Though the Perkins Loan Program — the oldest federal student loan initiative — will not grant any new loans as of the end of September, Yale students already receiving federal money will not be affected.

The program, which was founded in 1958 and has since provided $36 billion to 30 million low-income students, was not renewed last fall, but was automatically extended by one year. Though Congress made a last-minute attempt to save the program, the bill was blocked in the Senate after passing through the House of Representatives. While Perkins Loans have made higher education more accessible for low-income students, the program has been criticized for unnecessarily complicating the federal financial aid process and acting as a superfluous alternative native to the Stafford Loan Program, which has lower interest rates.

“It seems like in the last 10 years, every year we were on the brink of the [Perkins] program’s demise,” Director of Financial Aid Caesar Storlazzi said. “It’s finally happened.” Storlazzi added that he supports the government’s wish for a simpler aid system.

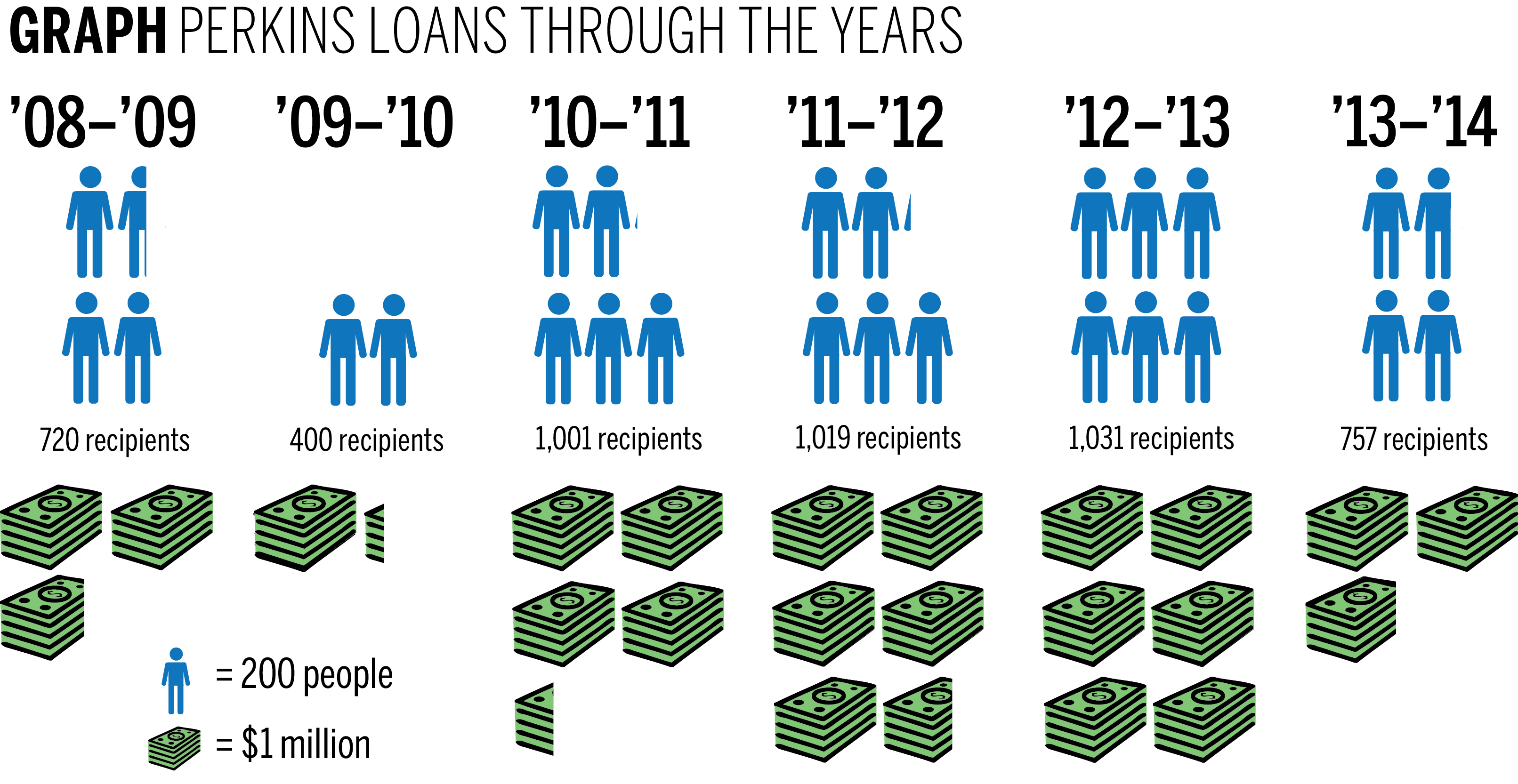

Though the Perkins program has officially run its course, students currently receiving Perkins Loans will continue to receive funding for the next five years. Perkins Loans are only given to students from Yale’s graduate and professional schools, with loans allocated to the schools based on the need of their students, Storlazzi said. Perkins Loans have not been made available to undergraduates since Yale College adopted a no-loans policy at the start of the 2008–09 academic year.

For the coming academic year, no new Perkins Loans will be extended, prompting students to look to Stafford Loans or Direct Loans for the additional funds. Mark Kantrowitz, vice president of the financial aid and higher education consulting firm Edvisors Network, said Stafford Loan limits were increased by $2,000 in 2008 with the expectation that they would eventually replace the Perkins Loan. Since then, Kantrowitz said, colleges have absorbed the additional funds while the Perkins program went on for longer than anticipated.

“I don’t think many students will notice that the Perkins Loan Program is gone,” Kantrowitz said.

Currently, the annual expenditure of Yale’s Perkins Loans is equal to about 1 percent of Yale’s roughly $350 million grant budget, Storlazzi said.

The Perkins fund has gradually dwindled over the past few years. The last federal contribution was made in fiscal year 2009, Kantrowitz said, and since then there have been no new federal capital contributions. The program’s assets has been depleted due to an inability to collect loans, loan forgiveness and fees associated with managing the fund, he said.

Perkins has loan forgiveness policies that make the loans advantageous for students who plan to work in certain fields after graduation. For example, students who go on to pursue careers in teaching, law enforcement and nursing are eligible for loan forgiveness.

Tyler Blackmon ’16, head of last year’s Yale College Council task force on financial aid and a staff columnist for the News, said the Perkins Loan Program’s expiration provides the federal government with an opportunity to funnel those assets into different aid programs geared toward low-income students.

“There’s potential for a lot more federal funding to go toward college affordability in different ways,” Blackmon said, adding that Congress could choose to extend the Pell Grant program, for example. “If we’re devoting federal money away from that program and towards something more grant-based, then I think that has the potential to be a better system.”

Pell Grants are financial aid awards given to low-income undergraduate students by the federal government, and they do not need to be repaid.

Blackmon said that if Congress decides not to replace the Perkins program, low-income students will bear the burden. In theory, Perkins Loans are supposed to go toward students with exceptional need, but Kantrowitz said that in practice, they have the same distribution as Stafford Loans.

However, many are protesting the end of the Perkins Loan Program — a petition to save it has received over 20,000 signatures so far on Change.org, a website that allows users to create online petitions.

“The students who count on a Perkins Loan to help pay for their college education shouldn’t be left high and dry when the program expires,” Michigan Rep. Mike Bishop said in a press release from the House of Representatives’ Education and the Workforce Committee.

Kantrowitz said many colleges may set up their own institutional loan programs to replace the Perkins Loans, though Storlazzi said Yale has no plans to do so.

“There’s been no discussion to set up an institutional loan program to replace Perkins,” Storlazzi said, adding that some professional schools, including the School of Medicine, already have institutional loan programs.

Schools that have historically received Perkins funding may be forced to pay back a portion to the federal government. Storlazzi said while he expects Yale will have to return some funds, he does not yet know how much. He added that the federal government will likely give the University more details by the end of December.

In the 2013–14 academic year, the Perkins Loan Program shelled out over $1.2 billion to 539,000 students nationwide.