The Yale Computer Science department has been criticized for its emphasis on theoretical over practical knowledge, and recent media coverage has painted the Yale CS undergraduate education as leaving students ill-equipped to get jobs in the tech industry. But alumni in tech told a different story. In fact, the fundamental skills Yale students learn may be the perfect preparation to excel in an ever-changing tech landscape. Stephanie Rogers reports.

Sporting a Dropbox T-shirt he had received the semester before at a technology career fair, Michael Hopkins ’15 gesticulated excitedly, laughing at his own outfit.

“They give out so many tech-related shirts at these job fairs that basically anyone in tech has a shirt from at least every major [tech] company,” Hopkins, a computer science major, said.

Though he wears the logo of a company worth $10 billion — a valuation which has more than doubled since late 2011 — Hopkins will actually be working at one of the U.S.’s better-known tech companies after he graduates. Valued at $395 billion, Google offered Hopkins a job as an associate product manager. According to Glassdoor, the baseline annual salary for the position of associate product manager at Google is slightly above $120,000.

With a Computer Science Department that ranks 20th in the nation, according to U.S. News & World Report, and is smaller in size than those at many of Yale’s peer institutions, recent news coverage has centered on a gloomy thesis: Yale students are finding it hard to get jobs in Silicon Valley. Stanford, often cited as a feeder school for the tech industry, produced over 200 computer science graduates last year. Meanwhile, Yale produced only 48, including students who participated in computer science joint majors with other disciplines.

But faculty, students and alumni interviewed told a different story. Any Yale computer science student who wants a job in Silicon Valley can get one, they said.

GETTING HIRED

Among the group of those who say finding employment in Silicon Valley is easy for Yale graduates is Kevin Ryan ’85, founder of Gilt Groupe, Business Insider and MongoDB. He graduated from Yale in 1985, and, by 2011, he was the only executive to have created a $1 billion New York tech startup twice.

“It’s completely false,” Ryan, who is also a member of the Yale Corporation, said. “If you hunted down all of the computer science graduates from last year, I would bet you anything all of them are employed and all of them are doing great.”

Brad Rosen ’04 GRD ’04, Yale lecturer in Computer Science who teaches a course on the intersection of law and technology and graduated from Yale with a simultaneous bachelor’s and master’s degree in computer science, said he was completely stunned by the media coverage claiming that Yale students could have a hard time finding jobs after graduation.

Speaking specifically about a March Bloomberg Business article — titled “Want a job in Silicon Valley after Yale? Good luck with that” — he scoffed.

“It’s simply not true,” he said.

To prove his point, he began rattling off dozens of names of students. Intermittently, he would take a breath to add that this was just a few names compared to the larger number who have gone on to found successful small startups or have prominent positions at established technology companies. Some Yalies have gone on to create tech companies ranging in the billions — Pinterest, Gilt and MongoDB, for example. Then, he launched into more names.

With more and more companies needing computer science and engineering majors, demand far exceeds supply, said Thaddeus Diamond ’12, who now works at Amazon as a software engineer.

Sam Gensburg ’11, who co-founded a startup in the San Francisco Bay Area called Student Blueprint, said he believes the misperception that Yale students have a harder time getting into the tech world may come from the fact that there are simply fewer Yale CS grads than there are at Stanford.

“It’s funny when you’re talking to people around Silicon Valley, and you say you went to Yale. It gets a lot of respect, but it’s also something people have never heard,” Gensburg said. “Stanford CS grads are like a dime a dozen. There just aren’t very many of us [Yale students], so we don’t make much of a footprint even though we are doing okay.”

It is not just that there are fewer CS graduates from Yale. It is also that Yale’s student body itself is simply smaller than that at other schools like Stanford and Harvard.

Stanford enrolled 7,019 undergraduates this academic year, according to the university’s Common Data Set, published online. In 2014, it conferred bachelor’s degrees in computer and information sciences to 12.25 percent of graduates. In contrast, when Yale graduated 1,344 undergraduates in 2014, only 3.5 percent of those majored in computer science or a joint major between computer science and another discipline.

“I don’t know where anyone got the impression that Yale CS students are not prepared for careers in technology,” said Michael Giuffrida ’13, a software engineer in the Chrome Division of Google, in an email, adding that the University is a target for Google, Microsoft and New York-based startup companies. “They each spend thousands of dollars to recruit us, which is saying a lot when we have so few students.”

Charlie Croom ’12, who works as a senior software engineer at Twitter, said that the company only makes real recruiting efforts at Stanford, MIT and Harvey Mudd.

Yale’s CS Department is comparatively small, and investing the money for travel expenses does not pay off when the company would probably only get three or four qualified applicants, Croom added. In contrast, visiting MIT usually yields around 15 sure hires. Stanford, he pointed out, also happens to be a about a 30-minute drive away from Twitter.

According to the Yale Class of 2014 First Destination Survey, 7.5 percent of graduates reported post-graduate employment at a technology or engineering company with a heavy technology focus. Of those graduates, only a third chose to begin their technology careers in California.

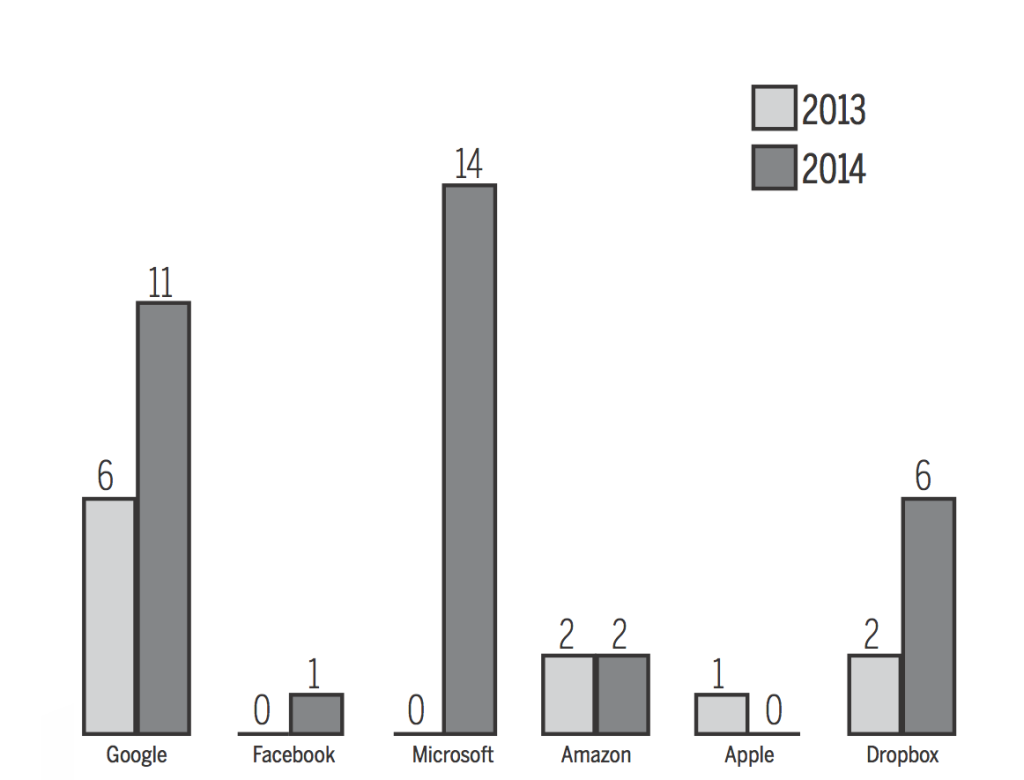

Still, for the class of 2014, Microsoft was the fifth-most common employer of all Yale students — hiring 14 graduates — following the University itself, Goldman Sachs, McKinsey and Bain & Company.

A FOOT IN THE DOOR

According to many students interviewed, though people say that the University’s Computer Science Department falls behind, carrying the Yale name helped in getting the job they wanted.

By the Harvard-Yale Game, most of Croom’s CS friends had gotten job offers. In contrast, Croom was, in his own words, “a little late to the party.” He had not realized that the easiest way to acquire jobs in the industry was to have someone refer you, he said.

Later, after he had submitted resumes to companies, “the Yale name gave me the opportunity to get my foot in the door,” he said.

Hopkins got his job at Google after completing an internship at the company. That internship Hopkins got through a recommendation from a friend working at Google.

Connections in the industry are not only important in getting jobs, but also in figuring out which ones are the best fit.

According to Stephany Rhee ’16, it is much easier for students to decide which companies to pursue if they can reach out to friends who are willing to share experiences and recommendations.

As more Yale students take internships in Silicon Valley, their classmates will have the opportunity to learn from their experiences.

Last summer, only two Yalies interned at Facebook. This summer, six students have already confirmed they will be interning at Facebook. But Rhee said the company made offers to even more students who have yet to decide.

Yale has tremendous alumni support in Silicon Valley, said Jeanine Dames, assistant dean of Yale College and director of the Office of Career Strategy. OCS has recently released resources to help students make these connections, including an employment evaluation database, a list of where all graduates from the past two years are working and a list of where people have been employed over the summer.

Hopkins said he has noticed an increased number of tech-related job events in his four years at Yale. He pointed out that the OCS fair having a specific place where students interested in tech could drop their resumes was a sign of progress.

And it is not just the University facilitating these efforts.

According to Jason Brooks ’16, a computer science major, bigger tech companies, especially Facebook, have recently been reaching out more to Yale undergraduates, where he will be interning this summer.

Brooks helps coordinate campus “Tech Talks.” The talks feature representatives from both large and small companies speaking about engaging topics relevant to the tech community. At the end of the talk, the companies, which this year have included bigger names like Google and Microsoft, recruit students.

In addition, events like YHack — an annual hackathon started in 2013 — not only foster a stronger community around tech culture and give practical experience to those who have had fewer opportunities, but also offer a forum for larger tech companies and startups to recruit.

EMPLOYED, BUT PREPARED?

Faculty, alumni and students interviewed had different views about whether a Yale computer science degree is meant to prepare students for a job in industry. If Yale is a liberal arts school, then the logic behind that educational model ought to extend to the computer science major, the majority of faculty, students and alumni interviewed argued.

When Gensburg, who co-founded Student Blueprint — an academic and career services advising website for community college students, is looking to hire, he searches for applicants who have strong backgrounds in computer science fundamentals and can learn languages quickly. He is less interested in those who are good at programming, but lack the building blocks necessary to adapt in an ever-changing landscape of new computer languages.

Computer science fundamentals and programming are not the same thing, but it is crucial that students understand the former to be successful during the interview process, students and alumni explained.

Although companies say they value the fundamentals, some students interviewed said they dislike the department’s emphasis on what they say are outdated programming languages like C and Scheme.

One of the major’s core classes, “Introduction to Computer Science” or CPSC 201, has students use only Scheme. Some students questioned why the department does not place a heavier emphasis on languages like Python or Java, which are more widely used in the tech world today.

It is not that these languages are completely absent from the curriculum. According to Alex Reinking ’16, CPSC 112, “Introduction to Programming,” for instance, teaches Java. “Systems Programming and Computer Organization” or CPSC 323 has students use either Python, Perl or Ruby for some assignments. Other courses, like CPSC 439 “Software Engineering”, have no set language, so some students might opt to use Python, he added.

But according to Devon Balicki ’14, these “coolest new frameworks” and languages do not matter as much as students think they do. Balicki, who works in the technology division at Goldman Sachs, said that strong knowledge of data structures and algorithms — the fundamentals — are crucial to the job and are harder to pick up after college.

At Goldman Sachs, she met Ulrich Drepper, “a legend in the computer science world.” When she asked him about his view of current CS graduates, he said he worried that students were no longer focusing on the fundamentals. She asked him what he thought was the best CS curriculum. His response: to have a course taught in Scheme followed by fundamentals taught in C. This is exactly how CS is taught at Yale.

Similar to students today, when Balicki was in school, she did not think the fundamentals were that important. She said she wanted to see courses similar to the ones taught at other top-tier institutions taught at Yale.

“With time, my frustrations over this issue have faded as I’ve realized the value of my traditional CS education,” Balicki said. “I feel that my design choices are valued by my peers and superiors at work. My coworkers exchange ideas with me over what technologies they might adopt — they trust my opinion.”

Andrew Gu ’11, vice president of product at PaperG, which helps consumers with creative advertising campaigns, said that Yale CS prepared him well for his career. He said that he has found himself applying the core concepts he learned in CS classes at his jobs. Still, he added, Yale CS taught him nothing about web development or new frameworks, both of which he had to learn by himself.

“But Yale doesn’t teach you how to do finance or consulting either,” he pointed out. “If you take for granted that you want a liberal arts education, then taking that the classes you are given will not be the immediately practical thing.”

Brooks said he was glad not to have “wasted time in class” learning about web development.

According to Gensburg, who worked at Microsoft for two and a half years as a programmer for Excel, students at other schools spend years taking classes on how to program. But he said he was able to teach himself within a couple of days — sometimes within a single day — how to handle new languages. Although it was a little confusing at first, he “got the hang of it” because he was well-versed in the fundamentals.

Still, the majority of the 15 undergraduate students interviewed said they would like to see more courses that teach application-building. But they did concede that the small size of the current department makes it difficult to add more classes.

With six new professorships to be filled over the next several years, many students said they hope and expect to see more courses on applications and programming in the future.

But Francesca Slade ’10, who has worked at Google for the past five years and often conducts interviews for undergraduates, said that Google cares most about hiring graduates with strong CS fundamentals who are equipped to understand CS theory.

“Some schools, like Stanford, for example, take a myopic preprofessional view to the degree,” Slade said. “Stanford has a class for credit that all they do is cover how to do a technical interview.”

In contrast, Yale takes itself to be an academic institution across all fields, she said.

“That’s not a failing on their part.”

Yale may not teach students how to be programmers, she said, but, similarly to Gu, she pointed out that the University also does not teach students how to be lawyers or doctors.

FINDING A TECH NICHE

The paths available for students interested in tech careers are far-ranging, but, according to students and alumni, there are usually four main paths a tech student has coming right out of college besides graduate school. They can either choose to inhabit a larger, more established tech company like Google, join a medium-sized company like Dropbox, become a partner in a small-scale company or found their own startup.

Some students interviewed said that, in the same way big-name consulting and finance companies draw Yalies, larger tech corporations lure them with the promise of security and financial stability, while others said that Yale students do have the ambition and drive to create successful startups.

Daniel Kelly ’13 was the sixth employee to join Artivest, a startup founded by James Waldinger ’01 which uses technology to connect investors with leading private equity and hedge funds. He said he thinks many Yalies are “absolutely” risk-averse, and because of that, they often choose larger, more established companies instead of starting their own.

“[B]uilding a bigger startup culture at Yale will require students to become more comfortable with risk,” Kelly said. “Turning an idea into a business is a learning process that inherently has the chance of failure.”

Though Kelly sees Yale undergraduates as risk-averse, 75 percent of students and alumni interviewed who will be or are working at larger tech companies said their ultimate goal is to break off and either found their own startups, or work on the ground level of already existing ones. But as Michael Zhao ’15 pointed out, having that as one’s goal does not make it a reality.

“My biggest fear is going to LinkedIn and staying for way too long and not going into something more technical,” said Zhao. “I’m afraid of getting trapped in a vicious cycle and not having the guts to leave.”

Similarly, Giuffrida decided to start at Google although he did look into startups. He said he thinks it will be easier to found a startup after working at a larger company, developing his skills and saving up. The reverse scenario — in which someone moves from a failed start-up to a big tech company — is much harder to accomplish, he added. And when goes into the startup world, he wants to be taking the lead.

According to Ikenna Nzewi ’17, who works for the startup Huddlr, which uses geotechnology to facilitate social gatherings and was founded by two Yalies, part of the startup culture is being willing to jump full-force into something without knowing if it will work out. He said two of his employers have committed to the business full-time, and have no side projects or jobs besides building Huddlr.

“They want it,” he said.

STARTUP CULTURE

Abhijoy Mitra ’17 pulls out his phone and swipes through his app “BUBL” — pronounced bubble — to schedule an invite for a meeting. According to one of his partners Zachary Krumholz ’15, the app is meant to facilitate “spontaneous social gatherings.”

The team met at a Yale Entrepreneurial Institute-facilitated workshop. The third co-founder, Denis Aven ’16, said they are one of only a few groups on campus developing a mobile app startup. In comparison to schools like Stanford, where one computer science class’s final project consists of developing a mobile app, Yale does not have a market saturated with dozens of mobile app startups.

He said he thinks the gaps in the market could provide the group with a long-term advantage. But Yale has fewer resources than Stanford, which might create barriers to success, he added.

Although Krumholz is headed to work at Goldman Sachs in San Francisco next year and Aven will be interning at a financial advisory and asset management firm over the summer, Krumholz said they are still excited by the opportunity to work on a startup alongside other Yale students.

Ian Panchèvre ’15 is 25 years old, but he will be graduating from Yale this spring. After his sophomore year, he took a year off to work on a startup he had previously founded. The startup, Social Commerce, launched Qliq — a smartphone application that powered loyalty programs and provided mobile coupons for small business. He promised his parents he would only take a single gap year, but the business picked up momentum. Eventually, over 350 storefronts throughout South Texas joined Qliq’s merchant basis.

But the business started to struggle a few years later. Panchèvre shut it down in January 2013, just over two years after founding it.

Since then, Panchèvre has gone on to found two more businesses. His most recent business, Prepd, builds software for speech and debate teams to help students research, practice and compete. Just under 250 schools now utilize Prepd’s services.

He said he thinks YEI does offer some helpful advice and connections, but Yale’s support resources in no way compare to those at Stanford and Harvard.

Even 15 years ago, Yale barely had entrepreneurship on campus, Ryan said. The YEI fellowship was not created until 2007, but the past several years have shown a significant increase in support through the curriculum, he added

Kyle Jensen, director of entrepreneurial programs at the Yale School of Management, is responsible for crafting the University’s entrepreneurship curriculum, which includes roughly 10 courses open to all Yale students. Seven of these courses were created this year, “a very large expansion in opportunities for Yale students,” Jensen said in a Wednesday email.

The University’s entrepreneurial culture may be growing, but, according to Ryan, it does not get as much attention as the culture at other schools.

“We don’t get credit for Yale startups,” Ryan said, adding that Harvard gets credit for Facebook while Pinterest, which was founded by a Yalie, is rarely associated with the Yale name.

Reinking, who, like many CS majors, receives dozens of requests to join startups every semester, said that he believes this era in app development is a “gold rush.” But he thinks people have a “misguided” belief that all apps will be a success when, in reality, some of them “don’t even have a chance.”

Part of that, Reinking said, is because many of the apps at Yale are merely slight variations on an already well-established app — once they begin to gain popularity, the larger company will just incorporate the small app’s new feature, making it irrelevant.

Out of every 10 startups, it should be assumed that seven or eight will fail, Ryan said.

“The tech startup world is very competitive, which is good for the economy, but it can be hard for the individual businessman,” he added.

LOOKING AHEAD

Now that the Yale CS department has promised six new hires, Reinking said that, after weeks of promoting his petition, he can finally rest. Over 1,100 students, current Yale affiliates and alumni signed.

“The [faculty increase] did not come too late, but it couldn’t have come any later,” Reinking said. “That’s for sure.”

He thinks that Yale’s new joint course with Harvard, modeled after Harvard’s popular CS50 class, will promote a stronger programming culture on campus, which could increase the number of people participating in hackathons and startups.

Ryan said he wants to see the number of Yalies who graduate with a degree in CS increase from fewer than 40 to at least 75.

According to Ryan, five years ago the department was overly theoretical and not very “user friendly.” It lacked accessible introductory courses, which ended up discouraging a lot of students from taking computer science, he said. He thinks courses like CS50, which are fun and accessible, are needed in the department.

But even though the CS department is adding CS50 in response to student demand, he is unsure whether everyone at Yale understands the value of a strong Computer Science Department. But more people understand now including administrators and the Yale Corporation, he added.

“I’m feeling optimistic about what the university is doing, but we need to do more,” he said.

Of the 22 interns MongoDB hires every summer, two to three, on average, come from Yale, Ryan said. They are quality hires, he said, but “the missed opportunity is that we don’t have as many as we’d like.”

“We [hire] really talented people from Yale — we just need more of them.”

Correction: April 14

A previous version of this article did not include in its count of computer science majors in the class of 2014 students who double majored in computer science or completed a computer science joint major. The number of class of 2014 students who graduated with computer science as their sole major, one of two majors or part of their joint degree was 48.