The divide between New Haven’s wealthiest and poorest residents has continued to widen over the past decade, with a recent Bloomberg report ranking New Haven 39th in the country for the highest income inequality. But the inequality extends beyond income, to domains as far-reaching as education, housing and transportation. In the first of a three-part series on Elm City inequality, Erica Pandey investigates the drivers and implications of the persistent achievement gap in New Haven Public Schools.

Read the second installment of the series, on the divided housing landscape in New Haven, here.

Before he was elected president of the New Haven Federation of Teachers, David Cicarella taught two classes to eighth-graders at a New Haven public middle school — one in math and one in English.

Cicarella’s math class, an accelerated algebra class, had some of the brightest students in the school, while his reading class, a remedial course, taught to eighth-graders reading at second- or third-grade levels.

“The algebra students came to me well-prepared,” he said. “I did all the same stuff, but the results were very different. At the end of the day, the other students had gone through some very challenging circumstances and a lot of it was out of my control. All teachers face this.”

Cicarella’s experience is representative of the inequalities within the New Haven Public Schools system, where, according to some education experts, factors outside of teachers’ control often play a larger role in determining test scores than does instruction.

A 2013 report by nonprofit organization DataHaven found that 58 percent of third-graders from high-income families in New Haven were at or above the state’s standard reading level; only 17 percent of lower-income students were at that level.

But New Haven’s stark achievement gaps do not stem from a lack of investment in education. In fact, the past six years in New Haven have been characterized by a decided push to bolster youth services in the Elm City, with the creation of the comprehensive education reform initiative, New Haven School Change, as well as the scholarship program New Haven Promise.

Yet achievement in New Haven schools continues to lag behind the majority of school districts across the state.

QUANTIFYING THE GAP

This past spring, nearly 95 percent of New Haven public and magnet school students in grades 3 through 8 and 11 took a new set of standardized tests with both math and reading components — the Smarter Balanced Assessments.

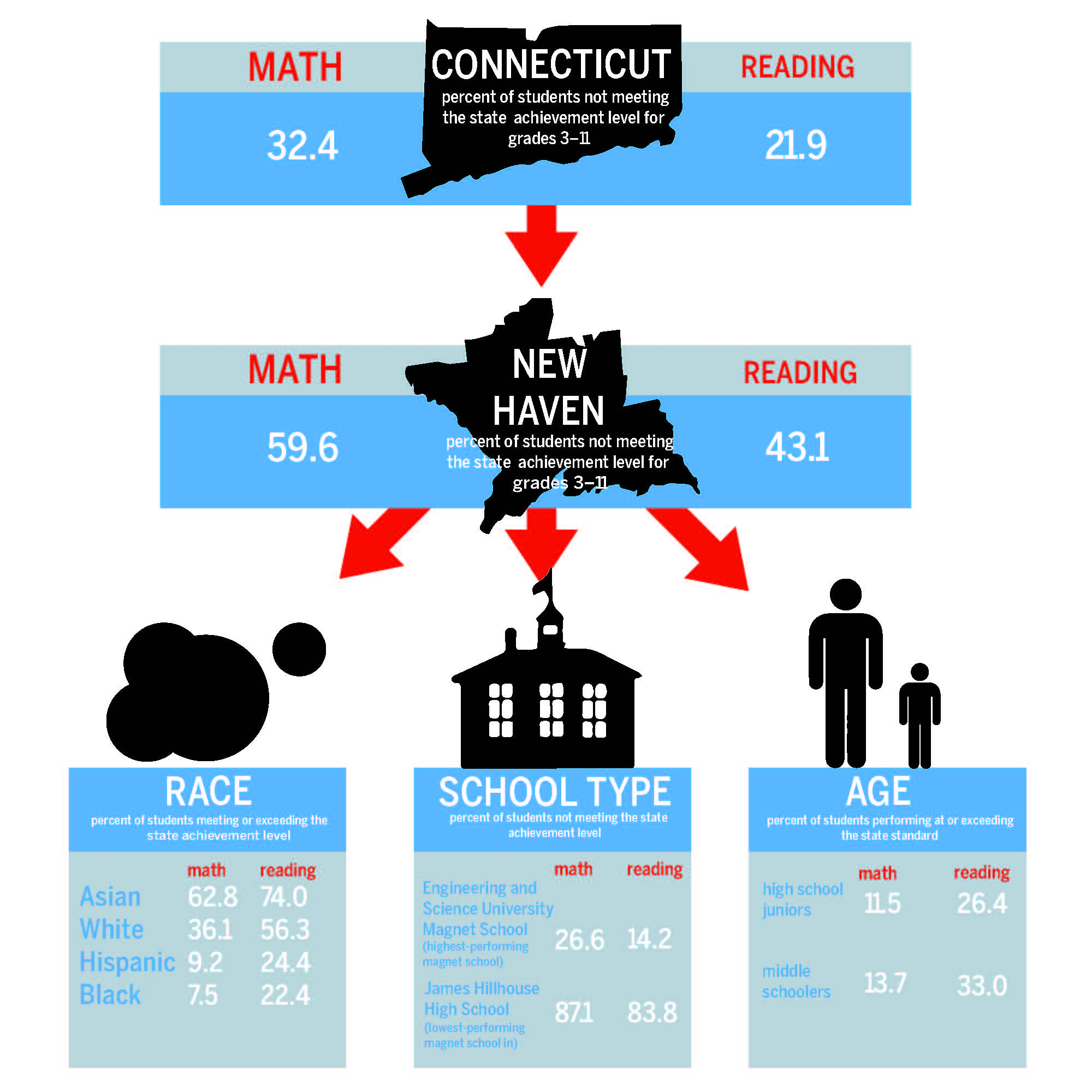

After months of anticipation, results of the tests were released last month, showing that in both subjects, many students statewide were not meeting minimum standards for college readiness. Across the state, 32.4 percent of students in grades 3 through 11 failed to meet minimum standards for math and 21.9 percent of students did not meet the minimum level of achievement for reading.

But these results were met with scrutiny by teachers and education experts, many of who questioned the validity of the eight-hour test administered on computers. A survey of 1,600 Connecticut teachers found that 97 percent thought the test was not a good measure of school effectiveness, and many expressed concern that the lengthy test was not suitable for young children.

According to Mayor Toni Harp, New Haven’s low test scores may have been a result of limited technology instruction at schools. Several students were unable to complete the computerized sections of the test because they were uncomfortable using the software, Harp said.

Cicarella echoed Harp, adding that there is always a learning curve with new testing methods.

“Every time you shift the test, you shift instruction, you shift material,” he said.

But even if the standardized test is a flawed measure of achievement, the results do paint a dire picture of student achievement in New Haven, where the share of students below minimum standards was nearly double that statewide. Nearly 60 percent of students scored below the achievement level in math, while 43.1 percent did not meet the level in reading. Only five school districts in Connecticut ranked below New Haven in reading achievement, and only three districts reported larger percentages of students below the minimum achievement level in math.

“The test scores show a lot, and we cannot ignore them,” Cicarella said. “If there are kids in the eighth grade reading at a third-grade level, we darn well have to do something about it.”

But, Cicarella said, for urban school districts like New Haven, student progress is a more apt measure than an assessment of aptitude. He added that although many New Haven students score lower on standardized tests, their personal growth in the areas of reading and math is often promising.

A major challenge for the school district to overcome, Cicarella noted, is that many students entering NHPS are hindered by factors at home. Those issues, moreover, are outside the control of school administrators.

“There’s a lot we can do on our side of the fence, but there’s also another side,” he said. “Kids come from where they come from, and they are where they are. We start working from there.”

AREAS OF CONCERN

A closer look at Smarter Balanced test scores indicate larger achievement gaps among students of color, lower-income students and English Language Learner students within New Haven.

In New Haven, the highest-achieving students were Asian and white, with 62.8 percent and 36.1 percent meeting or exceeding the state achievement level in math, respectively. Asian and white students also performed best in the reading tests — 74 percent of Asian students met or exceeded the state’s standard and 56.3 percent of white students did so.

Black and Hispanic students scored significantly lower than other races across the district. In math, only 7.5 percent of black students met or exceeded the achievement level, and 9.2 percent of Hispanic students met or exceeded the standard. The percentages of black and Hispanic students scoring at the state standard for reading were 22.4 and 24.4 percent, respectively.

“I don’t think the test scores are surprising, although alarming,” said Rev. Eldren Morrison, pastor at Varick Memorial AME Zion Church and education reform advocate. “As soon as our African-American and Hispanic students get to kindergarten, they’re already behind. We have to focus on early childhood education, so there’s not so much catch-up involved later on.”

The Smarter Balanced test results also showed that ELL students scored lower than native speakers, likely due to language barriers.

According to a DataHaven report released in January, 25 percent of NHPS students speak a language other than English at home. The most common language, the report said, is Spanish, with 4,795 NHPS students speaking Spanish at home.

The gap extends even further, with magnet schools performing significantly better than non-magnet schools in New Haven.

This trend is not surprising, said Coral Ortiz — a junior at James Hillhouse High School and student representative on the Board of Education. Ortiz said that magnet schools tend to attract higher-performing students and that the smaller class sizes allow for more student-teacher interaction.

At Hillhouse, which is not a magnet school, 87.1 percent of students did not meet the state standard of achievement in math and 83.8 percent did not meet the level in reading. The New Haven high school that reported the highest scores was the Engineering and Science University Magnet School. At ESUMS, only 26.6 percent of students and 14.2 percent of students fell below the achievement standard for math and reading, respectively — both lower percentages that the state averages.

David Low, a mathematics and aquaculture technology teacher at the Sound School — one of the city’s magnet schools — said higher scores at magnet schools are not necessarily due to better teaching methods.

“Poverty plays the biggest role,” he said. “We have fewer kids of poverty than other schools. Quite frankly, we could be doing nothing different and still getting higher scores.”

A HOLISTIC APPROACH

According to Ward 1 Alder Sarah Eidelson ’12, the School Change and Promise programs are important pieces of the puzzle, but not the whole solution.

Eidelson, who also serves as the aldermanic Youth Services Committee chair, highlighted the city’s violence prevention programs such as Youth Stat — which identifies at-risk youth based on rates of school absence — and the violence prevention grant, which allocates federal funds to several city initiatives targeting youth violence, including job training and community service programs.

“When we’re looking at the question of how to support young people in New Haven such that they can be successful, it’s important to look at the whole picture,” Eidelson said. “The challenges that students face are in school but they are also before school and after school.”

Harp echoed this sentiment, noting that gaps in achievement and youth violence are linked.

“If someone in their teens doesn’t have the adequate skills to succeed in school, they’re likely to be the ones who are disruptive as a way to not have to own some of that lack of achievement,” she said.

Harp added that the academic training has been incorporated into city violence prevention efforts. This summer, she said, a group of youth returning to the community from the juvenile justice system was offered tutoring in reading and math as well as team development through New Haven Youth Stat. The graduates from the program, Harp said, gave overwhelmingly positive feedback and said the tutoring specifically helped them prepare for high school coursework.

Harp said the city would be assembling an advisory committee on reading, composed of members from within the community as well as outside. Experts from the University of Connecticut Neag School of Education and the Haskins Literacy Initiative — a Yale-funded program — will be among the committee members, she added.

Harp added that, to address the achievement gap in math, the city will look into utilizing online resources such as Khan Academy to supplement school curriculums.

The process of addressing gaps among different NHPS schools revealed by the test scores will be a long-term project, she added.

“We have a portfolio of schools that are performing poorly compared to others,” she said. “We’ll take a cold hard look at that and begin to make those changes in the places that need them most.”