thought she might earn $60,000 annually after leaving Yale. But when she finally did the research in the fall of her senior year, she learned that the starting salary for an entry-level architecture job is about half that. She was shocked.

“It’s really strange that we’re making major life decisions about the fields we’re going into without knowledge of the salaries [they entail],” Yuan said.

Yuan finds the conversation about money and salaries at Yale to be minimal at most. She attributes this to Yale students’ idealism — the faith that we will have freedom to do as we wish careerwise, and that we will gain a foothold in any field we enter.

Other students didn’t talk about their salaries until second semester senior year, she recalled, which is when the whispers began. To do otherwise would have been impolite, Yuan said.

***

In recent months, national media has revived the age-old debate of college rankings. Publications from the Washington Post to the Hartford Business Journal have picked up on several newly released studies, this time backed by the quantitative evidence of alumni salaries. And if we take these reports at face value, Yale does not seem to be faring well.

In late August, the Washington Post ran an article on “[where] to go to college if you want the highest starting salary.” The article used a report from PayScale, which collected salary data from nearly 1.5 million employees with degrees from over 1,000 different American colleges. The result “isn’t kind to Ivy League schools,” the article concluded, noting that Yale alums rank 40th nationally, and third-to-last among Ivies.

A couple of weeks later, a different Washington Post article in September was kinder to Ivy League schools. Citing data released by the Department of Education, the article revealed that the median annual salary for an Ivy League graduate 10 years after college enrollment is twice that of the average college grad. Still, the Post noted that Yale ranks second-to-last among the Ivies. Yale’s 90th percentile lagged significantly behind that of Harvard — in other words, even Yale’s top earners are falling short.

Even in Connecticut, Yale seems to be merely on par with other schools. In a study released this month, the Hartford Business Journal reported that the starting salaries of graduates from Fairfield University — a private school with an enrollment of about 5,000 — averages $50,100. In comparison, Yale graduates earned $50,000. Other private schools in the state, such as Quinnipiac University and Trinity University, have comparable averages, at $49,500 and $47,800, respectively.

The common question here seems to be whether Yale, a prestigious and storied institution, is “worth” attending. And in terms of salary, recent studies suggest that it just might not be.

These studies and the media’s attention to graduates’ salaries raise several questions: Are Yalies actually doing worse than their peers financially after graduation? And — perhaps more importantly — should we judge life after Yale by how much we make?

***

Upon closer investigation, the data upon which these articles are based do not encompass all Yale grads. Rather, the studies tend to focus on specific subsets of alumni.

The Department of Education College Scorecard data, for instance, looks specifically at students who were on federal financial aid, quantifying their earnings 10 years after college enrollment. While roughly half of Yale students were on financial aid in the 2009–10 academic year, only 10 percent received funds from the U.S. government to complete their education, according to the College Scorecard.

The PayScale study, on the other hand, reports only median income in two categories: that of alumni with zero to five years of experience, and that of alumni with 10 or more years of experience. According to alumni interviewed, this is misleading due to the number of Yalies who go to graduate school or switch between sectors during their first five years post-graduation. Moreover, the Washington Post coverage of the study also takes graduate students into account.

Even when considering only undergraduate degree holders, PayScale ranks Yale (46th) not only behind Ivies like Brown (35th) and Cornell (32nd), but also behind public universities such as the Georgia Institute of Technology (22nd) and the University of California, Berkeley (18th).

Still, it seems an oversimplification to summarize the experiences of thousands of Yale graduates in a single median income statistic. The numbers may indicate that we’re lagging behind, but the paths of recent graduates tell a more complex story.

***

For the class of 2010 — whose salary data many of the studies focus on — the Great Recession loomed heavily over their career choices.

Jonathan Gordon ’10, an economics major, said he had considered entering the financial sector after spending two of his college summers interning in the field. Ultimately, Gordon chose to attend law school, and now practices law at a firm in New York City.

Analyzing salary data for those who have only recently graduated isn’t particularly fruitful, given the number of students who don’t make a living in graduate school, Gordon said. He added that entrepreneurs don’t earn much in their first few years either.

“There tends to be a lot of affluence as well as financial aid at Yale, so students can afford to go to grad schools or work on political campaigns to set [themselves] up in the long term,” Gordon said.

Gordon highlighted a campuswide focus on finance during his time at Yale, with firms heavily recruiting students for lucrative and prestigious positions. However, he noted that the financial crisis — which began in September 2007 — redirected many of his peers’ career paths, drawing them to less traditional fields. Aspiring businessmen became teachers; corporate hopefuls became civil servants.

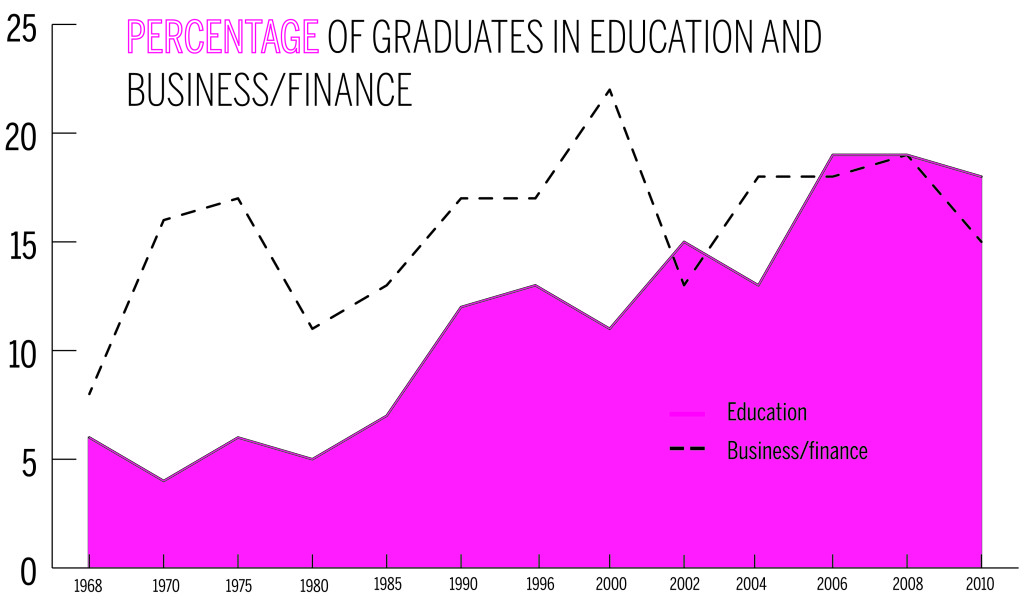

According to a study conducted by the University’s Office of Institutional Research, employment in areas of business and finance dropped to 15 percent for the class of 2010, compared to 22 percent in 2000. The study also demonstrated Yalies’ growing interest in the education sector, as the number of students entering the field steadily rose from 4 percent in 1970 to 18 in 2010.

For Jason Acosta ’10, who had been considering working on the Hill as a Democrat, the 2010 midterm elections played an even bigger role than the financial crisis in determining his career path. Following the elections, the Democratic Party lost many national and state seats, leading to a scarcity of job positions within the Party.

“Everyone was scrambling for jobs,” Acosta said. “The limited opportunities made me reassess what I wanted to do.”

Acosta took an offer to direct a volunteer project at the Hispanic Youth Institute despite the job’s relatively low salary. He said he made the decision because he thought the work would be rewarding, and he hoped to give back to his community. Nevertheless, he admits that there was an element of serendipity to his experience.

“Everything happened very quickly. I kind of just fell into it,” Acosta said.

Money wasn’t a major concern for Andy *, a 2010 graduate who majored in political science and now teaches at a private school in California.

Although Andy originally planned to work on the policy side of education, a teaching assistant job he held as an undergraduate in the New Haven Public Schools District drew him to the classroom. He acknowledged the limitations of his lower salary, but stressed that he values more than what’s in his bank account. In fact, when Andy moved to California, he chose the lowest-paying job offer out of those he received because the school’s values aligned with his own.

“Obviously, it would be nice to have more money, but the question is at what cost?” Andy said. “Sometimes people don’t really take those other kinds of non-monetary costs into account when making decisions.”

Still, like Gordon, Andy felt the constraints of the financial crisis on his job search. He had considered law school as an undergraduate, but abandoned the notion after the recession. Other students he knew avoided professional schooling, which they associated with accruing debt.

While the 2008 recession made some ’10 graduates re-evaluate the tried and true route into the financial industry, the class of 2010 also defined broader trends in graduates’ post-college plans. Seventy-five percent of the class entered the workforce directly — a historic high at the time, while only 21 percent attended graduate or professional school right after Yale.

“There was this mentality at the time: ‘There must be lots of other people out there in worse condition than we are. At least we’ve gone to this great school with great connections. If there are jobs out there we’ll probably get them,’” Andy said. “I definitely heard a lot of people saying things like that.”

***

“At our fifth-year reunion last spring, only one person I talked to was still doing the job he had started out at,” Austin Anderson ’10 said. “And he just quit recently.”

Anderson added that graduates expect to explore a range of different pursuits, which makes it easier for them to justify short-term career choices. This trend among millennials is not Yale-specific either. In 2012, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported the average worker stayed at a job for 4.4 years, while a survey by Future Workplace found that 91 percent of people born between 1977 and 1997 anticipated staying at their job for three years or less, causing Forbes Magazine to declare job-hopping the “new normal” for millennials.

This culture of career fluidity also highlights a struggle between practical constraints and ideological pursuits. “People always say you can come out of Yale and make a lot of money, or save the world,” Anderson said.

Other alums interviewed generally agreed. They said many of their friends worked for a couple of years at large firms both to repay student loans and to take advantage of training resources in the private sector. Many then went on to join startups, nonprofit organizations and the education sector. However, some graduates also went in the opposite direction, moving from programs such as Teach For America to law firms, Gordon observed.

Balancing money and meaningful work also plays into graduates’ decisions to enroll in graduate and professional school. Anderson, who now attends Harvard Law School, noted that its generous financial aid will allow him to work in the public sector afterwards without the full burden of debt. Still, even for someone who seems to have found that balance, Anderson admitted that he struggles to reconcile financial success and worthwhile endeavors.

“There is a definitely a tension — this is a choice you are constantly asked to make,” he said. “You can make it during your junior year when you go to a McKinsey information session, or five years after you graduate.”

Entering a market still reeling from the financial crisis, the class of 2010 was forced to consider opportunities beyond well-worn career paths. And five years later, they continue to define a generation in flux.

***

Over the last five years, unemployment has dropped closer and closer to pre-recession rates as the U.S. economy recovers. But for Yale’s most recent graduates — the class of 2015 — the same concerns remain: How does one find a job that both pays and fulfills? Are finance and consulting worth it or not? And what about grad school?

Despite the nationwide economic upturn, money remains central to these questions. The Department of Education’s assessment focused on graduates who received federal financial aid, which naturally raises the question of whether students on aid place a different value on financial success.

Austin Long ’15, currently a Yale-China Fellow teaching English in Hong Kong, said that students he knew who were on financial aid certainly took salary into consideration when pursuing careers post-graduation. But these students didn’t necessarily jump for the highest-paying jobs, nor opt for consulting — instead, they chose to balance personal financial stability with community-oriented work.

“I want to be rich just like most people, but that desire to be rich is balanced by [a desire to] make a meaningful impact with all these privileges and benefits that I have accrued as result of my education and Yale degree,” Long said. “The most important thing for me is to give back because I wouldn’t have gotten here today without the help of other people.”

Shibao Pek ’15 said that, ultimately, being on financial aid has only a secondary impact on how students choose careers. Whether one prioritizes earnings or career satisfaction is determined more by the personality of the individual student, he said.

According to Erica Leh ’15, while students on aid think about money differently when making such decisions, more affluent students have no right to judge the jobs chosen by others. She cited a trend of students “occupying,” or protesting, recruiting sessions in order to prevent others from entering finance.

“I know some Yalies who entered the finance sector from incredibly well-off backgrounds, and some who came from poverty, so I think the idea of lumping everyone into a group of ‘sell outs’ is misguided,” Leh said.

Like the class of 2010, the most recent graduates seem aware that what they do in their first few years out of college might not define the trajectory of the rest of their careers.

The Office of Career Strategy’s preliminary report for the class of 2015 highlights that financial services, consulting, education, technology and healthcare/medical/pharmaceutical are the top five industries that these graduates have entered. And 30 percent of students who entered the workforce after graduating this May began at some kind of nonprofit, NGO or government or other public entity.

However, some are skeptical of whether these sectors will remain the most popular options in the long run. Citing the prevalence of two-year contracts among companies in finance or consulting, Pek believes that in the vast majority of cases, graduates who go into these industries don’t plan to stick around for the long haul. Though education also features heavily in the industries that 2015 grads go into, Pek isn’t particularly optimistic about its long-term retention of graduates either.

“Regarding [Teach For America] and other short-term education contracts, basically everyone I know is doing it as a stepping stone to something else,” Pek said. “Trust me, I’m in this industry myself.”

Although ’15 Yalies seem to express many of the same financial constraints and uncertainties as their predecessors, they also face a different challenge — they have entered a market in which the technology sector is taking an increasing share of high-paying jobs. These range from cushy startup gigs to positions at industry giants like Microsoft and Google, both of which were among top employers for the class of 2014. According to OCS data, the computer science and technology industry has ranked in the top five industries graduates have entered for the past three years.

In a survey conducted by the News, approximately one-third of 2015 grads who reported making $90,000 or above annually majored in computer science at Yale.

Such a growing focus on tech after graduation led Pek to observe that “tech is the new finance/consulting, and the kids who are willing to ‘sell out’ are very much aware of this.”

Yuan added that while finance and consulting are often perceived as “sell-out” industries, tech has been relatively spared from the label so far.

Money evidently matters to some extent for the class of 2015, regardless of where they are working or what they are doing. Still, alumni from the classes of 2010 and 2015 certainly don’t think that median income statistics can adequately describe how Ivy League schools match up with each other. Many don’t believe, for instance, that the Washington Post article which ranks Yale second-to-last income-wise in the Ivies necessarily indicates that Yalies are more dedicated to service or education, or more averse to finance.

“Let’s not kid ourselves into saying that our median salaries are $10,000 less because we’re somehow higher-minded than Harvard grads,” Robert Peck ’15 said.

***

Yuan, who now works at a local architecture firm in New Haven, said that what hinders conversations about money and how much of it we make after Yale is often the fear of appearing petty or greedy or mean.

But what these conversations — which Yuan and other alumni agree don’t occur nearly enough — reveal isn’t simply just how much one graduate makes in comparison to another, or who decided to go into banking.

“[They’re] not supposed to draw you into the mindset of every man for himself,” Yuan said.

Instead, talking about how we’re going to make a living after Yale means that we can broach related topics of financial aid and class in voices louder than a whisper; we can address the social pressures and expectations that accompany “selling out.” We can question whether going into finance or consulting necessarily has to mean “selling out” at all.

And we can afford to be more transparent about what matters to us not only in making a living after graduation, but also in making a life.

*Name has been changed to protect privacy.