As a graduate student at Harvard Medical School in the 1990s, Robert Means had his name on 18 publications. Currently, Means is a professor of pathology at the Yale School of Medicine, as well as director of graduate admissions for the microbiology program.

He has spent two decades in science. Now, Means said, he is leaving not only Yale, but science altogether.

At the end of June, Means’ contract with Yale will be up, largely because he was unable to bring in additional sources of funding to run his lab.

“I’ve still got projects going on that every day get me excited about science, but the rest of it — the managerial side of applying for grants that basically means life or death for your career — I have become so sullied by,” he said. “I’m going in a different direction because it doesn’t feel like, in this climate, that I can be intellectually free and still make a viable career out of it.”

What happened to Means at Yale is symptomatic of a national crisis in science funding, he said, particularly in biomedical research.

The National Institute of Health doubled its budget between 1998 and 2003, wrote graduate school dean Thomas Pollard in an article for Cell, leaving funding for biomedical research seeming relatively secure. But a combination of inflation since 2003 and a 5 percent cut in all NIH grant funding during the budget sequester of 2013 has left the current outlook for funding in the United States “grim.”

Yale has mechanisms in place to help support faculty struggling to secure research, but the University’s funds alone cannot insulate its researchers from the present climate. Government funding remains science researchers’ primary source of support, and those who lack it may find their labs in jeopardy.

Increasingly, researchers are looking for supplementary financial support from private foundations and corporate sponsors, many of which will underwrite research that investigates a specific disease or drug. Yet some worry this shift will leave basic science research, traditionally underwritten by public sources, by the wayside.

For all its impact on researchers, the greatest casualty of the funding climate may be the next generation of scientists.

“I feel that if we really want to keep an edge on creativity, we need to make it easier for people to enter the system and fund it at a greater level than we are right now,” said genetics professor Arthur Horwich. “We’re scaring people away.”

THINGS FALL APART

The funding climate has left all researchers, even the most well-established, feeling its effects.

“Everyone is in the same life raft, and they all have little holes in them, and they’re sinking,” said Richard Sutton, a professor of medicine at the Yale School of Medicine.

Of the 20 grants neurobiology professor Amy Arnsten wrote in the past two years, just two were funded. Arnsten said she sometimes made it to the finals of an application round, only to be turned down after months of work.

Arnsten said the NIH Pioneer Award of $2.5 million over five years that she won in 2013, although prestigious, provides less financial support than she would have received from the NIH Program Grant her lab was recently unable to renew. Faced with a decrease in funding, Arnsten said her lab has had to downsize.

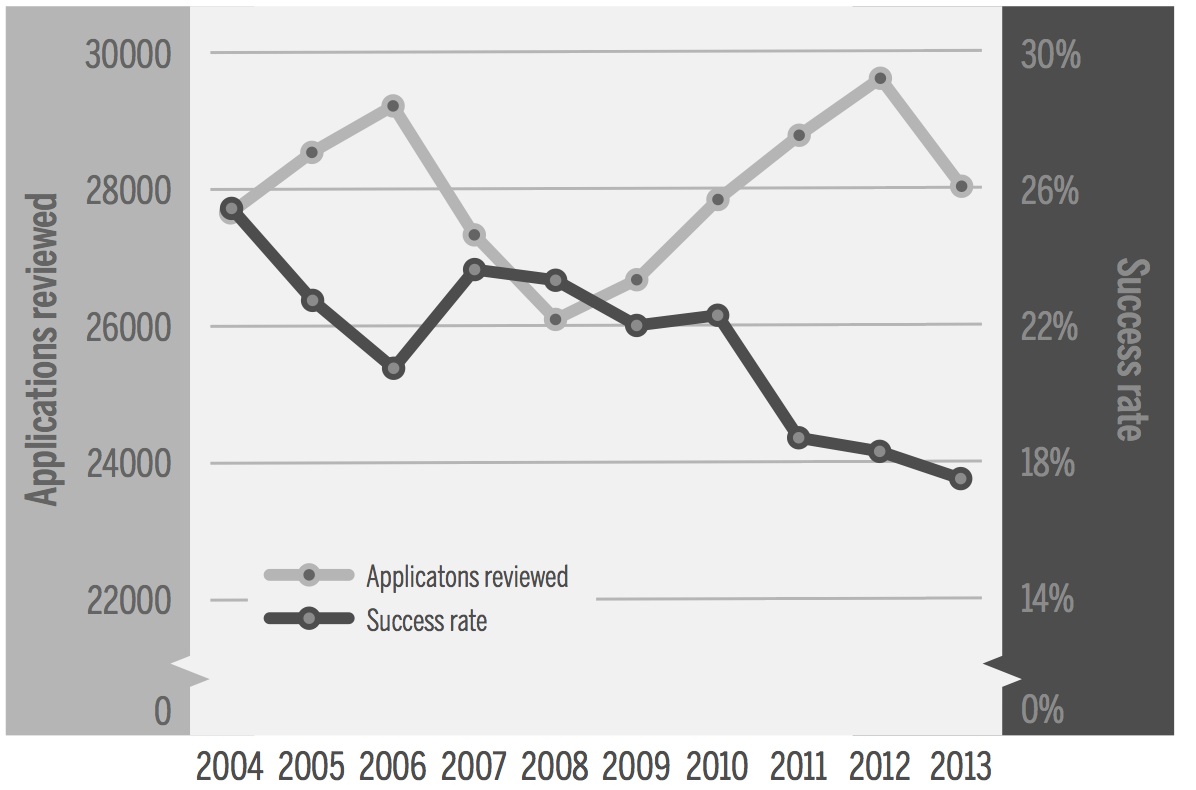

In 2012, the number of applications filed for an NIH RO1 Equivalent grant, the oldest and most common type of research award, was 29,626 — the highest in nearly 30 years. The success rate for that grant was 30.7 percent 10 years prior; in 2012, it was 18.3 percent. Last year, the rate fell to an all-time low of 17.5 percent.

Faculty at the Yale School of Medicine said they have experienced changes in the funding climate more acutely than their peers at Yale College.

At the College, faculty receive nine months of their salary from the University, and are expected to raise their remaining three months of salary through grants. In contrast, most researchers at the Yale Medical School need to raise a majority of their salary through grants.

Yale biology professor Paul Forscher called his recent search for funding a “harrowing” experience. He said he felt lucky that he was able to resolve his lab’s funding challenges and noted that a number of his colleagues had been much less fortunate despite their research qualifications.

According to bioengineering professor Stuart Campbell, for a grant application to stand a chance in competition today, it has to be “basically perfect” — as much a product of good ideas as of how well those ideas are articulated.

Even excellent grants have no guarantee of receiving an award, said Richard Sutton, an internal medicine professor at the Yale School of Medicine. When so many researchers of comparable prowess are applying for grants, he said the selection process has assumed a degree of arbitrariness: Receiving funding for one grant over another can come down to something merely “nitpicky.”

“Some people will say it’s turned into a lottery, and ask ‘Why do we bother?’” Campbell said. “But I guess I’m an incurable optimist. It’s pretty amazing that our society will support scientists and invest in research. To be able to spend a couple months writing a document, doing some preliminary experiments, and then receive 100,000 dollars in return seems like a pretty good return on your investment.”

But Campbell, along with other faculty members interviewed, acknowledged that the funding climate has left him under significant stress.

Increased competition for grants means more time spent writing and refining grant applications and less time doing research, said Valentina Greco, a genetics and dermatology professor at the Yale School of Medicine. She and other researchers interviewed noted that pressure to find funding has left them struggling to balance keeping their labs financially afloat with training and mentoring their lab personnel.

Campbell, who arrived at Yale a year and a half ago, said he often hears his older colleagues talking about “the good old days” of NIH funding. Horwich, who opened his lab in the 1980s, recalled a past when things were easier.

“I had NIH support within a few months of submitting my first grant, and think it’s very unlikely that anybody would have that luxury,” he said. “I think few people would even think to submit an NIH grant in their first month or two. We’re in a completely different era now.”

TURNING TO YALE

In researchers’ times of need, the University has made efforts to step in.

Forscher was able to maintain his lab through Yale’s bridge funding — money allocated to support researchers who are in between sources of funding until they are able to secure more. Pathology professor Means said he also received generous bridge funding from his department after he lost grants that paid for his salary and one graduate student at a reduced salary. Still, Means said he was unable to secure the necessary government support to keep his lab running.

Deputy provost for science and technology Steven Girvin said the provost’s office has received more requests for bridge funding as of late. But because the University’s ability to provide for bridge funding is limited, and the University is still in the process of balancing its budget, the office can only fund so many requests, he said.

Support is still ample for incoming junior faculty members, who praised Yale’s start-up package for new hires in the sciences. The package, which varies by department, gives researchers seed money to jumpstart their research, buy equipment and hire lab personnel. To attract the sought-after researchers in the country, Girvin said, Yale must offer rates competitive with its peer institutions.

Horwich said departments are aware that substantial start-up packages are critical for attracting new hires, particularly in today’s funding climate. He added that because it may take even the most talented budding researchers years for their labs become competitive when applying for grants, the University recognizes a need to support them as they open their labs and start acquiring results.

Despite increased competition in the grant application process, Horwich said researchers at Yale have remained committed to helping their peers succeed. A month before they submit any major proposal, junior faculty in the genetics department first submit their applications to their other department members, who will review the proposal as if they were reviewing it for a grant.

“I think it’s a very supportive and collaborative atmosphere, where we really make sure everyone’s able to make the grade,” Horwich said. “I think the tenor of most departments is, if we’re bringing someone in, we really want to see them succeed, and we’ll extend a helping hand at every level.”

Within their labs, Greco said, researchers are coming up with creative approaches to cope with a lack of funds. She has designed cost-effective projects that allow personnel to share equipment and other supplies.

Sharing at Yale also happens on a broader scale. The University is home to a number of core facilities, like the Center for Genome Analysis on West Campus, that faculty share to save themselves the full cost of buying expensive equipment on their own.

Occasionally, a researcher challenged for funds will need to downsize. Downsizing might not necessarily be a bad thing, Forscher said, because fewer lab personnel means that there will be more of the primary investigator’s attention to go around. Smaller labs, he added, might also have the potential to result in more forward-thinking research ventures.

But, Greco said, creativity can only last a researcher so long.

“When you don’t have a lot of money, it can allow you to focus and be more productive,” she said. “But the level [of funding] now is inhibiting great scientists from performing as they could.”

WITH PRIVATE SCIENCE, A QUESTION OF MOTIVES

With federal funding on the decline, and Yale unable to bear the brunt of its researchers’ full financial needs, researchers are expanding their search for alternative sources of support.

“Everyone is worried,” Sutton said. “You apply for grants that you wouldn’t even think about applying for. You apply all over the map. If you throw something at the wall, something is bound to stick.”

Increasingly, private foundations are gaining prominence as a source of research funding. Even in the 1990s, private agencies already played an important role in filling the funding gap between the postdoctoral fellowship and beginning faculty salary, said Flora Vaccarino, a neurobiology professor at the medical school. As a postdoc, Vaccarino received funding from the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression, which allowed her to hire a graduate student and buy supplies for her investigations.

Foundations tend to fund riskier research than will the government, she said, and to focus less on the technical details of the application and more on the applicant’s aspirations and goals for their studies. Private grants, she added, also provide trainees with a independence to fund research outside the terms of their mentor’s grant.

Over the years, Vaccarino said, more researchers, herself included, have begun applying their research to areas that are more likely to receive funding from private organizations, with autism as a prime example. As autism rates have climbed, so has the number of organizations interested in supporting neuroscientists addressing autism’s causes and possible therapies, she said.

In search of funds, Greco said she has applied her interest in cancer pathology towards researching cancer treatment, where foundation support is also on the uptick.

“I think it’s very important to study cancer, but my heart is passionate about how it just works,” she said. “If I had the money, I would probably only do that. I don’t regret [my research], but if I could just follow my passion, that would be better.”

Private funding is more a complement than a substitute for federal funding, as foundations tend to not only provide less money but also fund fewer researchers overall, according to professor of biomedical engineering Tarek Fahmy.

At Yale, Arthur Horwich is one of 19 Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) Investigators, who receive long-term private funding from the Howard Hughes Medical Foundation to cover their research, personnel and equipment costs for five-year terms. Compared with the over 300,000 researchers who receive NIH funding, however, the current 332 HHMI Investigators number relatively few. The HHMI application process is also highly selective — in 2013, only 27 Investigators were selected from an application pool of 1,155, an acceptance rate of just over two percent.

Arnsten receives private funding from the Kavli Foundation, which under the late Fred Kavli established the Kavli Institute for Neuroscience at the Yale School of Medicine in 2004. Although she is grateful for the support, she said, the money only amounts to a “safety net.”

“Private funding is absolutely not the answer,” Arnsten said. “It’s a truly symbolic drop in the bucket.”

GOING CORPORATE

Patricia Pedersen, director of the Office of University Corporate and Foundation Relations, said her office’s role in attracting and managing corporate investment for science research has expanded with the 10-year decline in federal funding.

“The great news is, our faculty are brilliant and talented, but even they are not immune,” Pedersen said. “You can’t do science on your own. They’re letting us know on a daily basis that we need to raise support.”

One way that researchers have found funding is by partnering with pharmaceutical companies to research and develop new drugs, said biomedical engineering professor Tarek Fahmy. Part of Fahmy’s lab is funded through Pfizer, and many of his colleagues have lately interacted with companies to fund their own research for disease therapies.

Yale has formed two significant corporate partnerships in recent years. In 2011, the Yale School of Medicine began a collaboration with biopharmaceutical company Gilead Sciences, Inc., which will give the University $40 million towards research on novel cancer therapies. Last year, the medical school began a research partnership with global pharmaceutical company Abbvie, which will award $14.5 million total in funding to School of Medicine faculty in the Department of Immunobiology. Girvin said the success of these two partnerships suggests Yale will have other opportunities for corporate sponsorship in the future.

The University’s relationship with corporate sponsors came under fire in 2010 when the university accepted funding from PepsiCo for a $250,000 graduate fellowship in nutritional science at the School of Medicine. Yale alumni interviewed in the New York Times expressed suspicion that the partnership would lead to corporate interference in the course of research.

In an interview with Yale Alumni Magazine, however, Levin stated that the company had no influence over the candidates chosen to receive the fellowship.

Pedersen said that the donation was no more than “outright philanthropy,” adding that her office is extremely sensitive to concerns about corporate investment driving academic agenda. The University also convenes faculty committees to ensure they have the final say on how corporate money is used.

“For any interaction involving an outside company, all the t’s are crossed and the i’s are dotted,” Fahmy said. “There’s nothing that would present a liability.”

Researchers interviewed said the growing presence of private foundation and corporate funding is not legally problematic, but might carry negative implications still. Many researchers expressed concern that research that translates into practical benefits like disease therapies, or translational research, is beginning to take precedence over basic research, which aims to improve scientific understanding without an end goal in mind.

Private foundations often support research on certain diseases with which the foundation’s family members have been afflicted, Arnsten said. And even the NIH, which has a history of providing funds for basic science, seems to be feeling pressure to shift their funding in the direction of translational research, Horwich said.

In 2012, the NIH opened the multi-million dollar National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences to further research in drug development. Asked by a House of Representatives panel if the center would draw funds away from basic research, NIH director Frances Collins said he did not expect the present level of basic science funding to change.

But the center’s development prompted concern from biomedical researchers across the country in Forbes and Science Magazine about what the decision signifies for the future of basic science support.

“Sure, you can start off working right smack on the disease, and sometimes you’ll make an advance,” said Joel Rosenbaum, a professor of molecular, cellular and developmental biology. “But most of our medical benefits have come from advances in science where the scientist had no idea that his research would lead in that direction.”

THE NEXT GENERATION

“I advise my students not to stay in the United States.”

Such was the counsel of Yale professor James Rothman, winner of the 2013 Nobel Prize in Medicine, to prospective biomedical researchers at a panel discussion about declining federal funds for science research in Washington, D.C. last year.

Like many senior biology majors interviewed, Shivani Bhatt ’13 MED ’21 said she had not considered her future chances at grant funding when thinking about postgraduate applications. She added that she applied to Yale’s M.D./Ph.D. program, undecided about which career path, researcher or doctor, she wanted to pursue.

“But when I heard my postdoc friends who are getting straight Ph.D.s talking about how competitive [funding] is, I started thinking it’s maybe not so bad that I’ll have the extra degree,” she said.

Linda Zhou ’14, a molecular biophysics and biochemistry major who will enroll in an M.D./Ph.D. program next year, also noted the security that the “MD” portion of the program affords. She added that she has observed her peers thinking more critically about whether or not to attend graduate school directly after college and looking to explore other fields, like life sciences consulting, before beginning the next phase of their education.

An MB&B major with plans with plans for graduate school, Victor Kang ’14 said he will work for a biopharmaceutical consulting firm upon graduation. Kang said graduate schools are looking for students who are not only scientifically skilled, but also demonstrate leadership and team-building skills that he hopes to develop by working in business.

MB&B major Megan Jenkins ’14, who will be in China for the next two years on a fellowship teaching English, said she is still unsure about whether she will head to medical school or graduate school in the future.

“Working in a lab has given me the opportunity to see the unglamorous side of research, like finding funding and the dark side of job prospects,” Jenkins said. “Right now I’m trying to evaluate whether it’s worth it for me to go down that road.”

Jenkins said that many students new to research may be unaware of how difficult the scientific process can sometimes be, adding that she would encourage interested students to join labs early on to determine if research truly lies within their interests.

Elisa Visher ’14 said she also plans to take time off before enrolling in graduate school. Of 25 senior biology majors contacted, only Visher said she wants to pursue a career in academia.

“I don’t think it’s going to be a stable career, [and] I think it’s a precarious situation,” she said. “But somebody’s got to do it, and I might as well try. Life isn’t risk-averse, and sometimes you have to take the risk.”

CHANGING TIDES

Science research is no stranger to funding challenges, Girvin said.

“I’ve seen worse times,” he said. “These things do go in circles. Which is bad, because you can’t turn the research spigot on and off and hope people will appear every time there’s more money. You need a steady, predictable budget for this.”

Forscher and other researchers speculated that it might be years or decades before funding levels return to where they once were.

He added that the paradigm of how science is conducted in academia could be about to shift. With NIH funding on the decline, he said, the balance between public and private funding may be tipping towards private.

“Perhaps, right now, we’re in a moment in history where the paradigm of how science is done in academia is changing,” Forscher said. “It’s possible that we’re just going to have to get used to a more restricted funding environment.”

Campbell, for one, said he is counting on things to improve.

“I guess I’m not big into hand wringing,” he said. “I’m just trying to do the best I can.”